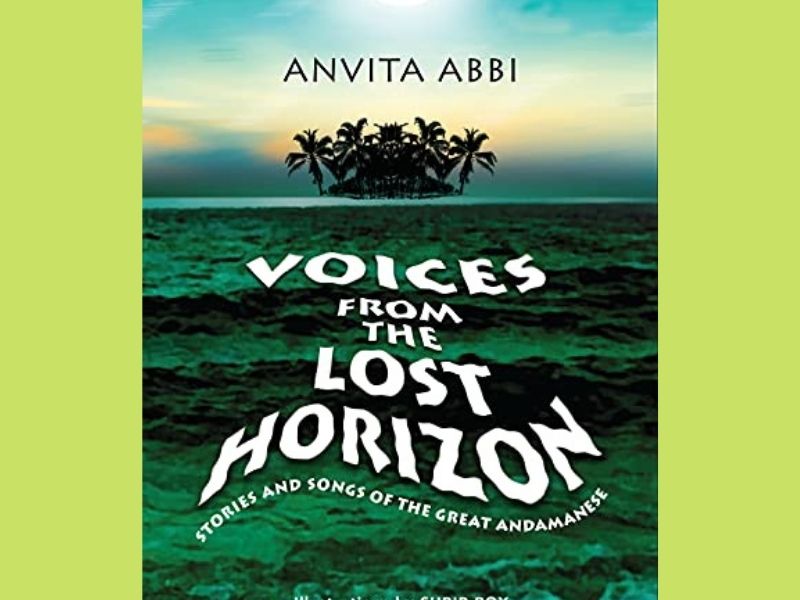

Voices from the lost horizon: stories and songs of the great Andamanese

By Anvita Abbi

Niyogi books

Rs.995 Pages 176

This book records remembered stories and songs retrieved from linguistic and cultural amnesia. The history of migrant tribes from Africa is reconstructed, writes Jayati Gupta

Written by experienced researcher and academic Anvita Abbi, this book is essentially a valiant appeal to preserve the fragile status of the languages, beliefs and practices of tribes that are remnants of the first migration from Africa to South Asia almost 70,000 years ago. These tribes settled and remained isolated in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands until the mid-19th century, when the British India government designated the islands a penal colony.

A valuable work of linguistic and ethnology research, Stories & Songs imaginatively illustrated by Subir Roy, features indigenous Great Andamanese songs written in Roman script with English translation. They provide readers glimpses of an extraordinary socio-cultural environment, and a learning experience about an integral but neglected region of post-independence India.

This book records remembered stories and snatches of songs retrieved from linguistic and cultural amnesia. In the process, languages/voices that have been forgotten regain vitality, and the history of the islands where migrant tribes from Africa began life as hunter-gatherers is reconstructed. The myth of Phertajido, the first man of the Andaman Islands who lived alone and searched for food, and made bows and arrows is recounted by Nao Jr, one of the Great Andamanese adults in the eight households of Strait Island that make up the community.

Initially, the narration started in Andamanese Hindi, because Great Andamanese had slipped into oblivion. Yet persistent jogging of tribal memory completes the tale of the first man who discovered drinking water from a spring, foraged potatoes from soil, discovered dhoop that generated fire and kaut, fine soil out of which he not only made pots but carved a human look-alike sculpture. How the figurine comes alive and laughs, the joy of discovering a companion, the peopling of a clan, form part of the Phertajido myth.

Phertajido’s wife makes a rope with creepers found in the jungle. Phertajido ties a stone to it and throws it up in the sky where it gets entangled creating a pathway to outer space. The philosophical climax of the story is about finding another world and deciding to retire into the clouds, climbing up the rope from earth and cutting it off after their time on earth was done.

Language is only nominally a medium of communication. There other media that records cultures mirror their social ethos, distinctive environment and worldview. The ten stories and 46 songs in the surviving native language, a mixture of four northern varieties of Great Andamanese (Jeru, Khora, Bo, Sare) are part of an oral culture that encapsulates history, philosophy, beliefs and values of these forgotten people. Such ardous fieldwork initiatied in 2005 and meticulous documentation subsequently, has preserved the diversity and richness of an ethnic heritage from completely slipping away. Nao Jr and Boa Sr who were infected by Abbi’s enthusiasm to revive a critically endangered language, died in 2009 and 2010 respectively, carrying away with them precious indigenous knowledge and the last vestiges of racial memory.

Luckily for poster, advanced technology has enabled these lost voices to come alive via interactive QR codes provided at the end of each chapter through which some audio-visual recordings can be accessed. Besides the narrative of ethnogenesis, the other narratives explore the symbiotic relationship between language and environment.

In a tale Maya Jiro Mithe, a boy from the Jero tribe who lived by the seashore is swallowed by a Bol fish and rescued by friends led by Kaulo. The stomach of the Bol fish is cut up to release the trapped Mithe crouching inside. There was general excitement about cutting up the massive fish to be roasted on the machaan, but inadvertently a nerve of the fish that was tossed into the fire burst with a loud bang and all the children and boys were turned into birds. This story of evolution explains why birds are revered as the ancestors of the Andamanese.

Inevitably in primitive civilisations, cultural values are handed down from one generation to the next by way of songs and oral narratives. The Tale of Maya Lephai narrates a story of love, betrayal and honour killing in the hills of Bontaing, the indigenous name of the north side of the Jarawa Reserve near Bluff Island in the Middle Andamans. Social practices like cannibalism and funeral rites for different types of death — natural death, hunting deaths, death by choking on a bone, deaths of children — form the theme of The Tale of Juro, the Headhunter.

Several stories are lessons in environment sustainability. They advocate conservation of indigenous knowledge and the advantages of shared living in clans. This reminds one of the 2004 tsunami that transformed the geo-topographical structure of the islands. On the occasion, it was older members of the tribes who identified trees that saved many lives, advised shelter on higher ground to beat high waves and used their cognitive skills and racial memory to survive the force of the tsunami.

Even Present-day Great Andamanese (PGA) which became an endangered language in the early years of the 21st century has become extinct. What remains are stories and songs rescued from oblivion because of the trust built between Abbi and natives, urging them to remember and share. The outcome is this amazing collection that counters the British myth that the Andamanese were savages.

The loss of their native culture and languages began with European colonialism, persisted with official apathy in independent India and society’s indifference towards conservation and environmental degradation.