A biography of John Lang, writer, lawyer and alcoholic who exposed British epicures who ruled India for almost 200 years, writes Mridula Garg

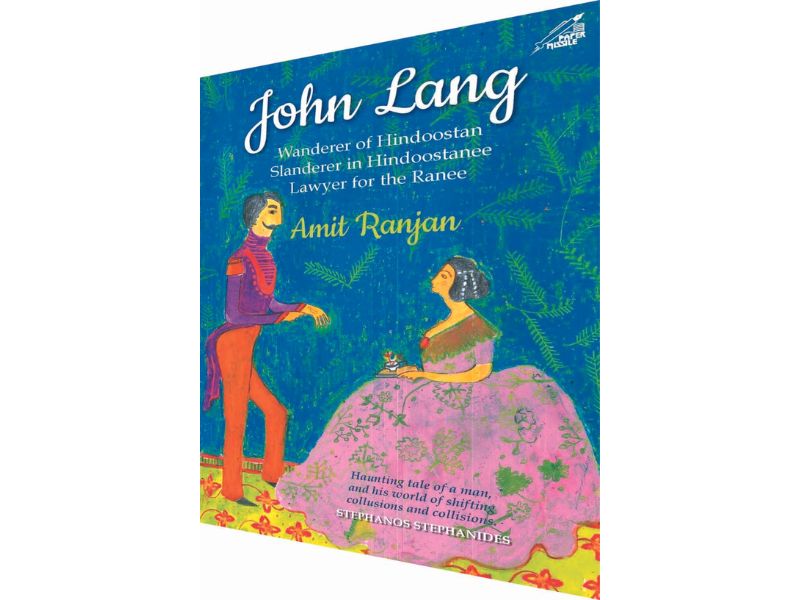

JOHN LANG: WANDERER OF HINDOOSTAN, SLANDERER IN HINDOOSTANEE, LAWYER FOR THE RANEE

Amit Ranjan

NIYOGI BOOKS

Rs.795; Pages 472

Amit Ranjan’s book John Lang poses a conundrum quite like the persona of the protagonist. Who was John Lang? Columnist, creative writer, lawyer, rebel, alcoholic or just a stupendous wit, masquerading as all of them?

Which country did John Lang belong to — Australia, England or India? Born in Australia; educated in England and resident of India, undoubtedly. But his parentage in Australia was of doubtful lineage. Was he the offspring of convicts? He was not only educated in England but had the dubious honour of being expelled by a British university. But expulsion from a self-righteous, conservative, rules-ridden university is perhaps the prerequisite of getting a real education.

One could well argue that he was one with the hoary Indian tradition of the vidushak, or glorified court jester-cum-philosopher, essential to every Sanskrit drama and reallife courts of Indian rajas and maharajas. The vidushak was given latitude to critique and ridicule the raja in every way possible. Hardly ever was he told to hold his tongue. On a rare occasion, due to jealous courtiers, he would be ordered to leave the kingdom and sometimes even incarcerated. But he would soon be pardoned and brought back to court to continue to jest with the potentate raja, which he did with not a jot of remorse. Perceptively, just how lonely it would be for a raja to be at the mercy of sycophants, day in and day out!

Unfortunately, Lang didn’t have to deal with an eccentric literature aficionado as his ruler but a faceless government, composed of banal men. So, he spent a year in jail in Vienna for an offence, the legitimacy of which is undisclosed, quite like a vidushak being jailed at a whim and acquitted soon after.

What we can’t help regret is that our gora vidushak was finally punished in the most illogical and cruel manner — he was forgotten! While Kipling, who stole from him, and Dickens, who fed off his anonymous contributions to his journal Household Words, became icons of literary history, Lang was thrown on the scrap heap!

The grand irony of Lang’s life, in keeping with the whole tenor of his mocking the establishment is that history knows him as the lawyer for the Rani of Jhansi, a case he lost, rather than as the lawyer for Lala Jotee Persaud, a case he won against all odds and with typical Langian wit. Amit Ranjan needs to be congratulated for rescuing Lang from oblivion and making him vigorously breathe again.

My favourite Lang witticism was his succinct response to a friend’s recital of Edgar Allan Poe’s celebrated 1845 poem, The Raven. All he said was, it was very good Persian — meaning thereby that it was lifted from a Persian poem — a perfect example of brevity saying a lot!

A special feature of Ranjan’s book is that he gives ample space to dates and places to lend authenticity to the narrative. One can call it a throwback to slaving over a Ph D, but more significantly it is because of his innate love of research.

Lang’s newspaper Mofussilite was founded in the 1840s, and his novels were labelled libellous by British media for depicting the dregs of society rather than the glories of British Raj over India. He was regarded as a dangerous radical, but still excited everyone’s minds. Therefore, though he poked irreverent fun at the military and civil services of British India, a lot was forgiven by his subscribers, mostly from these very services.

Ranjan writes a poem for John Lang and his friend Alice Richman. That is so Amit Ranjan, as are these lines from the poem about a man who lies in Camels Back cemetery in India:

…He could not become Dickens/ But his poetry about Jenny Dale/ And her name all around in the gale/ Tells a very old tale/ Of love.

In keeping with John Lang’s persona, Ranjan’s book though written in the English language, resonates like a work (kriti) in vernacular. By vernacular I mean a glorious play of words which explores the bhav or the nihitarth, and captures them effectively and aesthetically. To put it in English, we could say perhaps, this work captures the multi-layered hidden meanings of words.

Ranjan is kind enough to offer us quotes, showing how many of our stories told in English end with a punch line in Hindi, which is quite untranslatable in English. For example, a writer in America pointed out how a story told to her ended with the Hindi punch line — Gayi bhains paani mein. She realised that in English it could mean at best, ‘everything got drowned’, certainly not a translation. The translation would be ‘Buffalo had gone into water,’ which clearly makes no sense.

But a conundrum: Is

Ranjan following in the footsteps of Lang or casting him in his own image? In fact, there’s no subterfuge or deliberation here. The whole thing occurs quite spontaneously and why not? A young man researching his Ph D is so besotted with his subject, a writer like himself, a wanderer adopting so many countries and languages that he belongs to all of them or none at all. What would be more natural than that over the years spent together, they grow more and more alike? Amit Ranjan’s painstaking yet exuberant craft in penning this book does not allow one to fit it in any narrow category — novel, biography, literary history, historical, social and political commentary.

As the title of this critique makes amply clear, what Ranjan does is to take a cluster of forgotten ruins and excavate them bit by bit, discovering new edifices and artefacts. He explores the anatomy of a tale but then feels it’s not fully done. It needs excavation, not just examination or investigation. So, he returns to the told tale again and again and each time excavates something new for the reader to freshly wonder at.

Impatient readers might sometimes find this repetitive process a bit tedious but if you are a true aashiq of both truth and fantasy, you would thank Amit Ranjan for inviting you to come excavate a site called John Lang with him.

It reminded me of my witnessing the excavation of the 4th century ruins of Aihole in Karnataka. Just as I thought there was nothing left to discover in the void created by the intensive digging, another half-destroyed temple of exclusive and primal beauty would spring out and I would remain in awe of my anubhuti.

I felt the same exhilaration while co-excavating John Lang. Hope you do too