Against the backdrop of growing wealth inequality and hunger, a rising wave of philanthropy funding is gathering momentum around the world and in India. According to the Global Philanthropy Report 2021, the education sector is specially favoured by philanthropic foundations and high networth individuals, writes Dilip Thakore

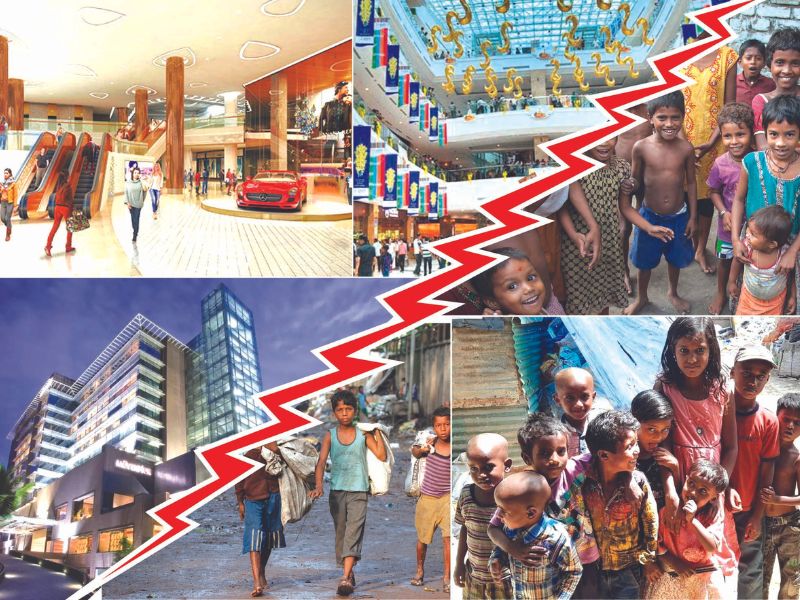

Contrasting images of 21st century India: favourable philanthropy ground conditions

TWO MOMENTOUS RECENTLY released reports on the eve of the 23rd anniversary of EducationWorld — The Human Development Magazine (regst.1999), have the potential to greatly influence the future of India’s children who despite loud official protestations to the contrary, are floundering in shallows and misery.

On October 11, Oxfam International released the fourth edition of its Commitment to Reducing Inequality Index (CRII) 2022. The index reviews the “spending, tax and labour policies and actions” of 161 countries worldwide, including India, during the period 2020-22. “Covid-19 has increased inequality worldwide, as the poorest people were hit hardest by both the disease and its profound economic impacts. Yet CRII 2022 shows clearly that most of the world’s governments failed to mitigate this dangerous rise in inequality. Despite the biggest global health emergency in a century, half of low and lower-middle-income countries saw the share of health spending fall during the pandemic, half the countries tracked by the CRI Index cut the share of social protection spending, 70 percent cut the share of education spending, while two-thirds of countries failed to increase their minimum wage in line with gross domestic product (GDP). Ninety-five percent of countries failed to increase taxation of the richest people and corporations. At the same time, a small group of governments from across the world bucked this trend, taking clear actions to combat inequality, putting the rest of the world to shame.” As a special India report included in this survey elaborates, the government of India — a perennial laggard in social welfare spending, especially on education and healthcare — isn’t in the latter category.

Although Oxfam International is well-known for its left of centre ideological moorings, its experience of conducting wealth inequalities, poverty measurement and hunger surveys for over eight decades commands respect, even if the anti-diluvian solutions anchored in obsolete communist/ socialist ideology, are suspect. Founded by Oxford University academics way back in 1942, Oxfam has established a global reputation for fundraising to provide financial and rehabilitation aid to people and communities devastated by calamities such as floods, earthquakes, famine, war etc. Currently, its international secretariat is based in Nairobi (Kenya) with offices in Addis Ababa, Washington D.C, New York, Geneva, and Brussels. Moreover, it has eponymous affiliates in 21 countries including India (estb.2008), an annual budget of $ 1 billion and 196 employees worldwide on its pay roll. In short, its survey reports and data — even if not its solutions — need to be accorded great respect.

Perhaps coincidentally but simultaneously, two other respectable NGOs — the Dublin (Ireland)-based Concern Worldwide (estb.1968) and the Bonn (Germany)-based Welthungerhilf (1962) — published the Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2022, in which India is included among 35 countries suffering ‘serious’ mass hunger. “The hunger levels in both South Asia (where hunger is greatest) and sub- Saharan Africa (where hunger is second greatest) are considered serious. South Asia has the highest child stunting rate and by far, the highest child wasting rate of any world region. Africa South of the Sahara has the highest prevalence of undernourishment and rate of child mortality of any world region. East Africa, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia are experiencing one of the most severe droughts of the past 40 years, threatening the lives of millions. According to forecasts, the climate crisis will be a key factor preventing the world from achieving the second UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 2), ‘Zero Hunger’ by 2030,” warn the authors of GHI 2022.

Although ex facie these two deeply researched and authoritative reports — dismissed by government spokespersons (economics pundit Swaminathan Aiyar, consulting editor of the Economic Times rubbishes GHI 2022 as “statistical garbage”) as extensive tomes written with the sole purpose of maligning India — represent cause and effect, they contain the seeds of a solution. Oxfam’s CRII report provides ample evidence that there’s a large pool of rich citizens in poor India and their number is fast rising.

According to CRII 2022, whereas there were nine US dollar billionaires in India in the millennium year (2000), their number increased to 101 in 2017, and currently there are US dollar 119 billionaires countrywide. Moreover, the authors of the index estimate that the number of rupee millionaires in India rose by 70 per day during the period 2018-22, despite Covid-19 severely disrupting business and the economy. Quite clearly, ground conditions for practice of serious philanthropy to end child hunger and nurture the country’s next generation are promising.

National focus on nurturing generation next is important because the brunt of hunger and malnutrition in 21st century India, is borne by children. According to GHI 2022, 16.3 percent of India’s population is under-nourished with children worst hit. The authors of GHI are forthright and unequivocal: “India ranks 107th out of the 121 countries with sufficient data to calculate 2022 GHI scores. With a score of 29.1, India has a level of hunger that is serious,” they write.

Moreover it’s pertinent to note that the ‘trend values’ of GHI 2022, i.e, metrics to measure hunger are heavily focused on children. The report estimates the proportion of under-nourished population (India: 16.3 percent); child stunting (share of children under age five who have low height for their age, reflecting chronic under-nutrition): 35.5 percent; child wasting (share of children who have low weight for their height): 19.3 percent and child mortality (share of children who die before their fifth birthday, partly reflecting the fatal mix of inadequate nutrition and unhealthy environments): 3.3 percent.

You cant read further without a subscription. If already a subscriber please Login or to subscribe click here