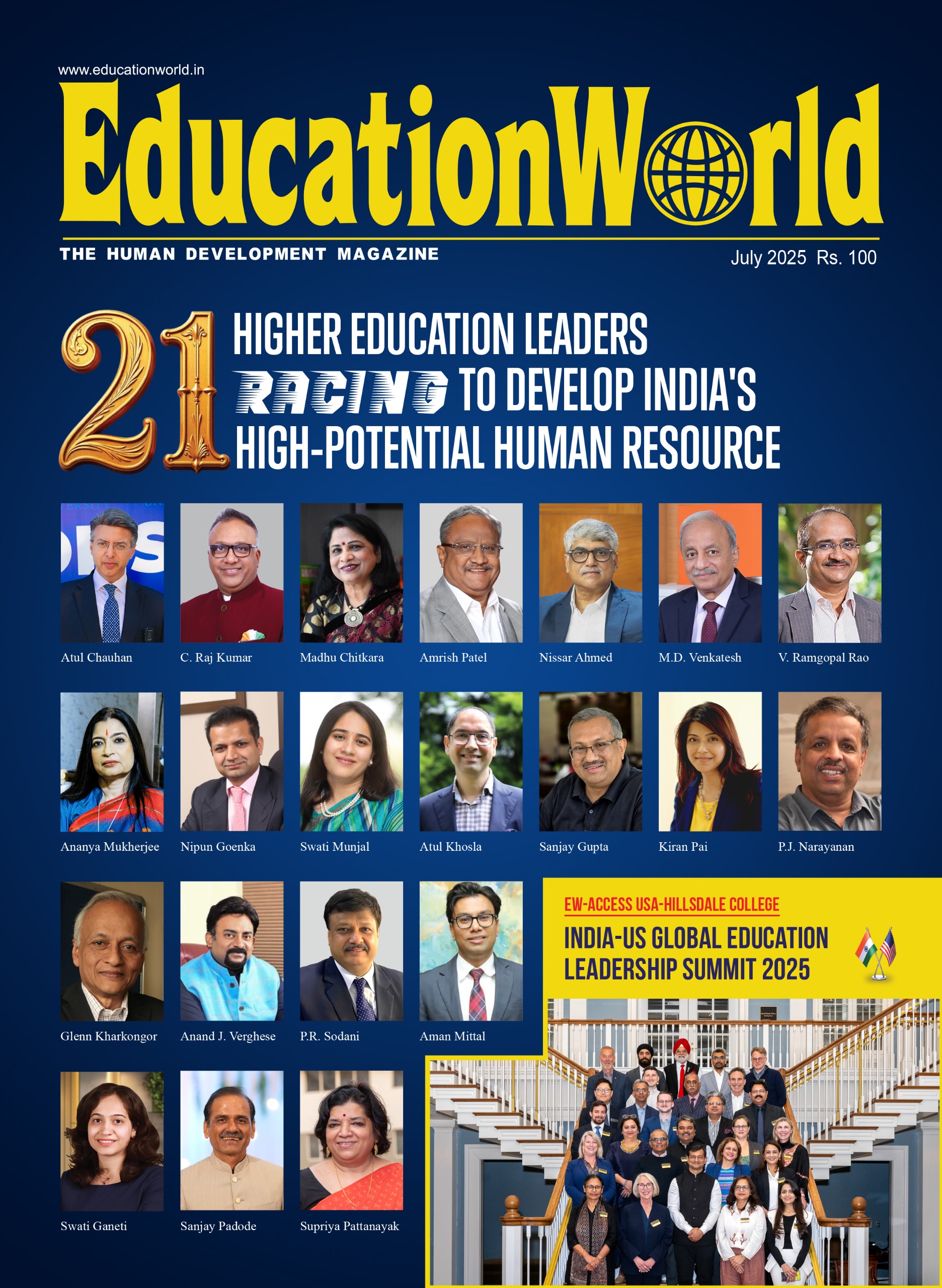

Dalit Kitchens of Marathwada

Dalit Kitchens of Marathwada

Shahu Patole, translated from the Marathi by Bhushan Korgaonkar

Harper Collins

Rs.599 Pages 354

This book endorses verity of the maxim that ‘food is the utlimate reality’. But its importance is that it reveals the connection between cuisine and the hierarchial caste system.

The recent English translation by Bhushan Korgaonkar of Marathi language writer Shahu Patole’s seminal text, Anna He Apoorna Brahma (2015) takes us into the food culture of the Mangs and Mahars of the Marathwada region of Maharashtra. It endorses verity of the maxim that ‘food is the ultimate reality’. But its importance lies in the connection it reveals between cuisine and India’s hierarchial caste system.

Patole says this is “the story of the food my parents ate and their parents ate — an acquired taste, especially one acquired through centuries of discrimination”. This rendition needed courage to write, to overcome the shame and guilt ingrained by upper caste rigidity about vegetarianism, which is further divided into sattvic, rajasic and tamasic — indicative of the social position of India’s dominant castes.

However, Patole makes it clear that the intent behind writing this book is not to oppose vegetarianism or promote non-vegetarianism but to show how beliefs, recreation and social conduct impact food habits in a regressive way. It is partly a memoir textured by social history that attempts to document social and religious hierarchy through dietary habits of two outcaste communities. The pertinent question he raises is of the fundamental right to choose what one eats. “Who has the right to decide on the cooking and eating choices, and the food culture of one’s kitchen, other than the concerned individuals or families themselves?” he asks.

Patole writes from experience of India’s food culture politics — not just dietary habits but the growing of food crops, processing and distribution of grain according to the rigid varna system.

Since sattvic or higher caste elitism is prioritised in food habits and widely propagated through food narratives, blogs, recipes, gross misconceptions about the dietary habits of marginalised Dalit communities have persisted. Do Dalits eat only various kinds of forbidden meat? Was Dalit survival based on joothan, scraps of food thrown to them by savarnas? Most importantly, did this marginalised community cook at all?

Traditional religious and social literature is silent about Dalit food and dietary habits. Therefore, this book explores, researches and documents everyday cooking and eating in Dalit households depending on affordability and availability of ingredients. Braving casteist aspersions, Patole shares actual recipes detailing specific animal parts used to prepare meals for weddings and funerals, prenatal and postnatal diets of young women, sacrifices, sacred feasts, farming and festivities. He provides details of utensils used, fuel gathered, chullas ignited, animals butchered sacrificially and dismembered part by part, in tandem with orthodox rituals and conventional practices.

This book is about the culture of marginalised lower castes and classes that trace their roots to sacred Hindu texts and religious and epic narratives — Manu, the Puranas, Mahabharata because these details have been censored from popular food discourse and media shows.

A remarkable feature of Dalit Kitchens is that the humour of rural folklore and dialect is integrated into the texture of storytelling. It is about fast vanishing rural traditions and language associated with agricultural seasons, celebration of beasts of burden that are part of farming lives, of short periods of respite for Dalit communities when landlords offered them produce grown on farms they worked. It is also about the heterogeneity of Dalit culture and cuisine, the finer nuances of practices and lore in Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Marathwada, of shared community lives.

As an insider, Patole writes of urban and modernised appropriation of kanduri and dhawara mutton preparations with eateries oblivious that these are not mere recipes but intrinsic to religious traditions. The author raises questions about ignorant consumerism that is deleting the special significance of culinary flavours like ‘kaaran meat curry’. He devotes an entire chapter to the ritual superstition of how and why a male buffalo is sacrificed in honour of Mari-aai, Lakshmi-aai or Mhasoba in the month of Ashadh and a kaaran organised to protect the village from pandemics.

Untasted but ethnic recipes of not just sacrificial meat but of a variety of seasonal vegetables are also shared by the author. Preparatory skinning and salting of animals is as meticulously described as is the plucking and seasoning of vegetables. However this is much more than a cookbook because it captures hitherto undocumented food, staples and savouries. It describes a belief and way of life, culture and language that played a role in keeping the community together — the upper castes in positions of power, the lower castes sustaining upper caste lives and the environment.

The dichotomy between persistent religious hierarchy and the practice of democracy seems incoherent to the author. Though times have changed, the reality of socio-economic deprivation is even more acute. He refers to the famine of 1972 in Maharashtra and the migration of agricultural populations to cities in search of work, that eroded food production and traditional culinary practices in rural Marathwada.

For several centuries, unpalatable references to Dalit cuisine were linked to lower caste human behaviour, unscientific belief embedded in the literature of Maratha saints (Patole refers to 52 of them and quotes from their writings). They subscribed to the varnashrama hierarchical structure to hold a community together.

Society has changed and moved on. Therefore, Patole critiques post-independence democracy in India, for retaining an outdated framework that is “not healthy for the unity and integrity of the society.” He enumerates the pitfalls of religious extremism that has intensified religion and caste-based insensitivity and intolerance that is on the rise. The urgency in this voice of dissent needs to be read and heard as it is about divisive forces that continue to disrupt the shaping of a healthy, inclusive society.

Jayati Gupta