Autar Nehru (Delhi)

NEP 2020 formally released five years ago: uncelebrated milestone

For academia, july 29 is — or should be — an important milestone. It marks completion of five years since the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 was officially approved and promulgated by the BJP/NDA government at the Centre. However very few, if any in academia are celebrating this milestone anniversary.

For a start, NEP implementation has been dealt a heavy blow with the prolonged illness and passing in April, of space scientist Dr. K. Kasturirangan, whose 484-page report to modernise India’s moribund education system was translated into the 66-page NEP 2020. Under his leadership, the National Curriculum Framework (NCF) for Foundational Stage was released in October 2022 and NCF for School Education in 2023. But since then, there’s been no word on the pending NCF for Teacher Education and NCF for Adult Education.

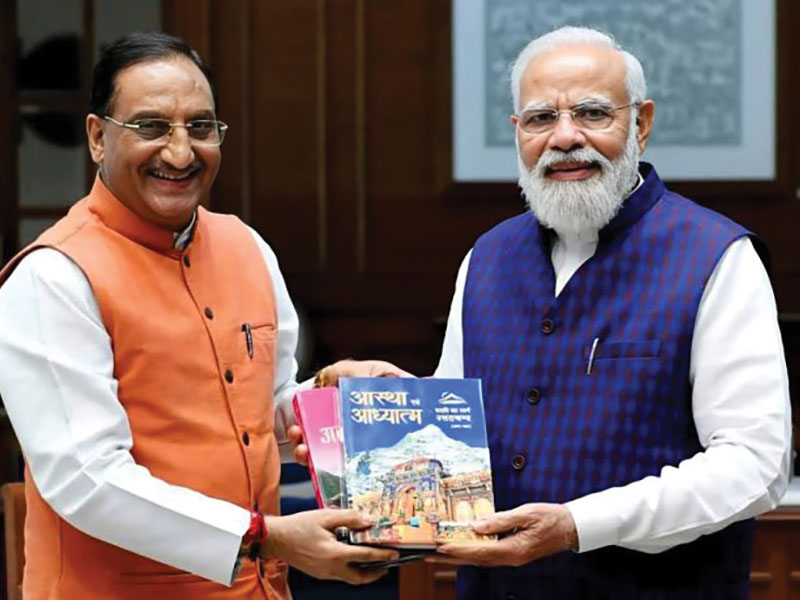

Nevertheless in a media blitzkrieg to mark completion of the BJP/NDA government’s 11 years in office at the Centre, the government published a booklet titled Viksit Bharat ka Amrit Kaal — 11 Saal last month. In this publication, the government claims that several reforms recommended by NEP 2020 have been successfully implemented, viz, early childhood education has been made compulsory for all children from three years of age, and integrated with primary education; school enrolment has increased to almost 100 percent with school dropout rates reducing; inter-disciplinary education in higher education has become a reality and employability has been enhanced through several skills-based vocational learning programmes.

Yet the latest Annual Status of Education Report published by the highly respected Pratham Education Foundation indicates that learning outcomes in India’s rural schools are stagnant. Likewise industry reports that the great majority of 10 million graduates certified by India’s colleges and universities annually are not sufficiently qualified for employment commensurate with their qualifications. Although there is a flurry of activity in the education sector, there is little evidence of reforms-driven forward movement.

An especially ill-advised provision of NEP 2020 is resurrection of the ghost of the three-language prescription for all children in primary-secondary education. This mandate requires all children to learn three languages, viz, their mother tongue, a “foreign language” (English) and Hindi. This mandate of the K’Rangan Committee and NEP 2020 was particularly ill-considered because when Hindi was declared the national language in 1965, riots broke out in southern India protesting “Hindi imperialism” and imposition of this lingua franca of the northern states countrywide.

At that time, it was resolved that English, a “neutral language” for all Indians would remain the associate national language, language of the upper judiciary and the medium of communication between the states of the Indian Union. Ill-advisedly following the advice of the K’Rangan Committee, NEP reiterates adoption of the three language formula for all children.

The outcome of this history agnostic mandate of NEP 2020 is that several states of peninsular India, in particular Tamil Nadu and Kerala, have rejected NEP 2020 in toto. Tamil Nadu has already drawn up its alternative SEP (State Education Policy) arguing that since education is a ‘concurrent’ jurisdiction subject under the Constitution, it is entitled to draw up its own independent SEP. Karnataka and Kerala have followed suit while several other states including West Bengal and Chhattisgarh are mulling this proposition.

Indeed five years on, the initial hosannas and acclamation that greeted NEP 2020 are increasingly turning into disillusionment. Prof. Santosh Mehrotra, former professor of economics at India’s show-piece Jawaharlal Nehru University who currently teaches the subject at Bath University (UK), is of the opinion that NEP 2020 does not “reflect the ground realities of Indian education”. “There is no serious recognition of the systemic crisis that unfolded after massification of school education. While enrolment surged, especially after the free mid-day meal scheme was launched and incentives like free bicycles for girls were introduced in Bihar, learning outcomes remained stagnant. The unemployment crisis in the country is directly correlated to this education trajectory of the past three decades. There is no awareness of this in government and NEP 2020, glosses over this foundational issue,” says Mehrotra.

Other critics are inclined to be harsher. Writing in the Chennai-based daily, The Hindu (May 14), Bengaluru-based professors Gautam Desiraju and Mirle Surappa at the Indian Institute of Science and National Institute of Advanced Studies respectively, describe NEP 2020 as a “dead fish in the water”.

According to them, the high rate of educated unemployment at 42 percent indicates that “NEP is outdated and financially unviable in the India of 2025”. “Lip service is paid to new ideas such as Indian knowledge systems, mother tongue learning, changing history textbooks, flexible curricula (but there is) complete absence of methodology to effect its recommendations…”

Against this darkening backdrop, it’s noteworthy that in terms of its aims, objectives and prescriptions, NEP 2020 bears uncanny resemblance to its predecessor NEP 1986 which it is painfully clear, had no success in halting the downward slide of Indian education. There’s similar prospect of NEP 2020, noble in intent, but prescribing more of the same, suffering the same fate.

In the circumstances, perhaps the best option for government is to ignore the numerous supervisory control-and-command mandates of NEP 2020 and expedite its recommendation to confer autonomy to education institutions across the spectrum. History of the past lost decades has provided ample proof — by way of sub-standard learning outcomes in India’s schools, colleges and universities — that top-down control and micro-management doesn’t work. The best available option is to leave academics and human resource development to academics.

Also Read: Delhi DoE invites online transfer applications from teachers