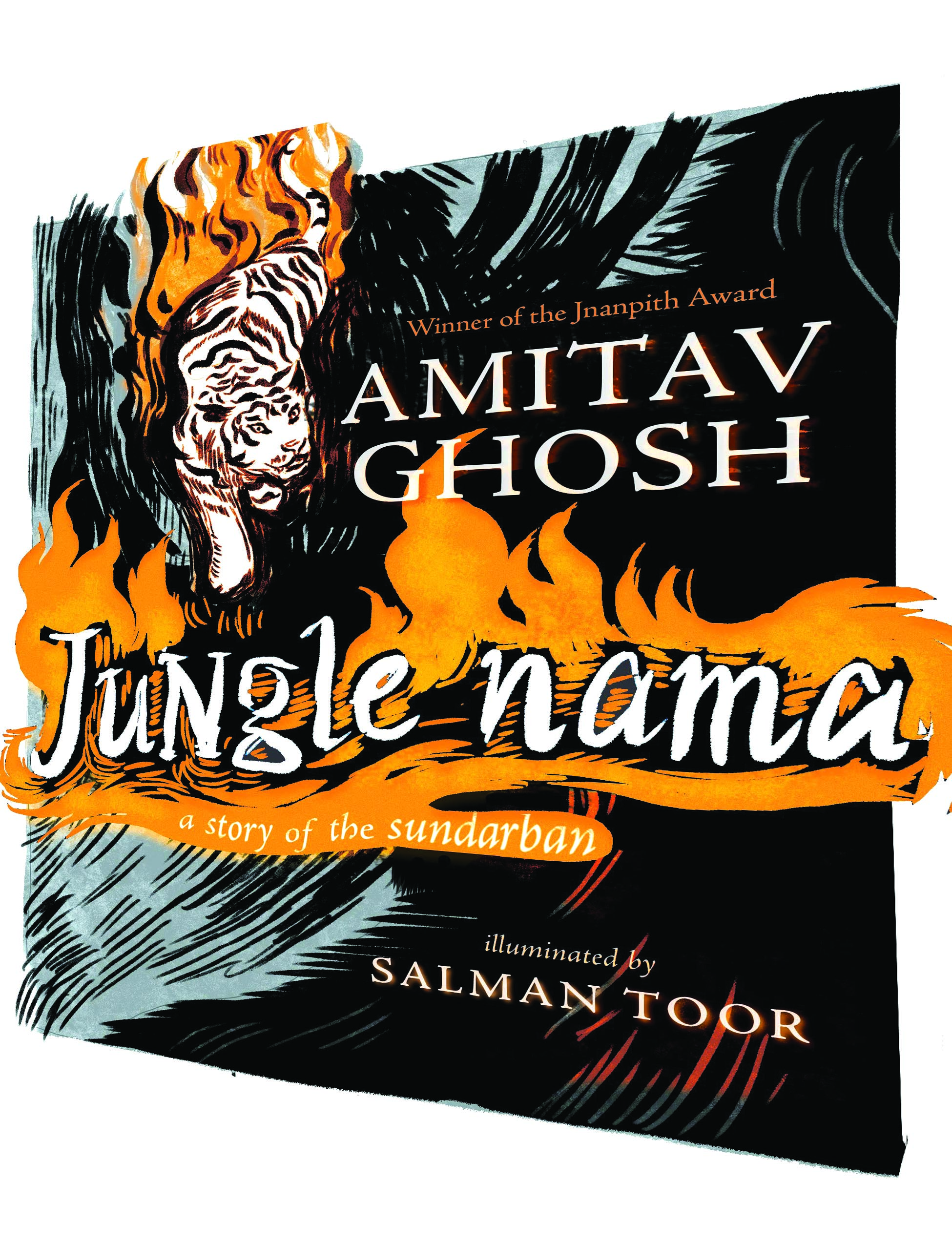

Jungle Nama: A story of the Sundarban

Amitav Ghosh

Harper Collins

Rs.699; Pages 79

Jayati Gupta (The Book Review)

Following his two widely acclaimed fiction novels The Hungry Tide (2004) and Gun Island (2019), in Jungle Nama (2021), Amitav Ghosh revisits the Sundarbans, the “tangled green archipelago” of riverine Bengal.

Ghosh’s first book written in narrative verse is rooted in the mythical tale of Bon Bibi ‘Mistress of the Forest’; Shah Jongoli, her muscle-man brother; Dokkhin Rai, the demon King in the avatar of a tiger; Dhona, a greedy trader and Dukhey, the poor victim symbolic of the common man.

In the preface Ghosh admits that the objective of his latest oeuvre is to express his grave concern about the dangers posed by climate change and despoliation of the ecology and environment through the oral tradition of folk tales passed down from one generation to another. These tales survive through live staged performances with local variations while retaining their imaginative core themes.

The epic proportions of the Bon Bibi Johurnama were documented in print in the late 19th century. Ghosh retrieves one episodic plot from the vernacular version and transcreates it, converting the verbal text into an English verse narrative with illuminating illustrations. The author is convinced that in this era of derangement and the Anthropocene, this book seriously engages with understanding the human predicament.

Written as an allegory, the narrative verse is focused on line-in-sand boundaries drawn between human and animal realms in the Sunderbans after the arrival from Arabia of Bon Bibi, personifying compassion, and Shah Jongoli, an embodiment of power and strength. Their arrival ends the oppressive rule of Dokkhin Rai, who preyed on humans in guise of a tiger with “stripes, which danced like the flames of a fire”. By demarcating spaces and enacting laws against transgression, the new dispensation ensured that “every creature had a place, every want was met/all needs were balanced, like lines of a couplet.” In contemporary ecological parlance this translates as respecting biodiversity and ensuring environment sustainability.

Embedded in this jungle lore is the story of Dhona and Dukhey, the former personifying wealth and the latter poverty. They re-enact the eternal saga of human greed, exploitation of nature and mass deprivation at the bottom of the socio-economic pyramid. The acquisitive Dhona lacks “life’s most splendid gift” of contentment and embarks on a life of thievery. “It’s springtime now and the mangroves are filled with hives. Let’s try to collect the richest hoard of our lives,” he exults. Preserving and sustaining the natural environment by practicing needs-based resources mining cuts no ice with Dhona.

The dramatic plot-line of the mythical narrative with its components of adventure and anxiety, danger and fear, magic, dreams and fantasy unfolds in the depths of the forest as Dokkhin Rai arouses primal instincts that succumb to temptation. A power game played out on unequal ground.

“You were caught in my coils when you entered this raj,” growls the demon as he bargains for human flesh and blood. Salman Toor’s illuminations are evocative of the dark jungle, dense forest greenery and peepul tree that almost swallow Dukhey, the unsuspecting bait and victim.

Dukhey’s appeal to Bon Bibi for succour, her instructions to Shah Jongoli to capture the predatory Dokkhin Rai alive, Dukhey’s surrender to the mistress of the forest and his reverence for his saviour, complete the legend of this regional folk deity of the tide country. Importantly, the deity combines Hindu and Islamic characteristics that belong to a folk pantheon, regionalised and localised but believed to be alive and potent even in contemporary times.

The decrees issued by Bon Bibi are basic, universally accepted tenets of environmental balance, protection of habitat and biodiversity and limiting human greed. The rationale of the book remains a single-minded intent of reiterating these values “for this era of planetary crisis”.

The author’s experiment with a new literary form, incorporation of visual images and adaptation of the vernacular poyar meter into 12 syllabled lines and 24 syllabled couplets, sends a strong message of the importance of replicating literature and story-telling to preserve the literary and cultural legacy of ancient times.

This book bears a compelling message for our times and Amitav Ghosh is unabashed in claiming that the folktale is “founded on a better understanding of the human predicament”. This saga of southern Bengal is hybridised by the influx of Arabic characters, Persian vocabulary and Quranic Arabic. By incorporating them in this adaptation of linguistic peculiarity, Ghosh reinforces the multicultural versatility of the English language he uses. Jungle Nama is an Indian folk tale for a contemporary, global readership that’s interested in preserving Planet Earth and its resources for future generations.

Also Read: Malaysian Ramayana