Shivani Chaturvedi (Chennai)

Dr. S. Somasundaram

In a not unexpected setback to the state government, on April 4, President Draupadi Murmu ( on advice of the Union government) declined to give her assent to the Tamil Nadu Admission to Undergraduate Medical Degree Courses Bill, 2022. The Bill sought to exempt higher secondary school graduates from the state from writing the National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (NEET) for admission into medical colleges countrywide. In 2017, the Central government enacted legislation making NEET the common nationwide exam for admission into all of the country’s 700 medical colleges.

Tamil Nadu’s DMK government had ab initio rejected NEET on grounds that the common entrance exam violates the federal spirit of the Constitution and disadvantages rural students who can seldom afford test prep/coaching classes necessary for the nationally standardised NEET.

Reacting to President Murmu’s rejection of the state government’s Bill, Tamil Nadu Chief Minister MK Stalin described it as a “dark chapter in federalism”. And inside the state, rejection of the Bill which decreed admission into Tamil Nadu’s medical colleges for toppers of the state’s higher secondary exam, has triggered a new wave of debate about the demerits of centralised exams, social equity, and states’ autonomy in education.

Within Tamil Nadu, there is an all-party consensus that NEET will hinder the state’s progress towards the ideals of social justice and educational parity. Since the exam’s introduction in 2017, the state’s dominant Dravidian pride political parties — DMK and AIDMK — have been on the same page contending that the English and Hindi dominated NEET format disadvantages students from rural and economically weaker households — especially students of Tamil-medium government schools. They argue that until 1976, when it was shifted to the concurrent list of the Constitution, education was a state government subject. Therefore, they want the status quo ante on the issue of medical college admissions.

In support of the contention that rural and Tamil-medium students are disadvantaged by NEET, the DMK government cites data drawn from the findings of a specially appointed committee chaired by Justice A.K. Rajan, a retired judge of the Madras high court, which found that after the introduction of NEET, the share of rural students in Tamil Nadu’s government medical colleges plunged from 61.45 percent to 50.81 percent, and of students from Tamil-medium schools from 14.88 percent to a mere 1.99 percent. On the other hand, the share of students from English-medium schools surged to 98.01 percent. The suicide in 2017 of S. Anitha, a Dalit student who had passed the school-leaving class XII exam of the Tamil Nadu state board with flying colours but failed to make the cut in NEET, is etched in public memory of the iniquity inherent in the centralised NEET.

Comments education consultant and student counsellor Manickavel Arumugam, a highly qualified alumnus of Annamalai University, Guindy Engineering College, and the National University of Singapore: “NEET has its advantages and disadvantages. It is a common national entrance test that eliminates school-leavers writing multiple entrance exams. Also, before NEET, there wasn’t normalisation of class XII marks in Tamil Nadu. That put students from outside the state at a disadvantage. Against this the centralised nature of NEET can cause delays, and a glitch in one part of the system affects all.”

Moreover, lax assessment was a fatal flaw of the earlier system where medical college admissions were based on class XII exam board scores. “The board exams-based model was flawed. Thousands of students scored full marks making it impossible to differentiate the truly meritorious from rote learners. Plus, students from schools affiliated with boards other than the Tamil Nadu state board couldn’t compete. This resulted in widespread corruption, with medical college seats being sold at exorbitant prices. NEET has helped reduce such malpractices and brought in fair nationwide competition,” he adds.

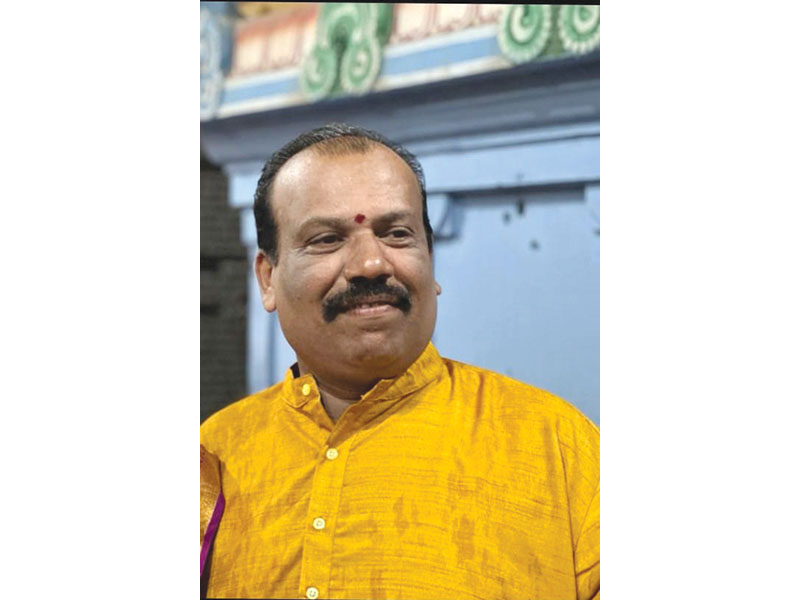

Dr. S. Somasundaram, a Chennai-based educationist, argues for reform over resistance. “Rather than seeking exemption, the state should equip students to fare well in NEET. The state government should provide TN and rural students scholarships, free-of-charge study material, and upgrade government schools. A uniform exam like NEET brings transparency. Tamil Nadu needs to expand its medical infrastructure, promote more medical colleges which would translate into more seats, which will democratise access to medical education. Tamil Nadu’s 38 government medical colleges and 39 private institutions, including deemed universities, are too few in number for a state with a population of 72 million,” says Somasundaram.

Nevertheless within the ruling DMK and opposition parties there’s near consensus that the NEET admissions model is fundamentally incompatible with Tamil Nadu’s commitment to placing the interests of the state’s backward classes and historically discriminated scheduled castes and tribes above all other considerations. On April 9, the DMK convened an all-party meeting in Chennai, where leaders unanimously resolved to seek judicial intervention and continue pressing for exemption of TN students from having to write NEET.