Private School Fees: Beware government regulation trojan horse

Collective bargaining by school-specific parents associations is a better option than inviting government fees regulation. India’s weak national development experience proves that inviting government intervention is to invite a sea of troubles – Dilip Thakore

Parents protesting private school fee increases countrywide: continuous agitation & litigation

Education of India’s 260 million child population simultaneously represents a national priority and business opportunity. Yet because of muddled policy formulation, neither of these socially beneficial imperatives are being realised. Learning outcomes of 150 million children in 1 million government schools are rock bottom, and managements of 450,000 private schools which host an estimated 110 million children are harassed by continuous (state) government education ministry bureaucrats, inspectors and also middle class parents on the issue of school fees.

On April 29, shortly after the BJP/NDA coalition swept the Delhi state legislative election ending the two-term incumbency of the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), the new government headed by chief minister Rekha Gupta approved a draft Delhi School Education (Transparency in Fixation and Regulation of Fees) Bill, 2025. The Bill proposes establishment of a three-tier structure — school-specific fees committees, district fee appellate committees and revision committees — to approve and regulate private school fees and address parents’ grievances.

Although the draft has not been made public at time of writing, according to reliable sources, the all-important school-specific committee will comprise six school representatives (including principal and three teachers), five parents/guardians (selected by draw, with representation for women and reserved categories), and a nominee of the DoE (Department of Education). The Bill details specific parameters for fees determination, including the school’s location, infrastructure, education standard, operating expenses, and surplus revenue. Schools charging more than the fees set by the school-specific committee will be liable to penalties ranging from Rs.1-10 lakh. The draft Bill also prohibits coercive action against students — such as expulsion or withholding results — for non-payment of fees.

However even as the new Bill is pending debate and enactment in the Delhi state legislative assembly, on May 9, the Delhi Public School (DPS), Dwarka (Delhi), expelled 32 students for non-payment of tuition fees. Last July (2024) when the school — promoted by the DPS Society (estb.1949) which manages a chain of 231 owned and franchised DPS schools in India and abroad — increased its fee by a reported 36 percent, the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) filed a criminal case against DPS, Dwarka under several provisions of the Juvenile Justice Act, 2015. Even as investigations were being conducted, with the new academic year scheduled to begin in July, the DPS management expelled 32 students for non-payment of contracted fees for almost a year. This prompted parents of the students to file for a stay order on the ground that the management was engaged in “profiteering” from education.

With counsel for the school contending that DPS, Dwarka has run up an accumulated debt of Rs.31 crore during the past decade and that parents of the 32 expelled students owed Rs.42 lakh by way of fee arrears, on May 19, Justice Sachin Datta of the Delhi high court reserved his verdict on the issue of expulsion of the students for non-payment of contracted fees.

Similar litigation against private schools for levying ‘exorbitant’ tuition and related fees is pending in courts across the country. In Uttar Pradesh, a committee appointed by the Supreme Court is investigating the financial condition of private schools that allegedly charged “excessive” fees during the Covid-19 pandemic when school campuses were shut down and teaching-learning went online. In Madhya Pradesh, the high court has granted interim relief to private schools which have been ordered to refund fees collected in violation of 2017 fee regulation rules stipulated by the state government. In Telangana, the high court has issued notices to the Central and state governments following admission of a writ petition protesting high private school fees; in Gujarat, 75 schools are being investigated for allegedly levying fees in contravention of the Gujarat Self-Financed Schools (Regulation of Fees) Act, 2017; in Punjab, the high court has prohibited any fees or annual charge increases. School fees litigation is also pending in Haryana, Odisha and Jammu & Kashmir.

Prolonged and continuous litigation on the issue of the right of private school promoters and managements to determine fees payable, is rooted in ideological battles fought in the political arena in post-independence India. Despite the Constitution of India promulgated in 1950, bestowing a fundamental right to “practice any profession, or to carry on any occupation, trade or business,” upon all citizens, free India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru persuaded then dominant Congress party to develop the economy according to the tenets of a “socialistic pattern of society”. This resulted in all economic activities, occupations and businesses being subject to State control.

Justices of the Supreme and high courts fell in line, especially after the mid-1960s when Nehru’s super-socialist daughter Indira Gandhi was elected prime minister. She packed the Supreme Court with judges “committed” to socialist ideology. They dutifully endorsed nationalisation of banks, coal, electricity industries and multiplication of public sector enterprises (PSEs). Managed by business-illterate bureaucrats, PSEs started making huge losses ab initio. Simultaneously tight government controls were imposed on private industry, business, including private education. To the extent that the right to admit students of their choice and determine tuition fees was gradually taken away from private arts, science and commerce colleges, and especially from professional (engineering and medical) colleges.

Sengupta: indirect profit loophole

Ironically, the right of self-administration was totally taken away from professional education colleges two years after the then Congress government at the Centre led by the late prime minister Narasimha Rao with Dr. Manmohan Singh as finance minister, decreed the landmark liberalisation and deregulation of the Indian economy.

In Unni Krishnan vs. State of Kerala (1993), (state) governments were permitted to conduct a common entrance test (CET) for admission into all professional colleges, appropriate 50 percent of seats at nominal price, determine fees payable by non-government students (‘payment seats’) leaving a 10-20 percent ‘management quota’ under which college managements were permitted to charge discretionary fees to cross-subsidise tuition fees imposed by government. The five-judge bench held that education was a fundamental right of all citizens under Article 21 (which guarantees life and liberty). Therefore despite Article 19 guaranteeing the fundamental right to conduct a business/vocation, education cannot be a for-profit or commercial business. It must necessarily be a charitable and philanthropic vocation. The partial dissent of Justice Sahai advising administrative freedom for education institutions was over-ruled by the other four judges.

Unsurprisingly, the Unni Krishnan judgement choked the flow of private investment into education. Especially from bona fide edupreneurs invested with genuine human capital development idealism and philanthropic impulse. Consequently India with a 1.4 billion population hosts a mere 783 medical and 5,800 engineering colleges.

With profligate Central and state governments splurging on huge establishment and overheads expenditure and also doling out unwarranted subsidies to the middle class, they perennially run large fiscal deficits leaving little wherewithal for promoting capital-intensive professional education institutions. And with respectable private sector corporates and entrepreneurs put off from investing in education by red tape, over-regulation and widespread racketeering, new greenfield professional education colleges are mainly being promoted by politicians and shady edupreneurs with skills to manage the corrupt licensing and regulatory system. Therefore, teaching-learning standards are poor, prompting widespread ‘unemployability’ among engineering graduates in particular.

Providentially, after liberalization and deregulation of the economy in 1991 began showing good results — annual GDP growth rate more than doubled in the early years of the new millennium and EducationWorld (estb.1999) began exposing absurdities and corruption of the control-and-command education system — in 2002, in TMA Pai Foundation vs. State of Karnataka, an 11-judge bench of the Supreme Court revised its judgement in Unnikrishnan’s Case. It ruled that private professional colleges have a fundamental right to administer their admissions provided they are based on merit, and determine their own tuition fees provided they are ‘reasonable’.

Unfortunately, affirming the reality of “the lasting shadow of Nehruvian socialism” within the establishment (see book review p. 70) the very next year while professing to “interpret” the TMA Pai Case judgement, in Islamic Academy vs. State of Karnataka (2003) a five-judge bench of the apex court decreed appointment of fees regulation committees headed by retired high court judges in every state countrywide, to adjudicate whether fees charged by private professional colleges are reasonable. Deriving inspiration from this judgement, state governments across the country began establishing fees regulation committees for private schools as well. The outcome is the spate of litigation detailed above.

“Several judgements of the Supreme Court have confirmed that education provision has to be a charitable, not-for-profit activity. However in 2002 in the TMA Pai Foundation Case, the court ruled that private sector professional education colleges are entitled to levy fees that would earn them a reasonable profit/surplus for investment in capacity expansion and institution development. Interpretation of what is reasonable has prompted numerous state governments to enact legislation capping school fees. Yet the truth is that by outsourcing numerous school services such as bussing, campus maintenance, digital learning etc to for-profit firms managed by friends and relations, institutional promoters are indirectly earning profit from education provision. Thus they are able to indirectly do what is forbidden by law. There is no logic behind compulsorily making education a charitable activity when medical services and hospitalisation are not. Moreover over-regulation of education is preventing the inflow of clean, idealism-driven, philanthropic capital into education. This is not in the public interest,” says Arghya Sengupta, Director of the Delhi-based Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, an independent think-tank that conducts “legal research to make better laws and improve governance for the public good”. Promoted by Sengupta, an alumnus of the National Law School of India University and Oxford University (UK), the not-for-profit Vidhi Centre (estb.2013) has 297 employees on its musters.

“Several judgements of the Supreme Court have confirmed that education provision has to be a charitable, not-for-profit activity. However in 2002 in the TMA Pai Foundation Case, the court ruled that private sector professional education colleges are entitled to levy fees that would earn them a reasonable profit/surplus for investment in capacity expansion and institution development. Interpretation of what is reasonable has prompted numerous state governments to enact legislation capping school fees. Yet the truth is that by outsourcing numerous school services such as bussing, campus maintenance, digital learning etc to for-profit firms managed by friends and relations, institutional promoters are indirectly earning profit from education provision. Thus they are able to indirectly do what is forbidden by law. There is no logic behind compulsorily making education a charitable activity when medical services and hospitalisation are not. Moreover over-regulation of education is preventing the inflow of clean, idealism-driven, philanthropic capital into education. This is not in the public interest,” says Arghya Sengupta, Director of the Delhi-based Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, an independent think-tank that conducts “legal research to make better laws and improve governance for the public good”. Promoted by Sengupta, an alumnus of the National Law School of India University and Oxford University (UK), the not-for-profit Vidhi Centre (estb.2013) has 297 employees on its musters.

The downsides of the judiciary and government overlooking the fundamental rights conferred by Article 19 of the Constitution upon citizens to freely engage in the vocation of education provision have been repeatedly flagged by EducationWorld (estb.1999). With your editor as founding-editor of Business India (estb.1978) and Business World (1981), pioneer publications that planted the seeds of the 1991 economic liberalization and deregulation, having had the experience of chronicling the devastating impact of runaway neta-babu licence-permit-quota raj on industry and business, ab initio EducationWorld has been protesting migration of the licence-permit-quota regimen into the education sector.

Shomie Das RIP: over-regulation warning

For instance in July 2017 in a comprehensive cover story titled ‘Fees regulation fever endangering India’s private schools’ (https://www.educationworld.in/fees-regulation-fever-endangering-indias-private-schools/) we wrote: “A virulent fever with symptoms of irrational behaviour and myopia seems to be spreading through India’s 300 million-strong middle class. Across the country, middle class households who have opted to enroll their children in private unaided (i.e. financially independent) K-12 schools — and wouldn’t dream of enrolling their precious offspring in the country’s 1.5 million non-performing government schools — are clamouring for government ‘regulation’ of tuition fees levied by India’s estimated 320,000 recognised private schools. Evidently their collective judgement is impaired by this fever because they seem unmindful that government intervention and diminution of the autonomy of private schools — the sole bright spot of a dysfunctional education system — could be the first step towards levelling them down to the pathetic condition of government primary-secondaries defined by crumbling buildings, multi-grade classrooms, unusable toilets, mass teacher absenteeism and abysmal learning outcomes.”

That and other feature-length explanatory reports in EW seem to have had no impact on middle class parents who continue to invite incremental government intervention to depress private schools tuition fees. Nevertheless, they simultaneously expect school managements to provide globally benchmarked infrastructure and capital-intensive digital teaching-learning technologies and sports facilities. The late Shomie Das (1935-2024) who served a long career as headmaster of India’s most respected and routinely top-ranked private schools, offered middle class parents useful advice.

“Promoters invest huge sums of money to establish globally comparable schools. Therefore they are entitled to reasonable returns on their investment. If tuition fees are controlled by government which applies uniform ceilings on fees, education quality will suffer, with supplementary co-curricular and sports education the first casualty. Government interference with the tuition fees of private schools will gradually lead to incremental official interference in other administrative matters. There’s a real danger of India’s private schools suffering the fate of India’s universities ruined by government over-regulation,” warned Das, an alum of Presidency College, Kolkata and Cambridge University (UK) who began his academic career as a physics teacher in Gordonstoun School (UK), returned to India to serve long terms as principal of the top-ranked Doon School, Dehradun, Lawrence School, Sanawar and Mayo College, Ajmer.

Unfortunately for Indian education and the polity, such well-considered advice falls on deaf ears. Because of the legacy of almost half a century of socialism, resentment against private schools runs deep within the establishment and the middle class, averse to sending their children to free-of-charge government schools. During the Covid-19 years (2020-21) when in its questionable wisdom the Union government mandated the world’s most prolonged closure of schools (national average: 540 days), several state governments issued public notices advising parents not to pay tuition fees on the ground that school campuses had been shutdown. This notwithstanding the reality that institutional managements had incurred considerable expense installing digital infrastructure to switch to online learning, continuing to pay teacher salaries and maintain school campuses and facilities in anticipation of lifting of the lockdown.

Choksi (right): unintended outcomes

At that time (July 2020), in a cover story titled ‘Neta-babu Brotherhood Destroying Private Education’ we wrote: “State governments across the country have issued a spate of notifications and circulars ordering private school managements to waive or defer tuition fees for the March-June quarter. Coterminously, school managements are directed to continue to pay salaries and emoluments of their teachers and support staff. School promoters, principals and managements who fail to comply are being threatened with prosecution under several provisions of the Disaster Management Act, 2005. With parents of school-going children encouraged to breach their contract to pay their children’s school fees by confusing government notifications, and public sector banks reluctant to provide credit, a large and growing number of private schools — especially budget private schools — are laying off teachers and staff and contemplating closure”.

Again, a few months later (April 2021) in a cover feature titled ‘3-Prong Attack on Private Schools’, we reported that with the Central government denying them MSME status, state governments slashing tuition and other fees and parent communities unwilling to pay contracted fees, private schools — especially affordable Budget Private Schools (BPS) – were threatened with imminent closure (https://www.educationworld.in/3-prong-assault-on-private-schools/) .

However, all these warnings and admonitions have had little impact on most state governments which under pressure from middle class parents, have enacted tough fees regulation laws to control and contain private school fees.

Despite the ruling BJP/NDA government’s several initiatives to speed up industry and economic liberalisation and improve the ease of doing business, the BJP government of Gujarat enacted the Gujarat Self-Financed Schools (Regulation of Fees) Act, 2017. Under the Act, private schools, including pre-primary, primary, secondary, and higher secondary institutions prior to commencement of every academic year, are obliged to submit proposed fee structures to a Fee Regulatory Committee (FRC) for approval which is granted for three years with a 5 percent increase permitted annually. Schools levying fees without FRC approval or exceeding the sanctioned amount, are liable to pay stiff penalties of up to Rs.5 lakh for the first violation and higher for subsequent violation and/or withdrawal of recognition by the state government.

“The injustice of the Gujarat Self-Financed School Act is that whereas in other states, regulatory committees adjudicate annual fee increases, in Gujarat FRC determines the tuition fee chargeable by every private school for three years with an annual 5 percent increase. And although the base fee is supposed to be based on documentation presented by every school, the fees-setting process is arbitrary, based mainly on parents demands. The fees setting process of the FRC is non-transparent and varies widely for comparable schools. Consequently, there are a lot of unintended outcomes such as levying illegal admission fees, teacher layoffs and cutting corners in education delivery. As a result, genuine, idealistic education providers are reluctant to expand operations, creating opportunities for unscrupulous elements to enter education spaces. Indian education would greatly benefit if government would focus on developing government schools as our competitors. This would force private schools to reduce tuition fees,” says Manan Choksi, a qualified chartered accountant and executive director of the CBSE-affiliated Udgam School for Children, ranked Ahmedabad’s #1 co-ed day school in the EW India School Rankings 2024-25.

Bano: unsustainable financial burden

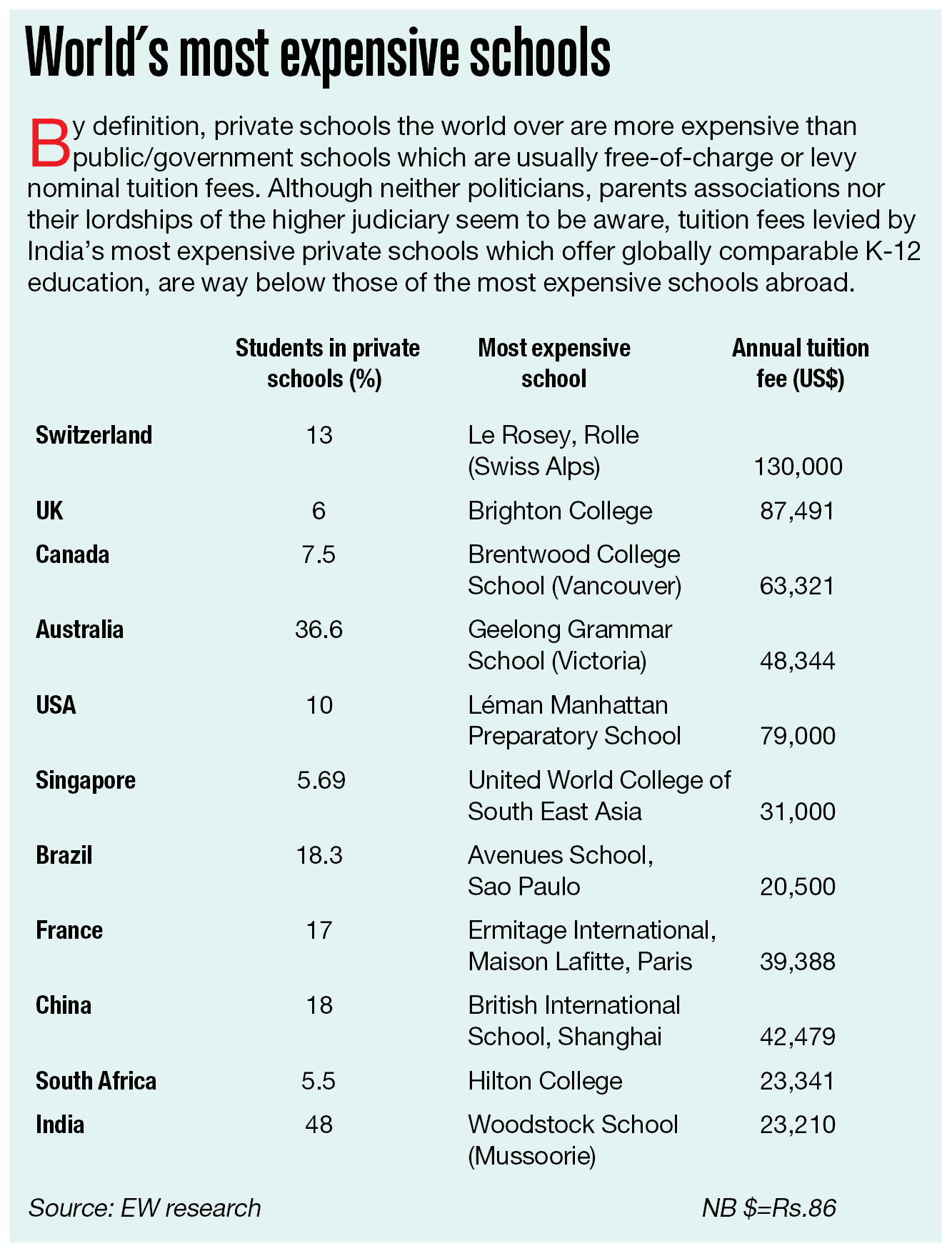

Despite the fact that private schools fees in India are arguably the lowest worldwide (see box p.39) parents’ call for government intervention to supervise and regulate fees of private schools is rooted in widespread belief that private school promoters and managements earn enormous profits. “Several surveys indicate that private school tuition fees in India have surged by 50-80 percent over the past three years, significantly outpacing the growth of middle-class incomes. For instance, in Delhi, the annual tuition fee at Delhi Public School, Vasant Kunj increased from Rs.90,000 in 2019–20 to Rs.1.7 lakh in 2024–25. In Tier 1 and 2 cities, annual fees of reputable private schools now range between Rs.1 lakh and Rs.4 lakh, while in Tier 3 and 4 cities, they range between Rs.50,000 and Rs.2 lakh. This trend underscores urgent need for regulation of private schools — not to undermine their autonomy, but to ensure that their managements adhere to their legal obligation of operating as non-profit, charitable organizations. Without effective oversight, the commodification of education continues unchecked, placing an unsustainable financial burden on families and threatening the principle of equitable access to quality education,” says Samina Bano, Founder and CEO of RightWalk Foundation, a Delhi-based NGO.

Nevertheless the situation is not all gloom and doom for edupreneurs who have invested savings, time and sustained effort to nurture education institutions inherited or promoted by them to develop the country’s huge, high-potential human resource. Some state governments aware of the pathetic condition of historically neglected public schools have negotiated satisfactory, mutually beneficial fees regulation agreements with private school promoters. A model agreement on this contentious issue has been negotiated between the incumbent BJP government of Uttar Pradesh and private schools in India’s most populous state by ARISE (Association for Reinventing School Education), “an autonomous body that brings together some of the country’s most progressive and intellectual minds including school promoters, edupreneurs & leaders who remain committed and focused on serving as a beacon for change within the diverse and dynamic landscape of India’s school education system.”

Sunbeam Group chairman Deepak Madhok: successful regulation model

“After detailed discussions with ARISE board members on the issue of smooth regulation of private schools fees, the state government enacted the Uttar Pradesh Fees Regulation Act, 2018 which could perhaps serve as a model for all states. Under the Act, private schools are permitted automatic annual fee increase calculated on the basis of rate of inflation according to the Consumer Price Index — plus 5 percent. This is applicable to in-school students. New students admitted have to pay contracted fees with annual increase as per the CPI + 5 percent formula. Any complaints are adjudicated by a District Fees Regulatory Committee. Since this Act was passed six years ago, it has worked very smoothly in Uttar Pradesh. It has also prompted many committed and reputed entrepreneurs to promote greenfield schools in UP. Moreover, increased supply has ensured school managements think twice about raising contract fees, and even fee increases within the permissible limit. UP’s fair and balanced private school fees regulation legislation is a success story and should be replicated countrywide,” says Deepak Madhok, an alumnus of Banaras Hindu and Allahabad universities, former civic administrator of the Uttar Pradesh Public Service Commission, and currently chairman of the Varanasi-based Sunbeam Group of Educational Institutions (SGEI). SGEI comprises nine owned and 17 associate schools, two women’s colleges, an autism centre and a free school offering vocational education. These institutions have an aggregate enrollment of 35,000 students mentored by 2,000 teachers.

Seventy-seven years after independent India began its tryst with destiny with high hopes and aspirations, the Central and especially state governments have failed to upgrade the country’s 1 million public schools — particularly in rural India which grudgingly hosts 60 percent of India’s 260 million households. Year on year, the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) published by the independent, highly respected Pratham Education Foundation has been chronicling that early teens in class VII-VIII can’t read class III texts or manage simple multiplication and division sums. Instead of focusing on remedying this grievous social injustice, the attention of education ministries at the Centre and in the states is focused on micro-management of the country’s 450,000 private schools which provide superior K-12 education. Consequently these schools — of whom the Top 4,000 are rated and ranked in the annual EducationWorld India School Rankings — are being forced to level down.

Seventy-seven years after independent India began its tryst with destiny with high hopes and aspirations, the Central and especially state governments have failed to upgrade the country’s 1 million public schools — particularly in rural India which grudgingly hosts 60 percent of India’s 260 million households. Year on year, the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) published by the independent, highly respected Pratham Education Foundation has been chronicling that early teens in class VII-VIII can’t read class III texts or manage simple multiplication and division sums. Instead of focusing on remedying this grievous social injustice, the attention of education ministries at the Centre and in the states is focused on micro-management of the country’s 450,000 private schools which provide superior K-12 education. Consequently these schools — of whom the Top 4,000 are rated and ranked in the annual EducationWorld India School Rankings — are being forced to level down.

Quite clearly, the time is nigh for the judiciary, government and middle class parents to revise their mindsets and cut private educationists and institutions a fair deal. Government needs to focus proactively on radically upgrading government schools and apply the logic of liberalisation and deregulation of industry and the economy to private schools.

Meanwhile the best available option for middle class parents with children in private schools is to form school-specific parents associations to collectively negotiate children’s school fees. Collective bargaining is a better option than inviting government fees regulation. India’s failed national development experience proves that inviting government intervention is to invite a sea of troubles.

Fees regulation legislation in major Indian states

Under the Constitution, education is a Concurrent List subject with the Centre and states entitled to enact legislation on this subject. Availing this provision almost all 28 states of the Indian Union have enacted legislation to regulate private school tuition fees.

Andhra Pradesh. Under the Andhra Pradesh Educational Institutions (Regulation of Admission and Prohibition of Capitation Fee) Act 1983, the state government is authorised to establish a District Fee Regulatory Committee (DFRC) to approve the fees of private unaided schools in all districts.

Arunachal Pradesh. The Arunachal Pradesh Education Act, 2010 empowers the state government to determine and regulate fees charged by private aided and unaided schools.

Assam. The Assam Non-Government Educational Institutions (Regulation of Fees) Act, 2018 mandates establishment of Fee Regulatory Committees to determine and approve fee structures of private schools for three years.

Bihar. The Bihar Private Schools (Fee Regulation) Act, 2019, permits private schools to increase fees by a maximum of 7 percent annually. Any increase beyond 7 percent requires prior approval from the state’s Fee Regulatory Committee (FRC).

Chhattisgarh. The Chhattisgarh Private School Fee Regulation Act, 2020 permits private schools to increase fees by a maximum of 8 percent annually. School-level Fee Committees and District Fee Regulatory Committees adjudicate increases.

Delhi. Fee increases are governed by the Delhi School Education Act and Rules, 1973. However, on April 30, 2025, the ruling BJP government of Delhi state approved a new Delhi School Education (Transparency in Fixation and Regulation of Fees) Bill, 2025, which proposes parents’ representation at every level of the decision-making process.

Goa. The Goa School Education Act, 1984 requires private unaided schools to submit fee structures to the Director of Education for approval before start of every academic year.

Gujarat. The Gujarat Self-Financed Schools (Regulation of Fees) Act, 2017 mandates annual fee ceiling for primary (Rs.15,000), secondary (Rs.25,000) and higher secondary (Rs.27,000) private schools. All schools proposing to levy higher fees must submit their proposals to a government Fee Regulatory Committee (FRC) for approval.

Haryana. The Haryana School Education (Amendment) Rules, 2022, permits annual fee increases based on the average percentage increase of teachers’ salaries and the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Himachal Pradesh. The Himachal Pradesh Private Educational Institutions (Regulation) Act, 1997 mandates all private schools to disclose fees payable when greenfield schools are established. The state government is invested with the authority to issue directions regarding the management of private education institutions, including fees chargeable.

Jammu & Kashmir. The Jammu and Kashmir School Education Act, 2002, mandates appointment of a Committee for Fixation and Regulation of Fee (FFRC) to determine and regulate the fees of private schools.

Jharkhand. The Jharkhand Education Tribunal (Amendment) Act, 2017 mandates the formation of fee fixation committees at the school and district levels. Proposed fee hikes above 10 percent require prior approval from the district committee.

Karnataka. The Karnataka Education Act, 1983, empowers the state government to determine fees chargeable by private schools. In 2023, the Karnataka High Court struck down several sections of the Act as unconstitutional.

Kerala. The Kerala Education Act, 1958 and Kerala Education Rules, 1959 empower the government to regulate fees charged by private schools to “prevent exploitation”.

Madhya Pradesh. According to the Madhya Pradesh Private Schools (Fee and Related Matters Regulation) Act, 2020, which came into effect in 2025, private unaided schools are permitted to automatically raise fees by up to 10 percent annually. Beyond 10 percent, they must obtain approval of a district-level fee regulation committee.

Maharashtra. The Maharashtra Educational Institutions (Regulation of Fee) Act, 2011 requires every unaided private school to constitute an executive committee comprising PTA members to approve the fee structure proposed by the school management. In instances of differences between the committee and management, a Divisional Fees Regulatory Committee (DFRC) is empowered to adjudicate.

Manipur. The Manipur Private School (Registration and Regulation) Act, 2017 empowers government to “regulate the rates of fees, the levy, and collection of fees in private schools”.

Meghalaya. The Meghalaya School Education Act, 1981 mandates the managing committee of every recognised private school to file with the appropriate authority a full statement of fees to be levied before the new academic year.

Nagaland. The Nagaland Board of School Education Act, 1973 authorises the board to prescribe and regulate fees in all state board-affiliated schools.

Odisha. A Government Resolution issued by the state’s School and Mass Education Department in 1996 provides for fee regulation of private schools.

Punjab. The Punjab Regulation of Fee of Unaided Educational Institutions Act, 2016 permits private unaided schools to increase fees by a maximum of 8 percent annually. Any increase beyond this limit requires prior approval of the district regulatory body.

Rajasthan. Under the Rajasthan Schools (Regulation of Fee) Act, 2016, every private school in the state is obliged to constitute a School Level Fee Committee (SLFC) comprising representatives of the management, principal, teachers and PTA. If the SLFC fails to agree on the fee, the matter is adjudicated by a Divisional Fee Regulatory Committee.

Tamil Nadu. Under the The Tamil Nadu Schools (Regulation of Collection of Fee) Act, 2009, a district committee determines the maximum fee that can be charged by private unaided schools in every district for a period of three years.

Telangana. The Telangana Private Schools and Junior Colleges Fee Regulatory and Monitoring Commission Draft Bill, 2025 proposes a biannual hike linked to the Consumer Price Index.

Uttar Pradesh. The UP Self-financed Independent Schools (Regulation of Fees) Act, 2018, permits a private unaided school “by itself” to increase fees annually for in-school students, but the “fee increase shall not exceed latest available yearly percentage increase in consumer price index + 5 percent of the fee realised from the student”. New students admitted have to pay contracted fees with annual increase as per the CPI + 5 percent formula.

Uttarakhand. The Uttarakhand School Education Act, 2006, prohibits private schools from accepting fees beyond the “rates” specified by the state government.

West Bengal. The TMC government hasn’t yet tabled the West Bengal Private Schools Regulatory Bill, 2022, in the state legislature. The Bill proposes setting up a Commission to determine the fees charged by private schools and hear complaints.

Also Read: Private school fees status across India

Add comment