According to an eye-popping report in the US-based Time magazine (June 9), in 2001 the total number of passenger cars in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was 10 million. In 2024, the number of cars manufactured annually in PRC has risen to 27.4 million. Currently, PRC is the world’s largest exporter of passenger cars, with 4.9 million per year sold around the world. In new genre EVs (electric vehicles), the country’s domestic sales aggregate 66 percent of global sales. In the quarter January-March 2025, BYD, China’s giant EVs manufacturer, produced 416,388 electric cars (more than Tesla).

Now China is using its primacy in the EVs manufacturing business as a base to emerge as global leader in generative AI, quantum computing and humanoid robotics. Last year, 190,000 robotics companies were registered in PRC and this industry’s output is budgeted at $43 billion (Rs.370,870 crore) by 2035. Meanwhile the number of AI-related cited research papers of PRC last year were 2x of USA. “We believe the Chinese market has the best talent. Every year, there are several million science and technology graduates,” who serve China Inc well, William Li, CEO of NIO Inc, Shanghai, PRC’s top EV batteries manufacturer, told Time.

It’s pertinent to note that in sharp contrast with India Inc, business and industry leaders in China repose great confidence in their universities to churn out highly qualified and readily employable graduates. Nor is this admiration for higher education institutions only within China. In the latest Times Higher Education 2025 global ranking of universities, seven Chinese universities are ranked among the Top 100, and two among the Top 50. On the other hand, India’s top-ranked university is Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru numbered in the 251-300 band.

Hardly surprising. Instead of being granted full autonomy and freedom to joyfully experiment, generate new knowledge and ideate path-breaking technologies, India’s 47,000 colleges and 1,168 universities are subject to tight regulation by the anachronistic UGC (University Grants Commission). And although the new National Education Policy 2020 recommends gradual autonomy for all HEIs, it contradictorily mandates the establishment of over a dozen government committees (SSA, SSRA, HECI, NAS, UGC and AICTE) to supervise and regulate schools and HEIs.

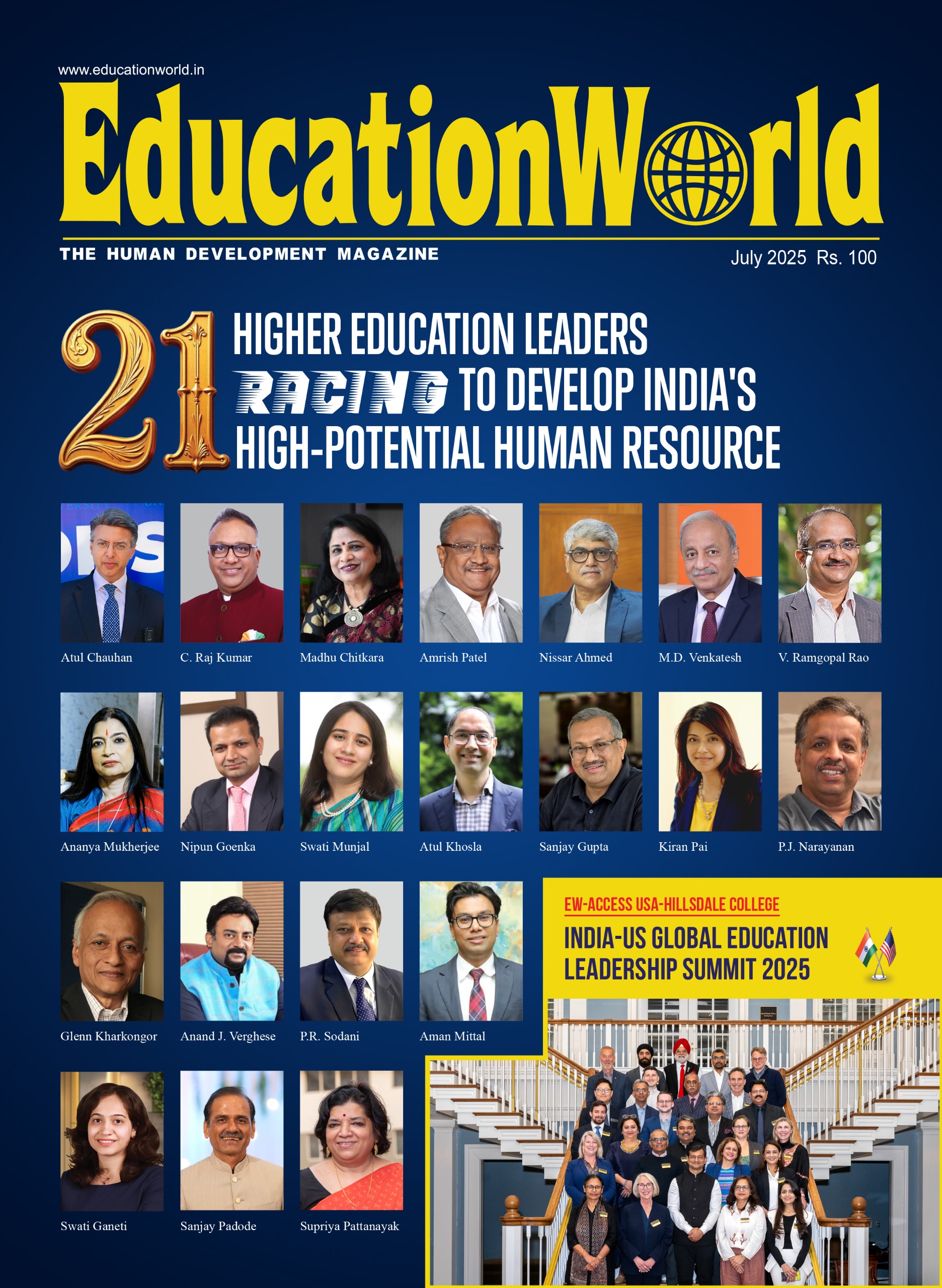

Yet perhaps all is not lost. Belatedly a new generation of highly learned, visionary, go-getting and unsung privately-promoted higher education leaders — Chancellors, Vice Chancellors, Presidents, Deans — have shed traditional diffidence and are providing industry-aligned, research and innovation-driven education to a large and multiplying number of youth countrywide.

For the past seven decades, the Academy has been a passive observer of post-independence India’s disappointing national development effort. Now it’s high time that academics become actively involved — perhaps lead — the race towards Viksit Bharat and attaining the $30 trillion GDP target set for 2047.