Winds of change reminiscent of the 1991 Union budget that catalysed liberalisation and deregulation of industry, are gathering momentum in India’s moribund education sector mired in dead habit, rote learning and rock-bottom learning outcomes writes Dilip Thakore

You cant read further without a subscription. If already a subscriber please Login or to subscribe click here

Three decades after the watershed Union Budget of 1991 catalysed liberalisation and deregulation of Indian industry, doubled post-independence India’s annual rate of economic growth which averaged 3.5 percent (“the Hindu rate of growth” in the famous disparagement of late economist Dr. Raj Krishna), and lifted 400 million citizens out of poverty, similar winds of change are gathering momentum in India’s moribund education sector mired in dead habit, rote learning and rock-bottom learning outcomes.

A strong, accelerating reforms current is coursing through the shady bowers and musty corridors of the country’s 200,000 pre-primaries, 1.4 million primary-secondary schools, 42,000 colleges and 1,072 universities with an aggregate enrolment of 300 million children and youth. Suddenly after decades of masterly inactivity, dozens of new genre private schools, colleges and universities providing world-class infrastructure, highly qualified faculty drawn from around the world, are dispensing contemporary syllabuses and curriculums to children of the country’s fast T expanding middle class, if not yet to unfortunate children of bottom-of-pyramid households.

Since the dawn of the new millennium, 44 continuum (K-12) schools affiliated with the Geneva/The Hague-based International Baccalaureate and 400 schools affiliated with the UK-based Cambridge Assessment International Education (CAIE) boards which prescribe globally respected syllabuses, curricula and certification, have become operational in India. And some of Britain’s most famous public (i.e, private, exclusive) schools including Millfield, Wellington and Harrow (alma mater of Jawaharlal Nehru and Winston Churchill) are readying to plant their flags in Indian terra firma this year.

These venerated schools which pride themselves on delivering excellent mix of academic, co-curricular, sports and life skills education, and especially for nurturing students’ leadership skills, hold out promise of churning out industry, business and professional leaders who could lead India’s charge towards transforming into a $30 trillion (from the current $2.9 trillion) economy by 2047, when the nation celebrates the centenary of its independence from debilitating foreign (British) rule.

“With the National Education Policy 2020 directing education in India towards key principles and strategies associated with internationally accepted teaching-learning norms, international schools are becoming increasingly popular within the country. We have witnessed strong demand for overseas curricula in recent years which for instance, has made International Baccalaureate certification highly desired and respected. A recent UGC guidelines draft has brought greater clarity about rules and regulations governing foreign higher education institutions aspiring to become operational in India. We hope this will lead to more reforms and transparency in K-12 education, especially on the issue of international organisations and schools becoming active in India,” says Samuel Fraser, a social sciences graduate of Kingston University (UK), a former banker with education management and research experience in Bahrain, Singapore, Kazakhstan, and currently the Mumbai-based Director (India) of ISC Research Ltd. ISCR which has its head office in Oxford (UK), provides data and information related to improvement, development and acquisition to 13,192 English-medium international schools with 6.5 million students worldwide.

Fraser is optimistic because in a landmark departure from post-independence India’s isolationist, insular, socialist ideology, the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, presented to the nation after a hiatus of 34 years, encourages internationalisation of higher education. It mandates government and privately promoted colleges and universities across the country to reach out and connect with counterparts overseas. However, it’s noteworthy that the internationalisation of Indian higher education had already begun prior to finalisation of NEP 2020. In the new millennium, several globally benchmarked American Ivy league-inspired private liberal arts universities notably Amity (2003), Jindal Global (estb.2009), Ashoka (2014), Krea (2018) and a handful of science and technology varsities including Shoolini (2009), Chitkara (2010) and Shiv Nadar (2011) among others, have sprung up across the country catalysing “a sea change in higher education” (see EW cover feature https://www.educationworld.in/private-varsities[1]catalysig-sea-change-in-higher-education/).

Liberalisation of India’s higher education system dominated by 54 well-funded Central government universities and 460 relatively under-funded state government universities with 42,000 affiliated colleges that provide low grade undergrad education, has reportedly been spurred by prime minister Narendra Modi and Union education minister Dharmendra Pradhan. They have risked displeasure of the RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh) — the ideological mentor organisation of the BJP — by greenlighting liberalisation of the education sector in the broader national interest. Moreover special legislation has been enacted several state governments to establish greenfield private universities and international schools within their jurisdiction. Somewhat belatedly, state governments have discovered that education is a ‘concurrent’ subject under the Constitution of India, and therefore they are empowered to sanction private education institutions within their boundaries.

This flurry of capacity-building across the spectrum in India’s lackadaisical education sector has generated considerable expectation within academia and society that Indian education is at an inflection point and is poised to experience a 1991 moment, when post-independence India’s elaborate industrial licensing regimen which shackled business and industry for over 40 years, was substantially dismantled in the historic Union Budget of that year formulated by the Narasimha Rao-led Congress government. However, experienced professionals monitoring Indian education believe the upgradation, reform and expansion of capacity being witnessed currently in the knowledge sector is being driven by the growth of the middle class and incremental social awareness that high quality education is the best passport to upward mobility, rather than NEP 2020 and government initiatives.

Unlike the 1991 industry and commerce liberalisation, large numbers of private universities and schools springing up countrywide is not the outcome of new or changed government policies. They are the consequence of rising awareness within government and society especially in the states, of India’s growing unemployment problem. The government policy framework — that schools, colleges and universities must be not-for-profit institutions promoted under the Societies Act, 1860, the Charitable and Religious Trusts Act, 1920 or as not-for-profit companies under s.25 of the Companies Act, 2013 remains unchanged. But with the country’s GER (gross enrolment ratio) in higher education stuck under 30 percent as against 60- 80 percent in developed OECD countries, progressive state governments in Haryana, Karnataka, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh have enacted enabling legislation for promotion of globally benchmarked private universities to nurture skilled and readily employable graduates. For instance, 25 modern private universities have been established in Haryana in the new millennium. This trend is likely to be spurred by the liberal provisions of NEP 2020,” says Anand Prakash Mishra, a law postgrad of Delhi University and currently Dean and Director, Jindal Global Law School (JGLS) of the privately promoted O.P. Jindal Global University (JGU, estb.2009). In quick time, JGLS has emerged as the country’s largest and most admired fully-residential law school (5,048 students mentored by 487 faculty).

Unsurprisingly, liberalisation and in particular entry of branded foreign schools and universities is anathema to leftists and socialists who despite the collapse of communist ideology and regimes worldwide continue to dominate Indian academia. For this lobby, issues of equity and inclusion of historically marginalised communities and EWS (economically weaker sections) are of greater import than transformation of higher education institutions (HEIs) into globally competitive centres of learning and research.

“Twenty-first century India is already one of the most unequal societies worldwide. According to a recent Oxfam report, the rich 1 percent own 50 percent of national wealth and top 10 percent owns 80 percent of national assets and wealth. Liberalisation of the education sector to permit multiplication of private schools and universities charging monthly tuition fees which are ten-twenty times the average annual household income, is licence to perpetuate the existing inegalitarian social order and generate social tension. Moreover, import of western syllabuses and curriculums will dilute, if not extinguish, Indian culture and traditions of a large number of schools and universities whose graduates will be further alienated from the general population,” warns the education professor of a top-ranked Central university who preferred to remain anonymous.

Rohit Dhankar, professor at the Azim Premji University, Bengaluru (estb.2010), ranked India’s #1 private university for social sciences in the EW India Higher Education Rankings 2022-2023, is also unenthused about the red carpet rolled out by NEP 2020 and UGC (University Grants Commission) for foreign education institutions, and universities in particular. “Every nation has its own distinctive cultural consciousness and world-view. India’s deepest thinkers and intellectuals Sri Aurobindo and Rabindranath Tagore envisioned the university as a deep well and centre of history and culture rooted in the Indian context from which knowledge, ideas and innovations relating to teaching the social sciences, art and literature in particular would emerge. The entry of foreign universities will provide further impetus to the process of grafting alien cultural-consciousness and world-view on to our higher education institutions. This process which began during the British Raj remained uncorrected after independence. As a result, our higher education system has failed miserably and our cultural consciousness has substantially di[1]minished, force-fitted into social theories developed to understand a different cultural milieu. A large number of foreign, especially British schools and universities, setting standards and benchmarks in Indian education will result in completion of Lord Macau[1]lay’s agenda of transforming middle class Indians into second class Englishmen, resulting in schizophrenic moral codes and jingoistic nationalism for self-assertion,” warns Dhankar.

Although there’s some merit in the argument that conceding a larger role to the private sector in school and higher education is likely to exacerbate inequalities in Indian education and society, it’s pertinent to acknowledge that a great divide between rich and poor children has been a notable feature of Indian education for several decades, especially in K-12 education. It’s hardly a national secret that post-independence India’s great middle class — estimated at 300 million — has almost entirely been educated in fees levying private schools whose number is currently estimated at 450,000 countrywide. This is because the country’s 1 million government schools — mostly owned and managed by state governments — are distinguished by crumbling buildings, chronic teacher truancy, multigrade classrooms, lack of toilets, and aversion to teaching English. They are in such poor condition that only bottom-of-pyramid households enrol their children with them, mainly because of their free-of-charge mid-day meal rather than free tuition.

Therefore, the solution to reduce inequalities in education is not prohibition and/or proscription of private schools, but improving infrastructure and sharply raising teaching-learning standards of government schools. Likewise, designing indigenous syllabuses and curriculums rooted in Indian history and culture has defied the ingenuity of left and left-liberal professors and pundits who have dominated the academy, for over seven decades.

Meanwhile, the authoritative Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) surveys of the Delhi/Mumbai-based Pratham Education Foundation of the past 25 years are a sad commentary on the quality of education in government schools. In 616 (out of a total 730) districts countrywide, learning outcomes of children in primary/elementary education are going from bad to worse. According to ASER 2022, in rural India (which grudgingly hosts 60 percent of the population) over 50 percent of class V children can’t read and/or comprehend class III texts, and manage simple math sums.

Although it’s doubtful whether Ivy league American universities which government expects to establish campuses in India will actually do so, liberalisation of rules and regulations relating to the entry of foreign universities into India is a welcome development. Provided that all the freedoms to design their syllabuses and curriculums, and determine tuition fees are also given to India’s private universities, to create a level playing field. The pressure of foreign competition will compel our institutions to raise academic and research standards, which is in the national interest. In the K-12 sector, the high fees that international schools will surely charge shouldn’t be a matter of public concern because only the top 1 percent households will be attracted to them. According to a Private Schools in India Report 2020 conducted by CSF, over 70 percent of India’s private schools levy tuition fees of less than Rs.1,000 per month. The uniqueness of India’s private education sector is that it offers relatively good quality K-12 education at every price point. Therefore, there’s no need to fear or impose regulatory ceilings on private, including foreign schools,” opines Ashish Dhawan, promoter chairman of the Delhi-based Central Square Foundation (CSF), who orchestrated the crowd-funding of India’s high ranked Ashoka University (2014), and is currently promoter chairman of CSF, registered in 2016 with an endowment of Rs.50 crore.

Although no dramatic legislation on the lines of the Union Budget of 1991 which in one stroke abolished the industrial licensing and monopolies laws, has been passed by the Centre or any state government, the steady, below-the-radar liberalisation and deregulation of Indian education, especially the low-profile entry of international school management chains and imminent entry of foreign universities has enthused perceptive monitors of India education. Rakesh Gupta, a highly qualified alum of IIT-Kharagpur and the blue-chip Indian School of Business, Hyderabad, former consultant with the US-based multinational consultancy, McKinsey & Co and currently promoter-director of LoEstro Advisors Llp, a Hyderabad-based investment banking and consultancy firm, believes “an improved democratic policy framework” has emerged in Indian education.

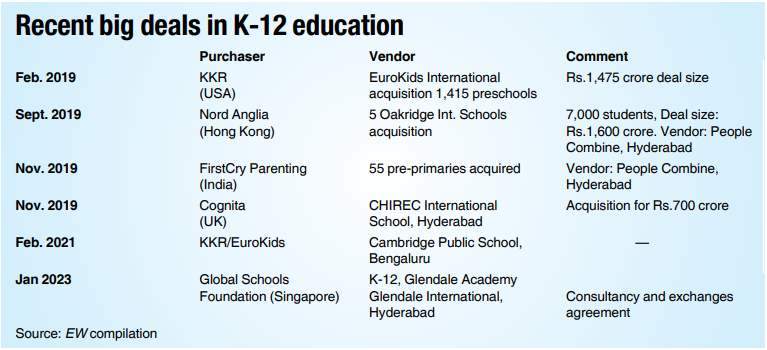

“Currently there is a global movement towards consolidation in K-12 education. Several large corporates such as Cognita and Nord Anglia (UK), Inspired (South Africa) and Global Schools Foundation (Singapore) have allied with education entrepreneurs in developing countries to establish high quality, globally benchmarked schools. In the first decade of the new millennium, these companies enabled the promotion of school chains such as Oakridge, Pathways, Orchid and GIIS in India. Subsequently, there was a lull in the entry of foreign education companies and brands following a period of policy confusion about the powers of state governments to regulate tuition fees. Since then in recent years, this confusion has been substantially cleared up with most state governments restricting themselves to regulating tuition fee increases, rather than tuition fees per se. This makes sense as parents admit their children into a school after ascertaining tuition and other fees. However, it’s quite right that they shouldn’t experience the shock of huge fee hikes. In recent times, most state governments have enacted legislation to control tuition fee increases rather than tuition fees, prescribing differing formulae. Annual fee increases have been restricted to 10-12 percent in most states and in Uttar Pradesh to official inflation plus 5 percent. This read with the liberal provisions of NEP 2020 has introduced policy stability and encouraged domestic and foreign private investment in K-12 education. Moreover, the entry of international schools and educationists is also certain to raise teaching-learning standards towards global levels,” says Gupta.

Although several deep-thinking educationists and academics entertain misgivings about the entry of foreign schools and universities with long colonial histories into the Indian education marketplace, if the credits and debits of liberalisation are weighed, there’s no doubt the former outnumber the latter. Apprehensions relating to exacerbation of social inequality and cultural diminution are abstract considerations that require total restructuring of the education system. On the other hand, the urgent priority of government and society is to upgrade the preschool to Ph D education system immediately, to ensure that the world’s largest child and youth population has access to high quality globally comparable teaching learning for the country to encash its much-proclaimed demographic dividend before it lapses.

Intelligent monitors of contemporary India’s floundering education system are becoming increasingly apprehensive that with primary secondary education still mired in rote learning and memorisation, and higher ed institutions over-reliant on received wisdom, unless there’s urgent reform and upgradation of the education system, there’s clear and present danger of the overdue demographic dividend transforming into a massive demographic liability as the vast majority of 10 million ill-educated and unskilled unemployable — rather than unemployed — youth entering the jobs market every year, scour the country searching for meaningful employment.

Therefore even if belatedly, pressing urgency to reform and contemporise school and higher education has become widespread within the country’s hitherto isolationist teachers and academic communities. Since EducationWorld was launched on the eve of the new millennium to beam a focused and sustained searchlight on pre-primary to Ph D education with the avowed objective to “build the pressure of public opinion to make education the #1 item on the national agenda”, your editors have witnessed huge and rising enthusiasm within the community of school promoters, principals and teachers — albeit to lesser extent in higher education — to raise teaching-learning standards to global norms.

The EducationWorld annual rating and ranking surveys of preschools, primary-secondaries, colleges and universities under several parameters of education — rather than mere academic excellence — have aroused great appreciation within the educators and parents communities. As a result, there is unprecedented awareness within the educators, parents and students communities that the country’s education institutions need to move beyond knowledge accumulation to developing the analytical, critical thinking and problem-solving skills of children and youth to prepare them for the increasingly complex and new technologies-intensive workplaces of the future.

Further evidence of this new awareness of the importance of contemporary syllabuses and curriculums that promote holistic education is provided by the tremendous response that the pioneer annual EducationWorld India School Rankings — which since they were introduced in 2007 have ballooned into the largest and most comprehensive schools ranking survey worldwide — and the follow-up annual EWISR Awards generate within the educators community. Ditto the annual EW preschools, budget private schools, higher education institutions (HEIs) rankings and awards.

In this connection, it’s pertinent to note that unlike institution rankings abroad which rate and rank education institutions under the sole parameter of learning outcomes, the multidimensional EW institutional ranking surveys evaluate schools and HEIs under numerous parameters of excellence including teacher welfare and development, leadership, individual attention to students, curriculum & pedagogy (digital readiness), co-curricular and sports education, safety & hygiene, mental and emotional well-being services, among others.

The importance of balanced, multidisciplinary education is endorsed by NEP 2020. Although there is some legitimate apprehension about over-regulation, this charter unequivocally mandates professionally-administered early childhood and foundational education; development of children’s critical thinking and analytical skills through projects-based and skilling pedagogies; intensive teacher development programmes and incorporation of new-age digital technologies into K-12 education. In higher education, NEP has mandated internationalisation of HEIs through intensified collaboration, student and faculty exchange programmes, and in a remarkable ideological about-turn, it invites foreign universities to establish owned campuses in India.

And it’s a measure of newly developed confidence spreading within the domestic education sector that leaders Cover Story of top-ranked Indian pre-primaries, K-12 schools and HEIs are unperturbed by the prospect of marketplace competition from foreign education institutions. On the contrary, most welcome the entry of foreign schools and universities on the reasoning that their best practices will seep into Indian education, and that competition waves will raise all boats.

“Entry of foreign schools and HEIs into India’s expanding education sector is welcome. I don’t believe they will pose a major threat to the country’s top-ranked international schools which have acquired experience in adapting and innovating best western syllabuses and curriculums for Indian conditions. In our neighbourhood, 25 high quality international schools affiliated with the International Baccalaureate and UK-based Cambridge examination boards have been operational for several years. But they haven’t been able to dislodge us from our #1 rank in your annual EW rankings surveys for the past 11 years. That’s because in Indus International schools, we are constantly improving and enriching the IB curriculum through intensive research and innovation. In 2009 IIS, Bangalore became the country’s first school to establish a teacher training and research institution — ITARI (Indus Training and Research Institute). In ITARI, we train teachers on advanced digitally-enabled simulators, and are conducting research into applying Metaverse, AI and blockchain technologies in education. To develop our technology-enabled curriculum, we have built bridges with higher education institutions including Jindal Global University in India and Soka University, Tokyo. Therefore by continuously upgrading our teachers and developing a hi-tech advanced ecosystem built for Indian conditions, we are confident of taking on the best international schools entering India,” says Lt. Gen. (Retd.) Arjun Ray, PVSM, VSM, chief executive of the Bangalore-based Indus Trust (regstd.2003).

Under Gen. Ray’s leadership, the trust has established four IB-affiliated schools in Bangalore, Pune, Hyderabad and Belagavi with an aggregate enrolment of 3,660 students of 38 nationalities mentored by 450 teachers. And IIS-Bangalore has been ranked India’s #1 international day-cum-boarding school for 11 years consecutively with all other IIS’ ranked within the Top 10 in the annual EWISR surveys.

Be that as it may, with state governments, whose pain point with private and international schools was annual fee increases rather than initial fees, having substantially resolved this is[1]sue and green-lighting the entry of branded international education institutions in their jurisdictions, and NEP 2020 inviting top-rung foreign universities to establish campuses in India, not a few well-informed liberal educationists believe that the 1991 moment has come for Indian education.

“NEP 2020 is a liberation charter that decrees full teaching-learning and research freedom in Indian education. Currently, an estimated 50,000 children and 700,000 youth from India are studying in schools and higher education institutions abroad. Now with the world’s most respected schools and universities granted freedom to establish campuses in India, future generations won’t have to travel abroad for high quality education. I believe the 1991 moment has arrived for Indian education which is poised for full flowering. My only advice to foreign education institutions entering India is to devise scholarship schemes for a small minority to ensure diversity on their campuses. This is good for them and society,” says T.V. Mohandas Pai, the Bengaluru-based former finance director of the blue-chip Infosys Technologies Ltd and chairman of the globe-girdling Manipal Education and Medical Group — India’s largest professional education multinational — and forthright public intellectual.

Nevertheless, although with changed mindsets in government and society, the future seems bright for Indian education and development of India’s abundant and high-potential human resource, it’s prudent to note that while NEP 2020 encourages institutional autonomy and academic freedom, it has also mandated an elaborate multi-layered supervisory structure packed with politicians, bureaucrats and old school educationists, to guide and advise the country’s liberated education institutions. They could yet throw a spanner in the works. Fingers crossed.