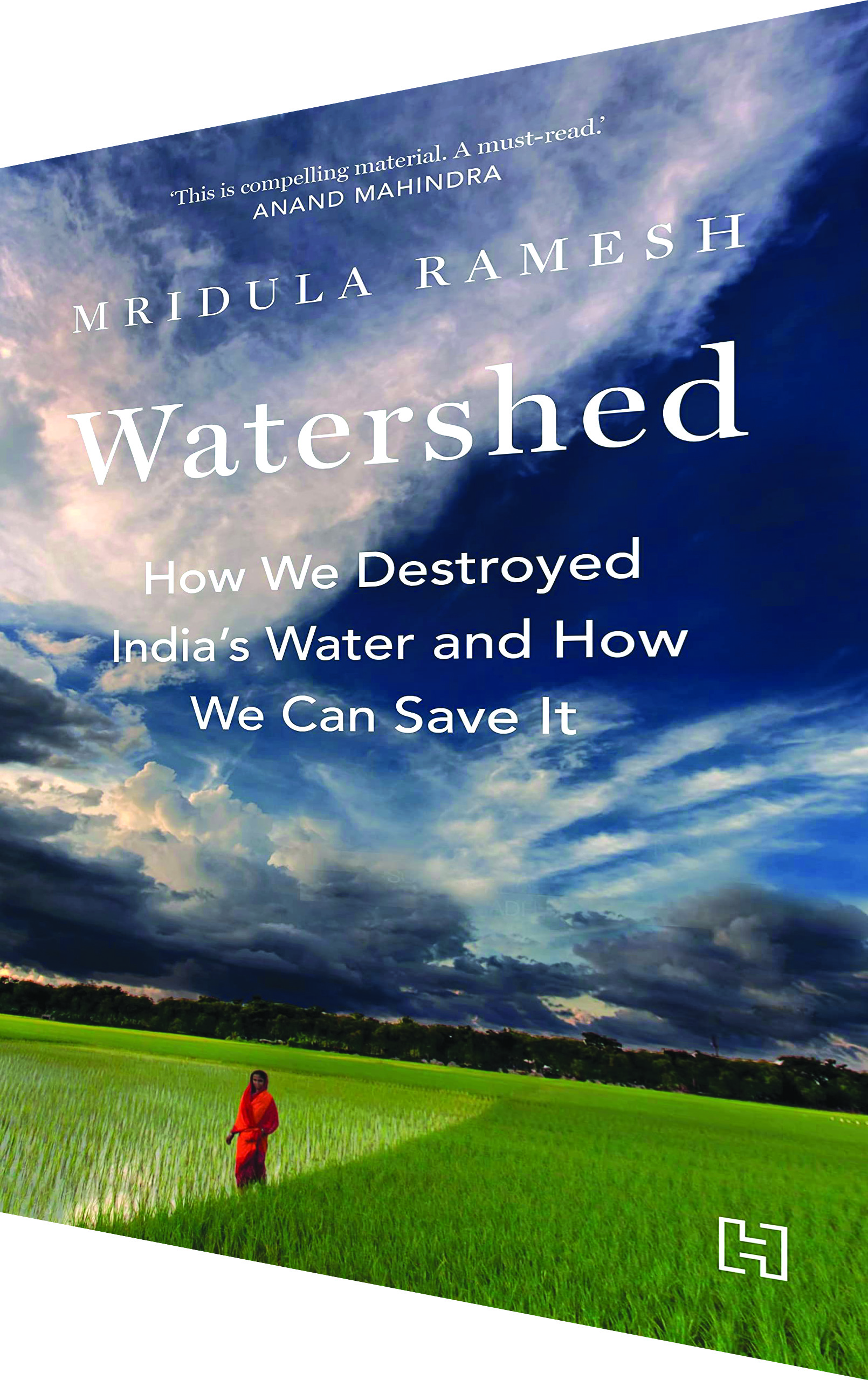

Watershed: how we destroyed india’s water & how we can save it, written by Mridula Ramesh, published by Hachette india is priced at Rs.699. A compelling narrative that traces India’s water history over 4,000 years to highlight a grave crisis confronting latter-day India, writes Mohammad Imtiyaz

Mridula Ramesh’s compelling work traces the trajectory of India’s water history over 4,000 years to highlight a grave crisis confronting the country today. Global warming is a tragic reality and it is being predicted that by 2030, India will fail to meet half its water demand. As the book’s blurb points out, water availability per person in India has been decreasing for decades, leaving parts of the country in a cruel ‘Day Zero’ situation, shuttering factories and pushing farmers over the brink. As the climate heats up, it is likely that swathes of land will be submerged, water-related extremes will reshape industry and famine will revisit the country.

Ramesh compares India’s past and present as she posits that ancient engineering and traditional technologies were designed bearing India’s volatile water availability in mind. However, their ingenuity often failed to battle monsoon variability and over-exploitation of water resources, which led to the collapse of civilisations like the Indus Valley and flooded Pataliputra, the capital of the powerful Maurya dynasty.

The book is divided in two broad sections — ‘Understanding’ and ‘Action’ — narrating how India’s relationship with water has become dysfunctional and the corrective measures required to rectify India’s burgeoning water crisis.

It begins by explaining the fault lines and stressors of India’s water resources. Emphasising the science of water and India’s monsoon uniqueness, it’s important to understand how India should manage its water given highly variable rainfall across states and regions of the country. Ramesh argues that insistence on growing commercial crops beyond a region’s water endowment, disrespecting monsoon variability and inter-annual variations of rainfall, have created India’s first water fault line.

Further, anthropocentric activities such as the decimation of forests, sand mining in rivers, depleting groundwater and rivers to gratify human needs have altered seasonality and geographical variations and resulted in a warmer world and snowmelt, creating an additional fault line in India’s water availability.

Moreover since independence, water management has been ignored at the public policy level. Ramesh cites American climate activist Bill McKibben who famously said “water doesn’t negotiate” to highlight India’s weakening of traditional and natural mechanisms that could mitigate the water crisis.

A chapter ‘Chinks in India’s Water Armour’ argues that India’s low and falling water storage capacity is the outcome of policy failures and unplanned engineering. In another chapter ‘The Green Revolution’, Ramesh attributes India’s depleting groundwater reserves to widespread use of HYV (high-yield variety) seeds, which have reduced the soil’s propensity to retain moisture. Although the Green Revolution has enabled India to become self-sufficient in foodgrains, its sustainability is doubtful, warns the author. There is a need for ingenuity to expand India’s food security as the Green Revolution formula needs copious water. Farmers growing unsuitable crops using rapidly depleting groundwater are compounding India’s water crisis, she warns.

Likewise unsuitable public policies have made the water problem acute in India’s multiplying cities. In the chapter ‘The Great Indian City Water Crisis’, Ramesh chronicles real stories to delineate the ground reality of urban India’s water crisis. She argues that water scarcity varies depending on wealth, geography, and usage.

For the wealthy, water availability is taken for granted, for the middle class, it is preferably not cognizant. The poor remain the most vulnerable in acquiring the water needed for their subsistence. Naive development plans and haphazard growth of Indian cities regardless of availability of this scarce natural resource and its overexploitation have created a ‘Day-Zero’ situation.

Ramesh explains this term as politically loaded and initially used by South African municipalities to alert people of water scarcity. Day Zero in Indian cities is an imminent and frightening reality as most urban municipalities are ill-equipped and insufficiently qualified to ensure regular supply of piped water to households. Ramesh highlights the daily predicament of the vast majority of citizens who need to jostle, cajole and bribe authorities who have the power to control this scarce resource.

In its second section ‘Action’, this book suggests scalable solutions to ameliorate India’s water crisis. According to the author, this aggravating situation demands a multi-dimensional policy approach necessitating proactive action by individuals, community, civil society, and government. First, there’s urgent need for political will to manage the water resources of India. This requires abolition of free electricity and unchecked use of groundwater to win rural votes.

Further action required includes reviving lakes, improving forest cover, rejuvenating tanks for water storage, and large-scale sewage and wastewater management solutions. Ramesh suggests media campaigns at local levels to make people aware of India’s water crisis and how climate change will aggravate its volatility and scarcity in the near future.

The uncertain income of the vulnerable Indian households makes water a scarce commodity. Therefore, there’s need to ensure minimal guaranteed incomes for economically weaker sections to make them receptive to policies that promote water management.

This book cuts across several disciplines and passes a powerful message that we are responsible for our water and we need to manage it. Rich in facts, anecdotes, ground realities, and scriptural text, it comprehensively narrates India’s water history, the present situation and future availability of this vital resource.