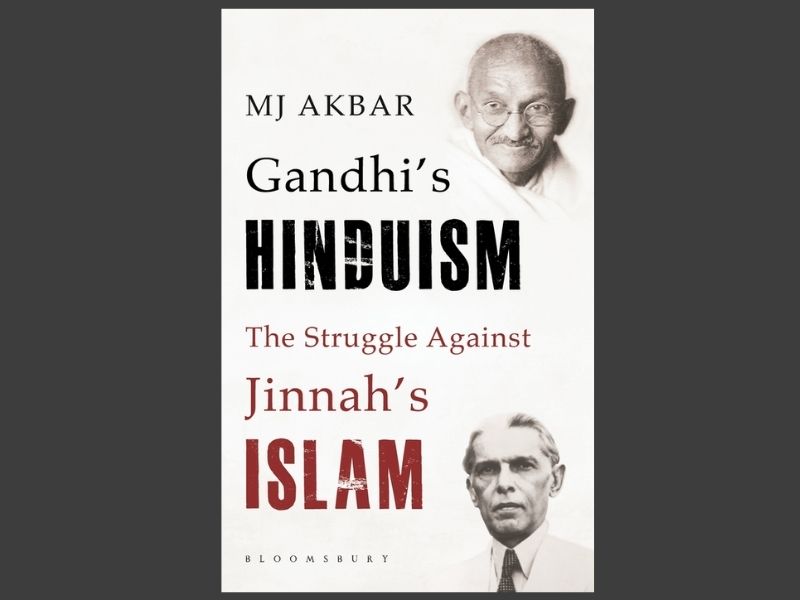

Gandhi’s Hinduism — The struggle against Jinnah’s Islam; M.J. Akbar; Bloomsbury; Rs.699; 414 pp

This compelling narrative tracking events to the final run-up to independence and partition of the subcontinent has suffered a media blackout, despite being authored by media supernova M.J. Akbar, (Sunday, The Telegraph, Kolkata, Asian Age and author of several contemporary histories including Nehru: The Making of India (1998) and Tinderbox: Past & Future of Pakistan (2011). That’s probably because Akbar is in the national doghouse following his trial by frothing TRP-obsessed television news anchors on unsubstantiated sexual harassment charges, which has also cut short his political career as a junior minister of the incumbent BJP-led NDA government at the Centre.

The title of Akbar’s latest oeuvre which suggests that the protagonists of this book were deeply religious personalities, is misleading. Though Gandhi was a devout Hindu, he was more a religious reformer than an orthodox practitioner of this ancient creed. His whole life was a struggle to excise the inherent inequities of the Hindu caste system, particularly the open, continuous and uninterrupted atrocities visited upon the lowest castes for millennia. Jinnah, on the other hand as Akbar recounts with numerous lifestyle examples and data was — like his Hindu alter ego Jawaharlal Nehru — a westernised sophisticate with ill-concealed disdain for religion and ritual, and at best a political Muslim. But he exerted powerful influence on his community.

However, though Akbar believes that it was Jinnah’s antagonism towards Gandhi that infuriated the former and ultimately compelled him to press the demand for a separate nation for the subcontinent’s Muslims, there is sufficient evidence in this and other histories of India’s freedom struggle to suggest that Jinnah’s worst fear was to be obliged to serve under Nehru. The latter was adopted by Gandhi as his “spiritual son” and favourite right from the time the 29-year-old Jawaharlal, spoilt offspring of wealthy lawyer Motilal Nehru, succeeded his father as Congress president in 1929.

To its merit, this fluent narrative also provides satisfying context and explanation for the sustained loyalty of the British to Jinnah. The plain truth obfuscated by most Indian historians, but highlighted by Akbar, is that in the early years of World War II, the British were in a blue funk following German dictator Adolf Hitler’s march through Europe and imminent invasion of Britain, and the quick conquest of the Philippines, Indonesia and Singapore by Japan, Hitler’s ally. Therefore, the loyalty and support of the Indian Army, 40 percent Muslim — at the height of the “bloodiest war in history,” writes Akbar, 2.5 million Indians were fighting for Britain deployed in Europe and Asia — was vitally important for imperial Britain. It was fighting lone wars on two fronts, because until end 1941, America was not a combatant nation.

As Akbar narrates in considerable detail, at this critical moment in the history of World War II, in March 1940, Jinnah offered the British viceroy Lord Linlithgow full Muslim League and community support for the war effort. “Linlithgow in return gave an undertaking that there would be no settlement on the future structure of India without the concurrence of Muslims,” documents Akbar.

On August 8, 1940, in an officially titled The August Offer “issued with the authority of His Majesty’s Government,” Linlithgow publicly confirmed the undertaking he had given Jinnah six months earlier.

But even if the British never wavered from this commitment, Jinnah did. Following prolonged discussions detailed in extenso by Akbar, on June 7, 1946 an ailing Jinnah hesitantly agreed to drop his demand for a separate nation and agreed to form an interim Congress-Muslim League federal government at the Centre, with elected autonomous governments in the provinces. For himself he wanted the defence portfolio in the interim government. However, the very next day Jinnah warned that “any departure from this formula, directly or indirectly, will lead to very serious consequences, and will not secure the co-operation of the Muslim League”. This formula was accepted by the Congress Working Committee which in effect overruled Gandhi.

Unfortunately a few months earlier in April, despite not one of the 15 provincial units of the Congress party voting for him and expressing overwhelming support for Sardar Patel, Nehru was appointed president of the Congress party to succeed Azad at the insistence of Gandhi, who knew full well that the party president would automatically be the first prime minster of independent India.

In a detailed chapter titled ‘Nehru’s Historic Blunder’, Akbar narrates how Nehru torpedoed the June 7 concordat. Addressing a press conference on July 10, Nehru asserted that Congress had only agreed to the establishment of a Constituent Assembly. “What we do there, we are entirely free to determine. We have committed ourselves on no single matter to anybody,” he said. This provided Jinnah “confirmation of Congress deceit… and the loophole through which he could backtrack on India’s unity,” writes Akbar. Exactly a year later, Pakistan became a fully independent and sovereign state.

Although this book ends with the assassination of Gandhi on January 30, 1948 and Jinnah’s death nine months later (September 11, 1948), it provides telling evidence of the damage that Nehru — who subsequently as prime minister led free, high-potential India down the disastrous socialist road to national bankruptcy and nurtured the unyielding tree of the Nehru-Indira dynasty which has reduced the Congress party to a shadow of its greatness did.

The title of this deeply researched and fluently written history suggests that it is all about Gandhi and Jinnah, the dominant personalities of the last days of the British Raj. Parallelly, it’s also the story of Jawaharlal Nehru’s ascendency to the most powerful office of post-independence India with tragic consequences for two generations — and counting — of free Indians floundering in shallows and misery.

Also read: Compelling narrative: China’s transformation