India’s prolonged 82 weeks lockdown of schools from pre-primary onward is unprecedented in history. Even during the Spanish flu of 1918-20 which took a toll of 18 million lives, schools did not shut down for more than 20 weeks. Extraordinary challenges require extraordinary response – Summiya Yasmeen

Out-of-school children: grave judgement error

The latest diktats of several state governments, especially the Delhi state government to lock down schools for the fifth time since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic in March 2020, has belatedly provoked public indignation.

Suddenly, hitherto oblivious television news channels, the mainstream print and social media have awoken to the plight of the world’s largest child and youth population (500 million) which has endured 82 weeks of education lockdown — the most prolonged of any country worldwide. Belatedly, the woke middle class is questioning the logic of all other sectors of the economy — industry, trade, travel and tourism, malls, cinemas and restaurants — allowed to resume business while schools remain under tight lockdown.

Although your editors have been strenuously advocating reopening of the nation’s classrooms for over a year, EducationWorld has been a lone voice in the wilderness. Last July in a comprehensive cover feature titled ‘Why Schools Should Reopen Right Now!’ Your editors made a strong case for restarting 1.4 million anganwadis/preschools and 1.5 million schools countrywide.

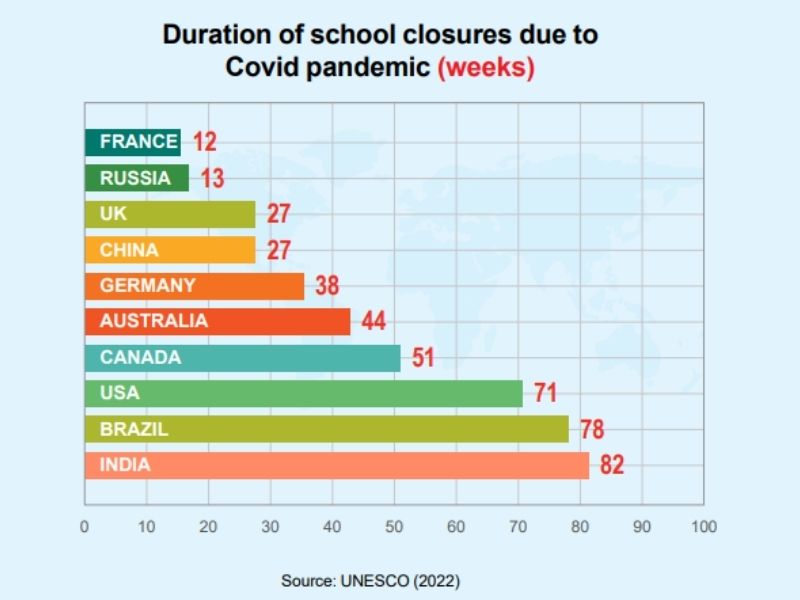

It’s pertinent to note that in India schools have shut down in-class learning for 82 weeks; in worse-hit UK they closed for 27 weeks, 12 in France and 27 in China (see box p.57). Although many countries restarted schools after brief lockdowns, India’s Central and state governments have remained indifferent to the huge learning loss suffered by the country’s vulnerable children. This despite numerous scientific studies highlighting that children are least susceptible to Coronavirus infection (the rate of hospitalisation of school-age children due to Covid infection is 1 in 100,000 — Dr. Joseph Allen, Harvard University) and shuttering schools has negligible effect on limiting the spread of the pandemic (WHO).

Astonishingly, the country’s Central and 29 state governments have remained impervious to numerous studies of international agencies including Unicef and Unesco, which have repeatedly warned against alarming accumulating learning loss of children because of the protracted lockdown of education institutions, especially preschools and primaries. The warning of foreign agencies apart, even studies and surveys of domestic institutions such as Pratham Education Foundation, CRY and Azim Premji University, Bengaluru (APU) have been disregarded.

A substantial share of the blame for this grave national error of judgement must also accrue to the country’s influential middle class which foolishly believes that expensive digital technologies insulate their progeny against learning loss. Simultaneously, for months the mainstream media paid no attention to EducationWorld’s whistle-blowing, which all dailies and periodicals zealously ignore.

Finally on January 4, 700 days after all education institutions countrywide were first ordered to lock down in March 2020, National Coalition on Education Emergency, a pan-India alliance of individuals, organisations and networks, issued a statement censuring government for the prolonged closure of schools and education institutions which has done “serious harm” to India’s 260 million school-going children.

“Schools have recently opened after remaining mostly closed since March 2020, with devastating consequences for the nutrition, health and education of hundreds of thousands of children. Child labour, early marriages, domestic violence have increased. It is evident that the absence of structured learning opportunities has caused severe academic regression, young children have forgotten habits of learning, basic reading and numeracy skills have been affected, and we are seeing huge dropouts as a result. Online education has not been possible or pedagogically meaningful for most children… Keeping schools open is necessary to reduce this serious harm and resume the processes of learning. Schools must be the last to close and the first to open,” thunders the belated statement.

Scandalous neglect of the country’s uncomplaining children forced to learn from cramped, crowded homes — the floor area of the average Indian home is a mere 494 sq. ft and often houses three generations — has compelled even private education providers who tend to tread carefully given the myriad powers of state and local governments to throw a spanner in their works, to speak up.

Mehta: exaggerated phobia

“It’s scandalous that two years into the Covid-19 pandemic, the Central and state governments are sticking with the worn-out strategy of shutting down schools to check its spread. This despite scientific evidence that schools are not super spreaders and that children are as safe or as at risk in school as in malls, restaurants and playing spaces. Pre-primary and primary school children have been out of school for 21 months, with the majority of them unable to afford Internet connectivity and digital devices necessary for online learning. The country’s children have suffered incalculable loss of learning and socio-emotional development. Moreover, by sporadically opening up campuses for class X and XII students, government is sending out the message that board exams are important, not learning. India is experiencing a grave education emergency. State governments need to resist the temptation of shutting schools at the slightest surge in Covid positive cases. Schools should be declared an essential service, ensuring uninterrupted education. It’s a national priority,” says Sumeet Mehta, co-founder and CEO of Leadership Boulevard Pvt. Ltd (LBL, estb.2012), a Mumbai-based company that offers its LEAD schools improvement package to 3,000 partner schools across the country.

The USP (unique sales proposition) of LBL is that unlike most edtech companies that target students for improved academic outcomes, its LEAD programme is an institutional upgradation package for whole school improvement. This USP has impressed investors in education. In December, LEAD became the sixth edtech company to enter India’s unicorn club after it raised $100 million from investors, doubling its valuation to $1.1 billion in less than a year.

Mehta, whose clientele mainly comprises affordable/budget private schools — the sole alternative of low-income households fleeing dysfunctional government schools — is indignant that the resumption of normative schooling debate has been hijacked by “privileged parents who have the recourse of online education”. “The overwhelming majority of children are in government and budget private schools. Their parents want schools to reopen because they are well-aware that their children will be safer in school than in cramped homes and neighbourhoods, and more so because they have very limited access to digital devices and online education in their homes. But because the public debate especially on social media is controlled by upper class parents with great faith in online education, governments are responsive to their exaggerated pandemic phobia. In a democracy, the government’s job is to keep all schools open and leave the choice of sending children to school to parents,” advises Mehta.

Mehta’s contention that there is a class divide on the issue of school reopening is supported by ‘School Children’s Online and Offline Learning (SCHOOL),’ a survey conducted by highly respected sociologist Jean Dreze and development economist Reetika Khera. According to the study released last September, 97 percent of households in rural India want schools to reopen as soon as possible.

The enormity of the academic, socialisation and emotional loss that children have suffered during the most prolonged schools lockdown worldwide, is also beginning to dawn on India’s urban middle class. Urban parents, who were hitherto in the vanguard of citizens demanding schools closure for child health and safety reasons during the first and second waves of the pandemic, are doing serious rethinking. Against the new backdrop of 70 percent of adult citizens including teachers double jabbed, and emerging evidence that the new Omicron variant of the Coronavirus is relatively benign, there’s a rising groundswell of opinion in favour of schools resuming on-campus classes subject to maintenance of safety protocols.

The enormity of the academic, socialisation and emotional loss that children have suffered during the most prolonged schools lockdown worldwide, is also beginning to dawn on India’s urban middle class. Urban parents, who were hitherto in the vanguard of citizens demanding schools closure for child health and safety reasons during the first and second waves of the pandemic, are doing serious rethinking. Against the new backdrop of 70 percent of adult citizens including teachers double jabbed, and emerging evidence that the new Omicron variant of the Coronavirus is relatively benign, there’s a rising groundswell of opinion in favour of schools resuming on-campus classes subject to maintenance of safety protocols.

On January 17, the Parents Association of Mumbai wrote to chief minister Uddhav Thackeray demanding “urgent opening of schools with realistic SOPs”. “Children of Maharashtra have suffered the most with schools being closed for 700 days and counting. While education should be an essential service like it is in other countries around the world, it has been most distressing for citizens to see no importance given for education and children in Mumbai and Maharashtra… Moreover, we also want to know why bars, restaurants, malls, etc are all allowed to open while schools are not? We urgently request you to consider our request and prevent us from becoming the laughing stock of the country and world where everything but schools is open,” says the association’s letter.

Clearly, governments are more sensitive to middle class demand. A week later on January 24, Maharashtra’s ruling MVA coalition government ordered all schools statewide to restart pre-primary to class XII classes. On January 22, 22 state chapters of the Private Schools and Children’s Welfare Association (PSCWA) wrote to prime minister Narendra Modi and state chief ministers to reopen schools immediately.

In its common letter to the prime minister, PSCWA cited a statement of World Bank Global Education Director Jaime Saavedra who opines “there is no justification now for keeping schools closed in view of the pandemic”. “During 2020, we were navigating in a sea of ignorance. We just didn’t know what is the best way of combating the pandemic and the immediate reaction of most countries in the world was ‘let’s close schools’. Time has passed since then and with evidence coming in from late 2020 and 2021, we have had several waves and there are several countries which have opened schools. We have been able to see if schools opening have had an impact in the transmission of virus and new data shows it doesn’t,” said Saavedra in an interview from Washington to PTI news agency. With particular reference to India, Saavedra warned “learning poverty in India is expected to increase from 55 percent to 70 percent due to learning loss and more out-of-school children”.

Certainly, policy formulators, the academy, industry and the middle class have gravely under-estimated the covert damage that the world’s most prolonged pre-primary and primary schools lockdown has inflicted on India’s children below 14 years of age. In this connection, it’s pertinent to bear in mind that even before the Covid-19 pandemic resulted in the ill-considered 82 weeks’ schools lockdown, India’s children were ill-served by the public education system.

The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) — the outcome of massive painstaking field testing of children in rural India — published by the globally-respected Pratham Education Foundation, has been regularly highlighting the abysmal learning outcomes of routinely promoted children in primary — especially government — schools. For instance, the percentage of class V children who can’t read class II texts or do simple maths has been rising year-on-year and is currently over 56 percent (ASER 2021).

Against this backdrop, the compound effect of 82 weeks schools closure because of the pandemic, is certain to be crushing. Comments a field research study titled Loss of Learning During the Pandemic (2021) of the Bengaluru-based Azim Premji University (APU, estb.2010): “Overall loss of learning — loss (regression or forgetting) of what children had learnt in the previous class as well as what they did not get an opportunity to learn in the present class — is going (sic) to lead to a cumulative loss over the years, impacting not only the academic performance of children in their school years but also their adult lives”. The study which tested 16,067 children in 1,137 government schools in 44 districts of five states of the Indian Union, found that 92 percent of children in all classes have lost at least one specific language capability (whatever the medium of instruction) while 82 percent have lost mathematical ability acquired in the previous year.

Popat-Vats: down the drain

Tragically, the worst affected by the long drawn-out education lockdown will be youngest children in pre-primary education, deprived of critically important ECCE (early childhood care and education) for 22 months. “I fear youngest children will suffer the greatest damage because of the prolonged lockdown of pre-primaries and daycare centres. Since infants can’t be expected to mask, maintain social distance and observe Covid protocols, a majority of middle-class parents have resorted to home schooling them. In this situation although children’s learning loss may be contained, their emotional development, socialisation skills and self-respect are certain to be adversely affected. Because of the too prolonged closure of schools, many years of work to impact the value of professionally provided early childhood care and education to children in their most important formative years has gone down the drain,” lamented Dr. Swati Popat Vats, founder-president of the Early Childhood Association of India and a pioneer crusader for universal formal ECCE, in an interview to EducationWorld (EW July).

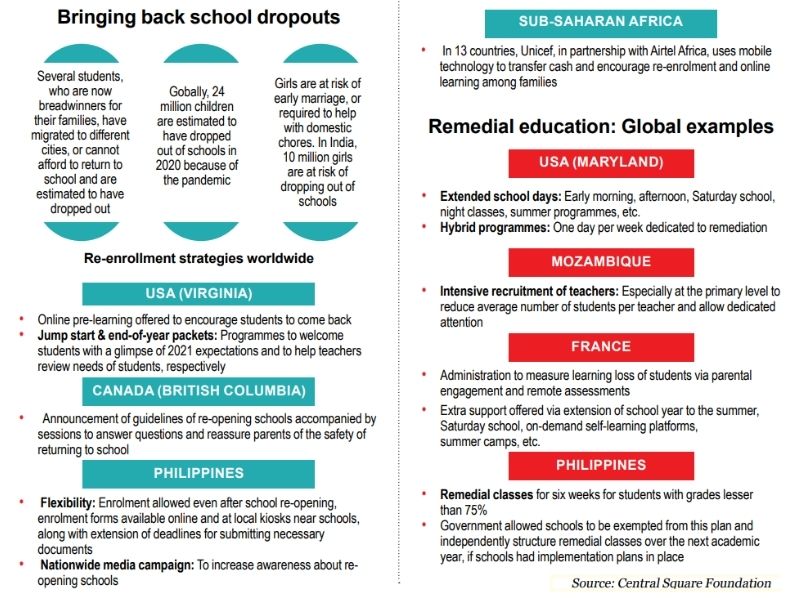

Yet even as most governments around the world are making every effort to keep schools and education institutions running, often spending billions of dollars by way of insurance cover and incentives, and are simultaneously designing and implementing remedial and learning recovery programmes, the Central government which after the first pandemic year conveniently devolved responsibility to open and shut schools on state governments, has shown no urgency in formulating a national learning recovery programme.

Rishikesh: remedial education silence

Almost two years after the pandemic and accumulating data testifying to children’s learning loss, it’s inexplicable why there are no intensive discussions at the national and state levels on remedial education programmes. The Union education ministry should have taken the lead in periodically preparing and disseminating guidelines to the states on best remedial education strategies. With most children out of school for almost two years, short-term bridge courses of three-four months won’t be sufficient. Children need at least a year-long bridge programme, if not more, to come up to age-appropriate learning levels. For instance in Karnataka, we have recommended a year-long learning recovery programme and this is different from merely truncating the syllabus. It is a complete redesign to ensure appropriate foundation is provided to children so that by end of March 2023, they are able to learn at their age-appropriate level. Simultaneously, intensive teacher development is imperative for the success of any learning recovery programme. State governments need to urgently invest resources and expertise in remedial education programmes and begin the learning recovery process,” warns Prof. B.S. Rishikesh, who heads the Hub for Education, Law & Policy at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru.

Typically, if at all, IAS and state cadre generalist bureaucrats who dominate the Union and state education ministries, are aware of the learning loss suffered by children during the pandemic, they are unlikely to be cognizant about the damage done to the mental health and well-being of children cooped up for almost two years.

Dr. Samir H. Dalwai, development behavioural pediatrician, New Horizons Child Development Centre, Mumbai, and treasurer of the Indian Academy of Pediatrics, believes the “deleterious effect” on the mental health of India’s 260 million school-age children could be greater than their learning loss. “Millions of children are showing signs of anxiety, depression, irritability, poor attention span, hyperactivity, sleep disturbances and post-traumatic stress disorder with younger children below six years showing regressive behaviours like clinging to parents, thumbsucking and bedwetting. We are facing a grave child mental health crisis,” says Dr. Dalwai, a member of Maharashtra state’s Covid-19 Pediatric Task Force.

Dalwai: child mental health crisis

Dalwai is unequivocal that state governments should no longer dilly-dally on the issue of reopening schools countrywide. “There’s sufficient scientific evidence that children infected with Covid-19 don’t fall severely ill and that schools are not Covid hotspots. For instance, in the few districts of Maharashtra where schools briefly reopened last year, there is zero Covid-19 mortality in children. In fact more children die annually in road accidents in Mumbai than due to Covid-19. Moreover with over 74 percent of the adult population double vaccinated, chances of children transmitting the virus to adults are negligible. Therefore, there is no reason to lock down schools any longer,” argues Dalwai.

In this connection, it’s also pertinent to bear in mind that world’s longest schools closure in India has not only blighted the future of the world’s largest child and youth population, it has inflicted additional damage on India’s already fragile education ecosystem.

In particular, the country’s 450,000 budget private schools (BPS) which provide affordable education to a staggering 60 million children at tuition fees ranging between Rs.6,000- 30,000 per year, have suffered huge financial loss with many forced into bankruptcy. Unpaid tuition fees have accumulated during the past two years of lockdown following reckless fee deferment directives passed by several state governments. A nationwide survey conducted last year by the Delhi-based National Independent Schools Alliance (NISA) — which has a membership of 60,000 BPS countrywide — indicates that only 38 percent of tuition fees were paid. This has severely disrupted cash flows and financial viability of BPS, and the livelihoods of an estimated 5 million teachers. Over 80 percent of private school teachers have not been paid their salaries for five months and/or have suffered pay cuts adding to the huge number of unemployed.

Be that as it may, with India having established a dubious world record of keeping schools — indeed all education institutions — under lockdown for 82 weeks while the academy, media and middle class were quiescent, children’s education loss and mental and emotional damage are water under the bridge, a fait accompli. Now it’s essential for the country’s best minds to focus on repairing the damage and saving the future of the world’s largest child and youth population.

In this connection, India Needs To Learn — A Case for Keeping Schools Open, a study released by the Boston Consulting Group and Teach For India (TFI) on the eve of India’s 73rd Republic Day, provides a route map. For a start, the report recommends adoption of a “philosophy of schools being last to close and first to open”. And to repair pandemic lockdown damage, it recommends that state governments decentralise school reopening and closures to granular level, e.g, municipal ward, gram panchayat, block levels. Second, it recommends adoption of digital technology-driven blended learning through the year i.e, continuation of online education. Third, it recommends intensive testing (e.g, weekly antigen tests), vaccination (mandatory for school staff), safety protocols (e.g, masking) and ventilation (leverage outdoor spaces, monitor ventilation) and pulling out all stops to make good the learning loss suffered by children.

Mistri: colossal repair task ahead

“The 650-plus days of severely disrupted learning, with schools nationwide closed for all children, have led to a task of colossal proportions ahead. If we are to avert a catastrophe that will permanently deprive this school-going generation of a bright future, over the next several years we will need to invest heavily to not just close the many gaps the pandemic has created but to use this as an opportunity to reimagine a new, fundamentally different education system. In this new system continuous learning is more important than board exams; children come to school to develop skills and values to live fulfilling lives and uplift the lives of others. It will take considerable mission-mode focus and resilience planning to build back better,” says Shaheen Mistri, the highly-respected founder-CEO, Teach For India (TFI). Over the past 13 years since it was promoted in 2009 TFI has recruited 3,400 well-educated graduates from the nation’s best universities and workplaces to serve for two years as teachers in under-resourced government and budget private schools.

Although academics tend to believe that a comprehensive remedial education effort is the answer, the plain truth is that except for the country’s best 3,000 schools included in the annual EducationWorld India School Rankings that are equipped with enabling infrastructure and digital connectivity, there’s little hope for children in the remaining 99 percent. Therefore, the best option is for all in K-12 education to repeat the academic year 2021-22, i.e, declare it a zero year. “The heavens won’t fall if youngest children relearn the 2021-22 syllabus to build a strong foundation for future learning. It’s certainly a better option than routinely promoting children to the next higher class where the vast majority of children will experience severe learning difficulties and stress. Extraordinary challenges require extraordinary response to bridge the huge, not yet formally calculated, almost two years’ learning loss of the pandemic era,” opines Dilip Thakore, editor of EducationWorld.

Although academics tend to believe that a comprehensive remedial education effort is the answer, the plain truth is that except for the country’s best 3,000 schools included in the annual EducationWorld India School Rankings that are equipped with enabling infrastructure and digital connectivity, there’s little hope for children in the remaining 99 percent. Therefore, the best option is for all in K-12 education to repeat the academic year 2021-22, i.e, declare it a zero year. “The heavens won’t fall if youngest children relearn the 2021-22 syllabus to build a strong foundation for future learning. It’s certainly a better option than routinely promoting children to the next higher class where the vast majority of children will experience severe learning difficulties and stress. Extraordinary challenges require extraordinary response to bridge the huge, not yet formally calculated, almost two years’ learning loss of the pandemic era,” opines Dilip Thakore, editor of EducationWorld.

In the considered opinion of your editors, the best option is for the Central and state governments to hammer out a consensus for all K-12 children to repeat the academic year 2021-22, i.e, declare it a zero academic year. This means that in the new academic year 2022-23, all schools and children will re-cover the 2021-22 syllabus and curriculums (see editorial p.10).

Admittedly this is bitter medicine for children and parents. But its outcome cannot but be beneficial for the world’s largest child and youth population.

Why schools shouldn’t lockdown

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (Unesco, estb.1945), school lockdowns impose heavy social and economic costs for entire national communities with the impact most severe for vulnerable and marginalised children. The socio-economic damage of prolonged closure of schools includes:

Interrupted learning. Schooling provides essential learning. When schools close, children are deprived of opportunities for growth and development. The disadvantages are disproportionate for underprivileged learners who tend to have fewer educational options beyond school.

Nutrition loss. Many children and youth rely on free or discounted meals provided within schools for food and healthy nutrition. When schools close, children’s growth and development is compromised.

Confusion and stress for teachers. When schools close, especially unexpectedly and for long duration, teachers become unsure of their obligations and ways and means to maintain connection with students to support learning. Transition to distance learning platforms tends to be messy and frustrating, even in best circumstances.

Parents forced to homeschool. When schools lock down, parents are asked to facilitate children’s learning at home. They are struggling to discharge this obligation. This is especially true for parents with limited education and resources.

Online learning stress. Demand for distance learning skyrockets and often overwhelms existing portals providing remote education. Moving learning from classrooms to homes at scale and in a hurry, causes great stress and challenges, human and technical.

Childcare neglect. In the absence of alternatives, working parents often leave children alone at home. This can lead to risky behaviour, including increased influence of peer pressure and substance abuse.

High economic costs. Working parents are more likely to miss work to take care of children. This results in lost wages and productivity.

Dropouts pandemic. It is a challenge to ensure children and youth return to continue their education when schools reopen. This is especially true of protracted closures and when economic shocks force children into work to boost incomes of financially distressed families.

Increased exposure to violence and exploitation. When schools lock down, child marriages increase, children are recruited into militias, sexual exploitation of girls and young women rises and teenage pregnancies become common.

Social isolation. Schools are hubs of social activity and human interaction. When schools close, children and youth are deprived of social contact, essential to learning and development.

Learning measurement challenges. Calendared assessment, notably high-stakes examinations that determine admission or advancement to higher education and institutions, are thrown into disarray. Anti-social temptation to postpone, skip or administer distance examinations raise doubts about fairness, especially when access to learning is variable. Disruption of assessment schedules imposes stress for students and their families and can prompt disengagement.

Source: Unesco

Also read: School Reopening Framework – Designed by Health-Care Experts