Somewhat surprisingly across India, the lead in promoting vocational education and training (VET) in a big way has been taken by the eastern seaboard state of Odisha and its BJD government led by the Doon School & St. Stephen’s College educated Naveen Patnaik, serving an unprecedented third term in office as chief minister – Autar Nehru

One of the major blindspots of post-independence India’s dysfunctional education system is vocational education and training (VET). Curiously, the omniscient czars of the Soviet-inspired Planning Commission, established soon after independence from almost 200 years of rapacious British rule over the Indian subcontinent, accorded low priority to education and human capital development, and even lower priority to VET. Despite central planners in the Soviet Union according to high importance to education — especially primary education — their Indian disciples were unconvinced. Annual investment (Centre plus states) in human capital development in post-independence India has averaged 3.5 percent of GDP and never exceeded 4 percent despite the high-powered Kothari Commission (1966) strongly recommending 6 percent of GDP.

One of the major blindspots of post-independence India’s dysfunctional education system is vocational education and training (VET). Curiously, the omniscient czars of the Soviet-inspired Planning Commission, established soon after independence from almost 200 years of rapacious British rule over the Indian subcontinent, accorded low priority to education and human capital development, and even lower priority to VET. Despite central planners in the Soviet Union according to high importance to education — especially primary education — their Indian disciples were unconvinced. Annual investment (Centre plus states) in human capital development in post-independence India has averaged 3.5 percent of GDP and never exceeded 4 percent despite the high-powered Kothari Commission (1966) strongly recommending 6 percent of GDP.

The socio-economic impact of continuous under-investment in human capital development for seven decades is that the country’s population has tripled because central planners were unaware that “education is the best contraceptive”. Moreover, with the majority rural population at best functionally literate, agriculture yields are pathetically low despite over-use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides which has resulted in despoliation of soil across vast stretches of land. In Punjab — the breadbasket state of India — per-hectare wheat and rice yields are one-fifth of China’s and one-tenth of France and the US. In Indian industry, the outcome of poor quality education in general and VET, in particular, is low productivity of shop floor and technical workers — a mere tenth of industrial workers in OECD countries.

The foolishly neglected issue of VET entered the radar of government and policy makers after the dirigiste red-tape bound Indian economy was partially liberalised and deregulated in 1991. This was mainly due to the efforts of iWatch (estb.1992), an NGO registered by IIT-Bombay alumnus Krishan Khanna who quit a promising career in India Inc (Crompton Greaves) to promote the cause of VET. Subsequently, in the new millennium a small band of prescient educationists (and EducationWorld) began highlighting this gaping lacuna in the country’s education system and connected it with rock-bottom productivity of Indian agriculture, industry and labour.

In 2009, the Congress-led UPA-II government belatedly established the National Skill Development Corporation (NSDC) with the mandate to rapidly skill the country’s population. NSDC’s mission was to build a sustainable ecosystem and promote skills development through provision of long-term loans to private sector VET firms, set up sector skill councils with employer engagement to prescribe standards and benchmarks, accredit training institutions to certify trainees, and encourage industry to employ trained personnel. However, a decade later, NSDC has had limited success with allegations that it recklessly awarded loans and contracts to private VET partners providing sub-standard training and courses. Moreover, the BJP/NDA government’s flagship Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY), launched in 2015 with the ambitious target of training 10 million youth between 2016-2020, has also proved a damp squib. It has trained 4.1 million over the past three years of whom just 615,000 — a mere 15 percent — have secured employment.

Against this depressing backdrop of VET in disarray, the 484-page National Education Policy (NEP) Draft 2019 of the nine-member Kasturirangan Committee — whose major recommendations are likely to be accepted and included in the final NEP by the Union HRD ministry — again stresses the importance of VET. It strongly recommends integration of vocational training into mainstream education — schools, colleges, and universities — and sets the government a target of “providing vocational education to at least 50 percent of all learners by 2025”.

With education provision and promotion on the concurrent list of the Constitution and the BJP/NDA government at the Centre according to low priority to education, the onus of promoting VET has devolved upon state governments. And surprisingly among the states, the lead in promoting VET in a big way has been taken by the eastern seaboard state of Odisha (pop. 45 million) and its BJD (Biju Janata Dal) government led by the Doon School & St. Stephen’s College educated Naveen Patnaik serving an unprecedented third term in office as chief minister.

In 2016, the BJD state government established the Odisha Skill Development Authority (OSDA) with a broad mandate to reinvigorate vocational education and training provided by Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs) and polytechnics; focus on WorldSkills and other competitions to make vocational education aspirational among youth; create and support a community of skills entrepreneurs known as Nano Unicorns, and provide industry/placement-linked skill development short-term courses under Central/state government schemes.

Since then, the OSDA (annual budget: Rs.592.30 crore in 2018-19) has skilled 990,000 youth across the state, launched a massive drive to upgrade and contemporise the state’s 49 ITIs, modernised 320 vocational education centres providing training in 167 trades to school drop-outs, and increased enrolment of girl students in technical courses by 18 percent. Moreover, OSDA has the distinction of nurturing the country’s first-ever gold medalist in the annual WorldSkills 2019 competition staged in Kazan (Russia) last August. Bhubaneswar-based electronics engineer Aswatha Narayana Sanagavarapu (25) bested participants from ten countries including South Korea, China, Germany, Russia, Iran and Brazil to be adjudged India’s first gold medallist in the individual water technologies management skills category.

Though most state governments have launched VET drives with little to show for them, Odisha has emerged as the VET leader state of the Indian Union largely because of the drive, energy and commitment of son of the soil, Patnagarh-born Subroto Bagchi, appointed chairman of OSDA with cabinet rank in 2016. A political science graduate of Utkal University, Bagchi began his career as a clerk in the industries ministry of the Odisha state government in 1976. A year later, he quit the civil service and was inducted as a management trainee in the DCM Group — a big name in Indian industry at that time. This was followed by stints in several IT companies, the longest being at Wipro Ltd (1988-1998) where he rose to the position of chief executive of Wipro’s Global R&D.

Though most state governments have launched VET drives with little to show for them, Odisha has emerged as the VET leader state of the Indian Union largely because of the drive, energy and commitment of son of the soil, Patnagarh-born Subroto Bagchi, appointed chairman of OSDA with cabinet rank in 2016. A political science graduate of Utkal University, Bagchi began his career as a clerk in the industries ministry of the Odisha state government in 1976. A year later, he quit the civil service and was inducted as a management trainee in the DCM Group — a big name in Indian industry at that time. This was followed by stints in several IT companies, the longest being at Wipro Ltd (1988-1998) where he rose to the position of chief executive of Wipro’s Global R&D.

In 1999, Bagchi co-founded Mindtree Ltd in Bangalore, and over the next two decades developed it into a $1 billion (Rs.7,200 crore) global IT services company with a head count of 20,000 employees. In May 2016, responding to an invitation of chief minister Patnaik to return to Odisha to lead the state’s charge into VET, Bagchi accepted the challenge and took office as executive chairman of OSDA at a token annual salary of Re.1 per year.

Since then, but for three months (March-May 2019) when he took a sabbatical to return to Mindtree to fight a hostile takeover bid by Larsen & Toubro Ltd, Bagchi has been at the helm in OSDA, driven by the mission to transform Odisha into a national skills education hub. “In 2016, when chief minister Naveen Patnaik invited me to lead OSDA, I realised that this was a great opportunity to give back to the state where I was born. The main objective of OSDA is to transform Odisha into India’s #1 VET state. Therefore, over the past three years, we have modernised the state’s 49 ITIs, set up advanced skills centres, established industry linkages, and encouraged enrolment of girl children in VET programmes. I am pleased to say that we are implementing all these initiatives in mission mode and Odisha is well on its way to transforming into India’s model skills education state,” says Bagchi.

A well-travelled corporate professional and IT entrepreneur, Bagchi has chosen to adopt and adapt the Singapore VET promotion model. In 2017, OSDA signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with ITE Education Services (ITEES), a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Institute of Technical Education (ITE), Singapore (estb.1992), a government-promoted public VET institution that provides skills training to secondary school-leavers, and continuing education to in-service industry professionals.

According to Bagchi, ITE has played a major role in transforming this island republic into Asia’s most economically advanced country with a per capita income of $64,582 (Rs.46 lakh) per year. “When Singapore became independent in 1965, the very existence of its people was at stake. It had no natural resources, not even potable water. They turned to the only resource they had, human capital, educating and training them in skills and trades. Their ITE system, equivalent of our ITIs, is at the heart of this success,” says Bagchi.

In 2018, 100 technical and vocational education & training (TVET) leaders including ITI principals and vice principals of 49 government ITIs attended a two-week training programme in ITE, Singapore to learn about latest VET pedagogies and practices. Bagchi believes they’ve returned with new insights and are actively collaborating with OSDA to introduce best VET pedagogies in the ITIs. Moreover, seven government ITIs of Odisha — ITI-Berhampur (automobiles), ITI-Balasore (electricals), ITI-Cuttack and ITI-Rourkela (production & manufacturing), ITI-Hirakud (process plant maintenance), ITI-Bhawanipatna (fabrication) and ITI-Bhubneshwar (IT) — are being modernised into centres of excellence.

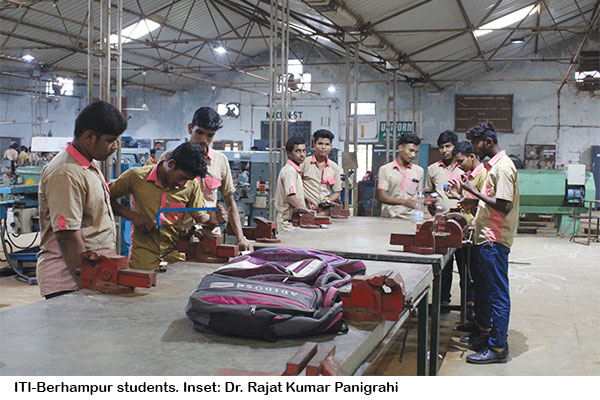

Included in this select club is ITI, Berhampur (ITI-B), promoted by the state government in 1957, one of the country’s oldest ITIs with an excellent academic and placement record. Set within a 9.72-acre campus, ITI-B has been transformed into a modern VET institution with Smart classrooms, industry-size training workshops, library, auditorium, playing fields, separate hostels for men and women students, and a sui generis craft museum displaying mechanical, automobile and other models created by students from metal scrap and industrial waste. The institute has been listed in the Asia Book of Records (2018) for its 70 ft. tall sculpted guitar assembled from industrial waste material by 150 students working continuously for 22 days. Currently, ITI-B has an enrolment of 3,693 students including 276 women enrolled in its one and two-year diploma programmes covering 26 trades such as fitter, turner, machinist and marine engine fitter. Last year, the institute recorded 1,848 placements with graduates placed in Suzuki Motors, Honeywell Turbo, BSNL, and Hero Moto Corp at an average annual remuneration of Rs.1.2 lakh.

ITI-Berhampur is one of the country’s pioneer ITIs. We provide students hands-on training, interdisciplinary learning and curriculums aligned with industry requirements. The problem with most ITIs is that our curriculums aren’t contemporary and training is often on outdated machinery. Under OSDA’s guidance, I am confident that ITI-B will develop into a centre of excellence ready to share best practices and mentor other ITIs,” says Dr. Rajat Kumar Panigrahi, principal of ITI-B and member of the first batch of TVET leaders to train in Singapore.

One of OSDA’s major thrust areas is to increase enrolment of girl children in ITIs and other VET institutions in the state by 30 percent over the next five years. To this end, ITI-B has launched a major students recruitment drive and organised campus visits of secondary/senior secondary girls from the neighbourhood.

This recruitment drive has recorded excellent results with the number of girl students admitted in ITI-B quintupling from 61 in 2016-17 to 300 in 2018-19. And across the state, women enrolments in vocational courses have risen from 6 percent in 2016 to 18 percent currently (the all-India average of women enrolments in the ITIs is 8 percent).

Since it was launched in 2016, OSDA’s primary focus has been on rejuvenating the state’s 49 ITIs and 32 skills development centres (SDCs) which provide vocational education to an aggregate 30,000 students. Among OSDA’s brand-building initiatives is the ‘Skilled in Odisha’ campaign under which all ITIs and SDCs statewide have been directed to display hall of fame and alumni profiles on their notice boards with ‘Skilled in Odisha’ photo-posters of professionals in various trades emblazoned on government buses and in government offices to acknowledge their service to society, and to create VET superstars. Moreover, in 2016, OSDA commissioned the renowned National Institute of Fashion Designing, Bhubaneswar to design hip, trendy uniforms for ITI students.

OSDA’s brand-building campaign and its VET advocacy received an accidental boost after the devastating cyclone Fani hit Odisha on May 3, taking a toll of 64 lives and destroying property valued at Rs.24,000 crore. OSDA mobilised a force of 200 ITI final semester volunteer students to restore and repair public utilities. In groups of six-10, student teams fanned out across Bhubaneswar, the state’s admin capital, and spent a week doing electrical, plumbing and other repair work. This first-of-its-kind initiative of ITI students won the hearts and minds of the public.

Odisha has an ancient tradition and culture of skills and trades education — the coastal district of Kendrapara has a record of sending out 100,000 plumbers to work in other states of India and abroad. Moreover, an estimated 50 percent of women apparel manufacturing workers in the knitwear hub of Tirupur, Tamil Nadu comprises migrant women from this eastern seaboard state because of insufficient employment opportunities at home.

Building the OSDA brand and crafting public campaigns to popularise VET apart, the authority is also focused on infrastructure and curriculum upgradation of ITIs. All 58 trades offered by the 49 government ITIs are compliant with NSQF (National Skills Qualifications Framework) norms and standards, and the curriculum updated in line with latest industry developments in 2014 by the Directorate General of Training, Delhi with a budget of Rs.80 crore earmarked for infrastructure development including procurement of new plant and machinery required for NSQF compliance. Importantly, digital literacy, soft and life skills training have been added to the ITI curriculum.

Moreover, the Delhi-based Tata Strive of the Tata Community Initiative Trust has been signed up as a partner to design and deliver communication and life skills programmes. “Technical proficiency per se cannot guarantee success in 21st-century workplaces. The soft skills of collaboration, teamwork, and communication are equally important. The Tata Strive curriculum is specially designed to develop these life skills of VET students through experiential learning. We have also introduced modules on sustainability, safety, total quality management, design thinking, study of job roles, and information on job fairs and exhibitions,” says Sanjogita Mishra, senior manager, special projects (Odisha) of Tata Strive.

Moreover, the Delhi-based Tata Strive of the Tata Community Initiative Trust has been signed up as a partner to design and deliver communication and life skills programmes. “Technical proficiency per se cannot guarantee success in 21st-century workplaces. The soft skills of collaboration, teamwork, and communication are equally important. The Tata Strive curriculum is specially designed to develop these life skills of VET students through experiential learning. We have also introduced modules on sustainability, safety, total quality management, design thinking, study of job roles, and information on job fairs and exhibitions,” says Sanjogita Mishra, senior manager, special projects (Odisha) of Tata Strive.

With the programme for rejuvenating ITIs progressing smoothly, Bagchi has set his sights on enabling the state’s 350 privately promoted technical education institutions to follow suit and upgrade academic standards and infrastructure. Moreover, the state government plans to establish 23 new ITIs in the next one-two years. Parallelly, the first Advance Skill Training Institute (ASTI) is nearing completion in Bhubaneswar and will admit its first batch of students in July this year.

This first-of-its-type ASTI in the country, will operate from a modern 18-storey building housing OSDA’s World Skill Centre (WSC). This futuristic building was purchased from the Odisha Industrial Infrastructure Development Corporation (IDCO) for Rs.140 crore in 2019.

This first-of-its-type ASTI in the country, will operate from a modern 18-storey building housing OSDA’s World Skill Centre (WSC). This futuristic building was purchased from the Odisha Industrial Infrastructure Development Corporation (IDCO) for Rs.140 crore in 2019.

ASTI, established in PPP (public-private partnership) mode with financial support from the Asian Development Bank, will provide training in eight futuristic skills/trades ranging from transportation to hair styling. Spread over eight floors, ASTI will initially be managed by ITES, Singapore for two years, and offer state-of-the-art infrastructure including live industry-size training workshops and laboratories.

“This investment in a thoroughly modern WSC will go a long way in making skills education aspirational and motivate the best and brightest youth to sign up for VET programmes,” predicts Sanjay Kumar Singh, commissioner-cum-secretary of the Skill Development & Technical Education department of the Odisha government.

The BJD government’s push to change public perception and mindsets about VET is important because traditionally, skills education has been accorded low status in the education continuum and associated with under-paid blue collar jobs. Decades of government neglect of VET — there are a mere 11,800 vocational education centres in India cf. 300,000 in China — has reinforced public, parental and student indifference to VET. Therefore, OSDA has made a signal contribution to India Inc by giving VET an image makeover.

Among the authority’s most prominent and popular student motivation initiatives is a programme to encourage and train students of ITIs and professional engineering colleges for participation in the annual WorldSkills Competition (WSC). Started in 1950, this prestigious biennial competition (aka World Championships of Vocational Skills) organised by the Madrid-based WorldSkills Foundation, attracts youth from industry, government and education institutions of its 79 member countries.

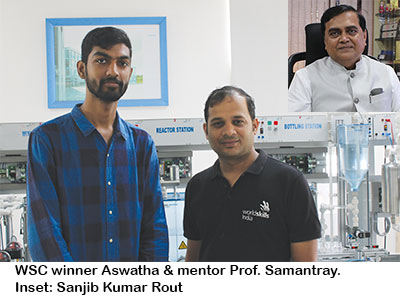

Last August, in the 45th biennial edition of WSC held in Kazan (Russia), Odisha’s Aswatha Narayana, an alumnus of Bhubaneswar’s C.V. Raman College of Engineering, created history by becoming the first Indian to win a gold medal in the water technologies management category. In the preceding national qualifying competition, Odisha bagged 21 medals, second only to Maharashtra with 23. The state government has awarded a cash prize of Rs.10 lakh to Aswatha and Rs.5 lakh to his mentor Prof. Rajat Kumar Samantray. Earlier, the Odisha government had conferred a Rs.5 crore grant to the private C.V. Raman College of Engineering to train students including Aswatha, for WSC 2019.

Sanjib Kumar Rout, chairman of the C.V. Raman College of Engineering (estb.1997), credits OSDA and its no-strings-attached grant of Rs.5 crore to the college for Aswatha’s WSC success. “The generous government grant helped us to invest in the professional training of students for the WorldSkills competition. Enthusiasm generated by  this global competition has created an education ecosystem in which continuous curriculum updation, practical training, research and industry linkages are top priority. Moreover, it has enabled us to become internationally recognised and attracted the interest of several European and Russian companies who want to set up labs on our campus,” says Rout.

this global competition has created an education ecosystem in which continuous curriculum updation, practical training, research and industry linkages are top priority. Moreover, it has enabled us to become internationally recognised and attracted the interest of several European and Russian companies who want to set up labs on our campus,” says Rout.

Indeed, the awards and encomiums won by Odisha’s VET students in WSC — the ‘olympics’ of skills education — has boosted youth interest in vocational education. Last year, OSDA received 5,000 applications from youth to compete in district-level elimination rounds. This year OSDA expects 20,000.

However, OSDA’s most ambitious initiative is to link VET with entrepreneurship by attracting philanthropic capital. In 2017, OSDA launched its ‘Nano Unicorns’ pilot programme under which 204 graduates identified by heads of ITIs and SDCs were provided training in business plan development, marketing and other business skills and given a one-year interest-free loan of upto Rs.1 lakh to promote start-ups. The Centre for Youth and Social Development (CYSD), a Bhubaneswar-based citizens group, and Tata Strive have been co-opted to manage this scheme which has accumulated a corpus fund of Rs.2 crore generated from donors. CYSD’s target is to seed 3,000 Nano Unicorns by 2022.

Comments Jagannanda, co-founder of CYSD and former chief information commissioner of Odisha: “The objective of the Nano Unicorns programme is to identify ITI/SDC graduates with entrepreneurial mindsets and enable them to become job creators. Initially, we approached the Union skills development ministry to fund this scheme, but they refused. Eventually, we persuaded a few high net worth individuals to donate and fund this programme. We are confident of creating 3,000 Nano Unicorns over the next two-three years,” he says.

Comments Jagannanda, co-founder of CYSD and former chief information commissioner of Odisha: “The objective of the Nano Unicorns programme is to identify ITI/SDC graduates with entrepreneurial mindsets and enable them to become job creators. Initially, we approached the Union skills development ministry to fund this scheme, but they refused. Eventually, we persuaded a few high net worth individuals to donate and fund this programme. We are confident of creating 3,000 Nano Unicorns over the next two-three years,” he says.

On the ground, this micro-entrepreneurship scheme monitored by Geetanjali Mishra, retired general manager of the State Bank of India who was persuaded by Bagchi to sign up as consultant with OSDA in 2017, has already produced impressive results. Your correspondent interacted with four women entrepreneurs in Bhubaneswar, who extolled CYSD for giving them the much-needed impetus to launch on their own. “I always wanted to study textile engineering but couldn’t afford it, so I enrolled in an ITI for a diploma in textile design. During my final semester, I met Ms. Geetanjali who had visited our college to brief us about Nano Unicorns. I was selected and with the Rs.1 lakh loan, I have rented a small shop and am working with part-time artisans. My dream is to establish my own design label and employ 3,000 people soon,” says Kamini Kanchan Sahoo (23).

The other three women who have benefited from the Nano Unicorns scheme are Gayatri Naik, a single mother of three, and Sumitra Naik, former captain of the national women’s Rugby team. Both of them have promoted beauty parlours. Swapnamayee Samantra, an ITI graduate in dress design, has established a tailoring unit in Khurda village on the outskirts of Bhubaneswar.

The other three women who have benefited from the Nano Unicorns scheme are Gayatri Naik, a single mother of three, and Sumitra Naik, former captain of the national women’s Rugby team. Both of them have promoted beauty parlours. Swapnamayee Samantra, an ITI graduate in dress design, has established a tailoring unit in Khurda village on the outskirts of Bhubaneswar.

A notable feature of the Odisha government’s skills education initiatives is introducing VET in school education. In a first-of-its-type initiative in 2017, VET programmes were introduced in 44 government higher secondary schools under the government’s Vocationalisation of Secondary and Higher Secondary Education programme. Currently 314 secondary schools are being covered under the programme with students receiving basic training in IT and ITES, retail, travel and tourism, banking, financial services and insurance, beauty and wellness and healthcare.

With the VET-in-school programme enthusiastically welcomed by student and parent communities, the state government has drawn up a blueprint to also include it in 314 schools proposed to be promoted by the Odisha Adarsha Vidyalaya Sangathan (OAVS).

Launched in 2015, the objective of OAVS is to establish English-medium CBSE-affiliated class VI-XII co-educational schools in all of the state’s 314 rural and semi-rural administrative blocks. Thus far, 190 OAVs have been established with an enrolment of 60,000 students. Modelled on the highly successful 661 Central government-promoted Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalayas — free-of-charge boarding schools for meritorious rural students — OAVs, though currently co-ed day schools, will provide residential accommodation in due course.

Launched in 2015, the objective of OAVS is to establish English-medium CBSE-affiliated class VI-XII co-educational schools in all of the state’s 314 rural and semi-rural administrative blocks. Thus far, 190 OAVs have been established with an enrolment of 60,000 students. Modelled on the highly successful 661 Central government-promoted Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalayas — free-of-charge boarding schools for meritorious rural students — OAVs, though currently co-ed day schools, will provide residential accommodation in due course.

According to Dr. Bijaya Kumar Sahoo, advisor-cum-working president of OAVS and promoter-chairman of the top-ranked SAI International School, Bhubaneswar, these model schools “will not only deliver high- quality academic education, they will also integrate skills education in classes IX-XII”. “Our schools will offer all the vocational courses of CBSE and provide state-of-the-art laboratories and technical workshops,” he promises.

While monitors of Odisha’s buzzing skills education scene are appreciative of the government’s efforts to overhaul VET in the state, they believe the scale of the challenge is huge and the focus needs to go beyond the 49 government ITIs, skill development centres and secondary schools to include private VET providers and higher education  institutions. “Public awareness about the importance of skills education has undoubtedly increased because of the state government’s initiatives. But because historically, VET has been accorded second class status by society, the impact of these initiatives and OSDA is limited. The government needs to move beyond the ITIs and focus on educating school teachers about the benefits of skills education and start summer schools for skills training. Most important, vocational education should be a mandatory part of mainstream school and higher education systems with children given pathways for entry into full-time VET programmes. Simultaneously, we need to create a cadre of high-quality VET trainers and educators. Currently, skills development initiatives are focused on government institutes while private VET providers are tightly regulated. Private institutes need to be incentivised and integrated into this skills upgradation drive,” says Dr. Mukti Mishra, a nationally respected VET leader and president of Centurion University, Bhubaneswar (estb.2010), a top-ranked private professional education varsity which also hosts a School of Vocation providing short-term certificate courses and diploma programmes for learning blue-collar industry-oriented skills (fitter, welder, electrician, CNC operator, auto service technician etc).

institutions. “Public awareness about the importance of skills education has undoubtedly increased because of the state government’s initiatives. But because historically, VET has been accorded second class status by society, the impact of these initiatives and OSDA is limited. The government needs to move beyond the ITIs and focus on educating school teachers about the benefits of skills education and start summer schools for skills training. Most important, vocational education should be a mandatory part of mainstream school and higher education systems with children given pathways for entry into full-time VET programmes. Simultaneously, we need to create a cadre of high-quality VET trainers and educators. Currently, skills development initiatives are focused on government institutes while private VET providers are tightly regulated. Private institutes need to be incentivised and integrated into this skills upgradation drive,” says Dr. Mukti Mishra, a nationally respected VET leader and president of Centurion University, Bhubaneswar (estb.2010), a top-ranked private professional education varsity which also hosts a School of Vocation providing short-term certificate courses and diploma programmes for learning blue-collar industry-oriented skills (fitter, welder, electrician, CNC operator, auto service technician etc).

The OSDA team is well aware that the state’s 49 ITIs and other formal VET centres have a capacity to admit only 60,000 students annually, and are unable to accommodate the 265,000 children who drop out after classes X and XII statewide. Therefore, it has begun to aggressively focus on providing short-term skilling programmes for youth in the 15-35 years age group under the Central government’s DDU-GKY (Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameen Kaushalya Yojana) and PMKVY (Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana) schemes and has also started its own short-term courses. To enable delivery of these short-term (three-six month) programmes, OSDA has established skill development centres (SDCs) in all of the state’s 30 districts.

These SDCs are well-equipped with modern classrooms, laboratories, training workshops and also provide hostel facilities. They serve as training centres for both private VET providers operating under the Central government’s National Skill Development Corporation and OSDA’s placement linked training programs (PLTP). “Though we tightly monitor the implementation of Central government schemes in our SDCs, we felt the need to devise our own placement linked training programs. PLTP programmes are very popular because we provide free accommodation and training followed by a three-month stipend after students graduate,” says Phalguni Nayak, a nodal officer with OSDA.

Undoubtedly chief minister Naveen Patnaik, the Odisha government and OSDA have combined to blaze a new trail to transform the hitherto educationally backward state into a VET leader. Its ITIs upgradation drive, well-equipped Skills Development Centres operational in the state’s 30 districts, entrepreneurship development programmes, introduction of VET in senior schools and most importantly VET brand-building public campaigns, have conferred skills education social respectability. Subroto Bagchi, who has conceptualised and implemented these revolutionary industry-friendly initiatives, is confident OSDA will quickly scale up all its programmes and positively impact youth employability and the state’s economy.

“OSDA’s target to skill 1.5 million youth in the next five years is well on its way to realisation. Meanwhile, we are also improving quality of ITI education and adding more short-term skills development courses. Admittedly, there are challenges, especially the problem of poor social acceptance of skills education, shortage of quality skills trainers, training partners and tepid industry response. But fortunately we have the full support of the state government and are determined to make Odisha the epicentre of the country’s belated VET and skills education drive,” says Bagchi.

It’s a consummation devoutly to be wished.

OSDA’s quick start

Estb. 2016 by Odisha state government

Chairman: Subroto Bagchi

Major objectives: Provide direction to all government skill development initiatives, harmonise efforts of government and private agencies, develop Odisha into a global destination for employers of skilled workers, and to create replicable models of skills education.

Target: Comprehensive skilling of 1.5 million youth by 2024

Milestones

• In 2017, OSDA signed an MoU with ITES, Singapore (Institute of Technical Education) to train principals/vice principals/senior faculty of the state’s 49 ITIs. Thus far, 100 ITI faculty have visited Singapore for two-week leadership development programmes

• OSDA has developed 32 skill development centres (SDCs) and 38 skill development extension centres to provide 39 short-term placement linked training programmes

• Skills training is offered in 196 trades by the ITIs and SDCs

• In 2017, the Nano Unicorn scheme was launched to foster micro entrepreneurship within ITI/SDC graduates. Thus far, 204 entrepreneurs have graduated from this programme

• In August 2018, a Skill Museum at Government ITI, Cuttack, a first-of-its-genre in India, was inaugurated by chief minister Naveen Patnaik

• Students from Odisha won 21 medals at the IndiaSkills 2018, India’s largest skills competition held in Delhi last October. It’s ranked #2 in the medals tally, behind Maharashtra with 23 medals

• OSDA is setting up eight Advanced Skill Training Institutes (ASTIs) in public-private-partnership mode with financial support from the Asian Development Bank. The first ASTI is set to admit its first batch of students in July 2020.

Draft NEP 2019 vocational education recommendations

The 484-page National Education Policy (NEP) Draft 2019 of the nine-member Kasturirangan Committee — whose major recommendations are likely to be accepted and included in the final NEP expected to be released by the Union HRD ministry anytime now — accords high priority to VET. It strongly recommends integration of vocational training into mainstream education in schools, colleges and universities, and sets government a target of “providing vocational education to at least 50 percent of all learners by 2025”. Excerpts:

• Vocational education must not be developed separately from ‘mainstream’ education. It must be fully integrated within mainstream education so that all students are exposed to vocational education and have the choice to pursue specific streams of vocational education. There must also be easy mobility across vocational and general academic streams, through clear equivalence of qualifications/certifications and credit structures.

• The National Policy on Skills Development and Entrepreneurship (NPSDE) announced in 2015 specified that 25 percent of educational institutions should offer vocational education. We make a major departure from this policy to specify that not just 25 percent, but all educational institutions — schools, colleges and universities — must integrate vocational education programmes in a phased manner. All school students must receive vocational education in at least one vocation in grades 9-12.

• HEIs (higher education institutions) will also offer vocational courses that are integrated into the undergraduate education programmes, with course content that combines adequate hands-on experience with the requisite theoretical background, delivered within a general education setting. However, there are many short term challenges given the involvement of many ministries and numerous other stakeholders in the provision of vocational education currently. A separate National Committee for the Integration of Vocational Education (NCIVE) will need to be set up, consisting of members from across ministries, to review the long term goals outlined here and to work out the steps that need to be taken towards achieving them.

In order to operationalise this fresh approach to vocational education, the policy envisages the following:

• Relevant and meaningful integration of vocational education into school and higher education through skills analysis and mapping of local opportunities.

• Network of ministries, bodies/agencies and institutions as well as local industries and individuals.

• Adequate investment in developing infrastructure, as well as recruiting, preparing and supporting individuals to transact vocational education effectively.

• Maintenance of databases and study of possible models of vocational education which can be applied in our context.

• Ensuring mobility of learners across institutions and streams, through alignment with international standards, and curricula and assessment aligned to the NHEQF (National Higher Education Qualification Framework) and NSQF (National Skills Qualifications Framework).

• Enhanced capacity of vocational education particularly at the higher education stage, and in rural and tribal areas.

• Integration of work of local craftspersons and artisans into the curriculum, along with measures to disseminate their work more widely.

“Good quality housing needed for skilled workers”

Autar Nehru interviewed Subroto Bagchi, chairman of the Odisha Skill Development Authority (estb. 2016) in Bhubaneswar. Excerpts:

How satisfied are you with the growth and development of OSDA?

How satisfied are you with the growth and development of OSDA?

When I wake up in the morning, I tell myself that there is so much to be done. Skill is an intergenerational issue. The people whose lives we’re touching haven’t been touched by governments for centuries. A massive percentage of the population was ignored by the State from developing inherited and industrial age skills. Thus, what we have started and may have achieved, is a drop in the ocean. The children and youth we have skilled in Odisha have many generations of development to catch up on, to be on a par with their counterparts in developed OECD countries. In Odisha, we can take some credit for consolidating and aligning the efforts of the government, bureaucracy and education system. Therefore, to answer your question, we have reasons to be happy but so much more to get done.

VET has suffered government neglect for decades, and despite recent government initiatives such as NSDC, Skill India, it hasn’t taken off. What is your prescription for boosting VET countrywide?

I look at my job as not to theorise but to focus on what is working. Indians criticise too much. I don’t worry about things outside my control. I prefer not to blame policy, do what I can do myself. Today, there are a plethora of government schemes with generous allocations. But, there is one issue which nobody is talking about: safe and good quality housing for skilled workers. If we don’t address this problem, the skills story will only go thus far. We can’t merely skill people and not address what happens after that.

Most skilled workers migrate to cities for jobs and are forced to live in slums. This isn’t likely to make skills education aspirational among youth. Also, wage disparities are abysmal. Compared to workers — skilled or otherwise — in developed countries, Indian workers are very poorly paid. The State, private sector, everyone likes to keep it that way. We are an exploitative society when it comes to people at the bottom of the pyramid.

The Draft National Education Policy 2019 has recommended integration of VET in mainstream education — schools, colleges and higher ed institutions. How aligned are OSDA’s initiatives with the Draft NEP’s recommendations?

We are continuously looking for new ideas and are working on formulating a new Skill Vision 2024 for Odisha. We will surely draw upon NEP 2019 for ideas.

What are OSDA’s future plans?

Our mandate is to deliver skills education and training to 1.5 million youth during the period 2019-2024, an achievable target. We also intend to quickly get the World Skill Centre off the ground, win more laurels at the World Skills Competition, attract high-quality employers to Odisha and scale up our Nano Unicorn entrepreneurs programme. We want Odisha to be a sandbox of innovation in the skills sector, and are preparing a Skill Vision 2024 that will draw on the UN Sustainable Development Goals 2030. In addition, we are monitoring how the world will change between now and 2024 so we can work in a future-backwards manner to create more future-ready VET programmes for employment and entrepreneurship.

With Summiya Yasmeen