Haigui at work: falling RoI

It has been a difficult summer for Chinese students in America. On May 28, the State Department announced a campaign to “aggressively” start revoking their visas. One of the targets will be Chinese students in “critical fields”, science and engineering programmes that are deemed to be of strategic interest to China. Another will be students who have unspecified “connections” to the Communist Party. For young people in China thinking about where to study, America now looks a dicey proposition.

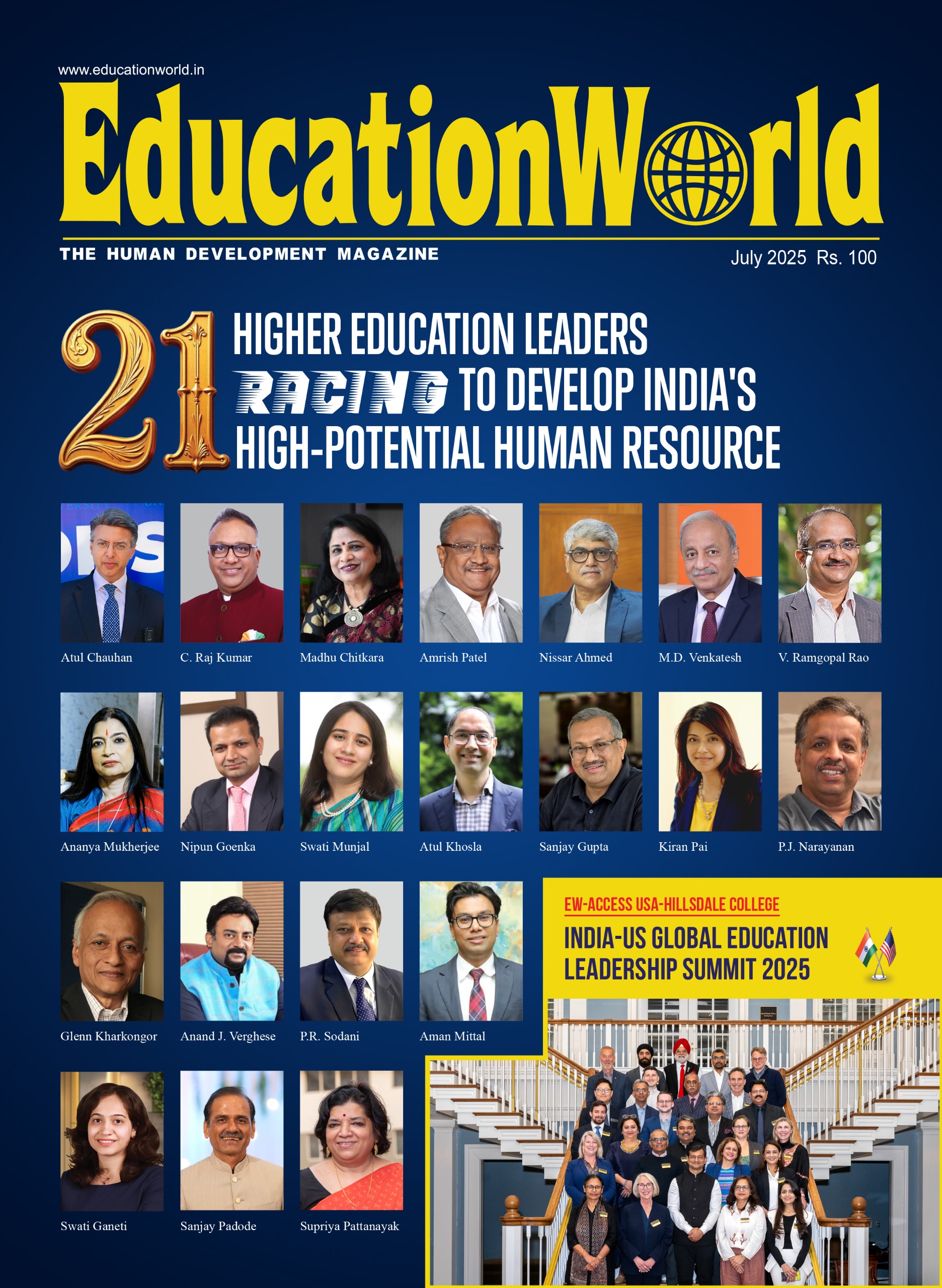

Since China opened up in the late 1970s, some 3 million young Chinese have gone to study in America. Many have settled there. Others have come back, typically to pick up a fancy job. They are known as haigui (sea turtles), a homophone for “returning from across the sea”. America’s Ivy League became something of a finishing school for the children of the well-heeled in Beijing and Shanghai. President Xi Jinping’s daughter was an undergraduate at Harvard. Mid-career party officials have also gone to America to learn about modern governance.

But for many Chinese, the perceived return on investment of an American education has been falling. It has always been expensive, and these days middle-class families are less willing to shell out amid an economic downturn and a slump in the property market. They can choose cheaper universities in Britain, for instance, which in the academic year 2023-24 hosted nearly 150,000 Chinese students. Of late, more have been going to Hong Kong, Singapore and elsewhere in Asia. Classes are often taught in English, and they are seen as friendlier places to study. The number of Chinese students in Japan increased to 115,000 in 2023 from under 100,000 in 2019.

Like many young Chinese these days, Lei, an economics undergraduate, dreams of finding a stable position at home after graduation, in the Chinese government or in a state-owned company. Such employers now are often suspicious of graduates with a foreign education, he says. In April, Dong Mingzhu, chairwoman of Gree Electric, a large appliance manufacturer, said her company did not hire haigui in case they had been recruited as spies by foreigners.

Meanwhile China’s own top universities are increasingly competitive and attractive, especially in fields such as science and engineering. “China can catch up with and even surpass America,” reckons one biology Ph D student at the elite Tsinghua University in Beijing (ranked #20 worldwide by the QS World University Rankings; Peking University, next door, is ranked #14). “It just needs a bit more time.” Just look at his own professors, he says. The older ones all have degrees from American universities. The younger ones were typically educated in China.

Many students at home don’t seem too dismayed by America’s new visa policies. Li, a Masters student researching satellite propulsion at Beihang University in Beijing, says he can understand why America does not want to let Chinese citizens into its high-tech programmes (Beihang graduates have been banned from studying in America since 2020 because of the university’s close links to China’s armed forces). But he sees a silver lining. “People who can go study overseas tend to be pretty impressive. So if they stay, it will help domestic research and development,” he says.