Gandhi implicitly understood that to attain his social reform objectives and abate Hindu-Muslim antagonism aroused by the Partition of the subcontinent on religious lines, education of the population was a necessary precondition. Therefore he expended long years in ideating and developing his prescription of basic education – Dilip Thakore

In grand-scale national celebrations orchestrated by the BJP-NDA government at the Centre which was re-elected to office in General Election 2019 of last summer, the nation is set to commemorate the sesquicentennial (150th) birth anniversary of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869-1948) for a whole year, starting October 2. Certainly, the proposed year-long nationwide celebrations to remember Mahatma (‘great soul’) Gandhi who master-minded and led India’s unprecedented freedom struggle from the cruel and exploitative rule of imperial Great Britain, are warranted.

Although with the passage of time public memory of British rule over India has dimmed, it’s useful to remember that the people of the independent Republic of India owe Mahatma Gandhi a huge debt. Right until the mid-19th century, the Indian subcontinent (as also imperial China) was the world’s richest region contributing an estimated 20 percent of global GDP. By the time the last British troops retreated in 1947 — almost two centuries after the Battle of Plassey (1757) in Bengal which marked the beginning of British Raj in India — the subcontinent had been reduced to the world’s poorest and most miserable region of the modern world.

According to most indigenous historians, the struggle for Indian independence had begun with the Indian Mutiny of 1857 (aka the First War of Indian Independence) and acquired new momentum when the Indian National Congress party was established in 1885. But it was only when Gandhi returned to India in 1914 from British-ruled South Africa (to which he had gone in his capacity as a lawyer to settle a mercantile dispute) where he conceptualised and successfully tested the doctrines of ahimsa (non-violence) and satyagraha (self-sacrifice and truth) to attain political objectives, and transformed the genteel Indian National Congress into a mass-based political party, that India’s freedom struggle began in right earnest.

In 33 years under the Mahatma’s moral and ethical leadership — he never held any official position in the Congress party — his goal of purna swaraj (complete independence) for India was attained. During his own lifetime and within the short span of three decades, almost 200 years of brutally oppressive British suzerainty over India collapsed and the mighty British Empire over which it was claimed the sun never set, unravelled soon after as colonised and subjugated people of the empire following the Indian example, demanded and wrested their independence from imperial Great Britain.

Yet as Ramachandra Guha, contemporary India’s most well-known and respected historian who has written three deeply-researched and eminently readable biographies of Mahatma Gandhi — India after Gandhi (2007, a history of post-independence India), Gandhi Before India (2013, on the evolution of the Mahatma) and Gandhi: The Years that Changed the World, 1914-48 (2018) — highlights in his latest book, Gandhi was far more than a brilliant political leader and strategist. He was also a committed social reformer determined to unite the numerous castes, communities and culturally disparate people of India into a morally strong, egalitarian and prosperous independent nation.

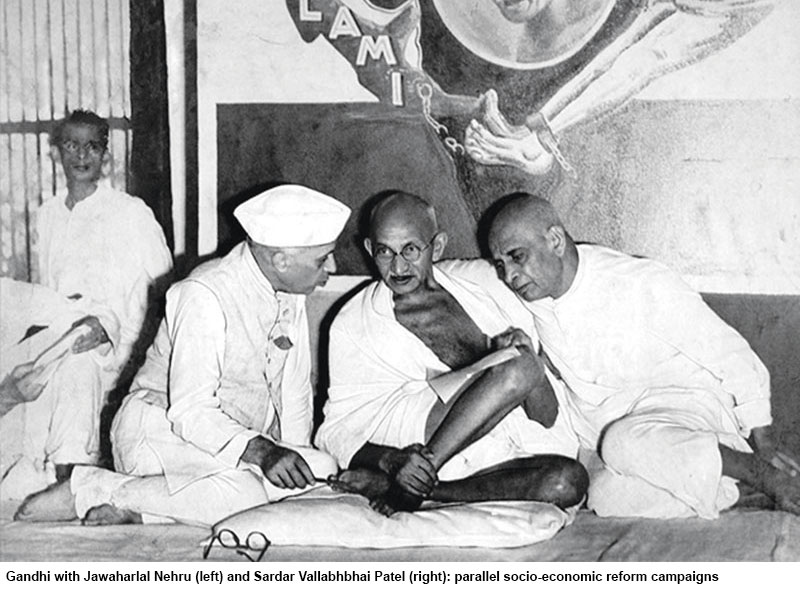

“To deliver India from British rule was by no means Gandhi’s only preoccupation. The forging of harmonious relations between India’s often disputatious religious communities was a second. The desire to end the pernicious practice of untouchability in his own Hindu faith was a third. And an impulse to develop economic self-reliance for India and moral self-reliance for Indians was fourth. These campaigns were conducted in parallel. All were of equal importance to him,” writes Guha in his 1,129-page new magnum opus Gandhi: The Years that Changed the World (see book review p.110).

Unfortunately, Gandhi was assassinated six months after the British Raj ended on August 15, 1947, but not without the spiteful departing imperialists engineering the vivisection of the subcontinent and partitioning it into the mutually antagonistic nations of India and Pakistan, divided along religious fault lines. Therefore, the Mahatma was deprived of the opportunity to impact his other equally important nation-building objectives upon independent India. Regrettably, the leaders of the Congress party and free India who followed him didn’t have the overarching vision, magnanimity and moral fibre to realise his dream of an egalitarian and prosperous independent India.

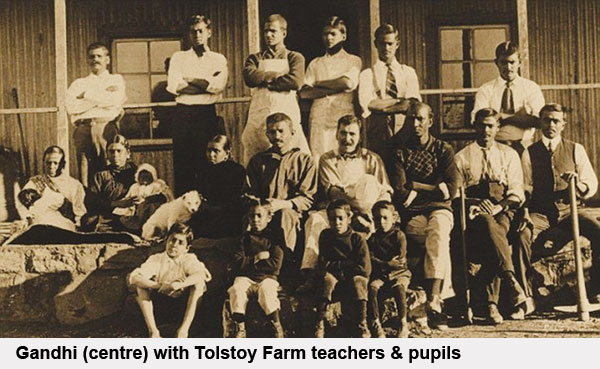

Gandhi implicitly understood that to attain his social reform objectives and abate Hindu-Muslim antagonism aroused by the Partition, education of the population was a necessary precondition. Therefore, he expended long hours in ideating and developing his prescription of an education system that would eradicate and heal caste and religious antagonisms and deep poverty which were pervasive in pre-independence India. Gandhi’s interest in schooling of children had been aroused in the early 20th century when he was in South Africa, editing a newspaper titled Indian Opinion which protested racial discrimination against the Indian population settled there. In 1910, he started a school at the Tolstoy Farm on the outskirts of Durban, gifted to him by Hermann Kallenbach, a successful architect. An informal school, it was oriented towards learning through work. Children worked the farm, shared sanitation work and learnt carpentry and sandal-making, while also learning history, geography, language, science and hand-writing. It was on Tolstoy Farm that Gandhi began to formulate his ideas on education which were incorporated into his nai talim (‘basic education’) philosophy, which he articulated in an essay in The Harijan, a weekly newspaper started by him in India in 1933.

I hold that the highest development of the mind and the soul is possible under such a system of education. Every handicraft has to be taught not merely mechanically as is done today, but scientifically i.e, the child should know the why and wherefore of every process… I have myself taught sandal-making and even spinning on these lines with good results. This method does not exclude a knowledge of history and geography. But I find that this is best taught by transmitting such general information by word of mouth. One imparts ten times as much in this manner as by reading and writing. The signs of the alphabet may be taught later… Of course, the pupil learns mathematics through his handicraft. I attach the greatest importance to primary education, which according to my conception should be equal to the present matriculation less English,” wrote Gandhi in The Harijan in 1937.

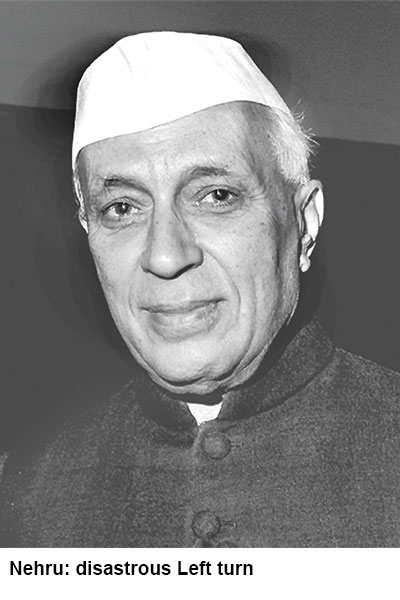

After he was assassinated by an RSS extremist in 1948, Gandhi’s ideas of education and socio-economic development fell into disuse. Independent India’s first prime minister, the Harrow and Cambridge-educated Jawaharlal Nehru, an admirer of Soviet Russia’s centrally planned heavy industry economic development model, led the newly independent nation towards a “socialist pattern of society”.

The Mahatma’s prescription of universal primary education with emphasis on developing the “head, heart and hands” of children with particular attention to their learning “handicrafts” — essentially that education should be about learning-by-doing — was dismissed as quaint and out of step with the technological temper of the times.

Especially after the death of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, the Gandhian anti-communist and socialism deputy prime minister in 1950, newly-independent India experienced the full bloom of the Nehruvian age when large dams, factories and capital-intensive public sector heavy industry enterprises became the “temples of modern India”, and engineering colleges and science universities including the IITs and IIMs were established countrywide. Public primary education to which Gandhi “attached greatest importance” suffered neglect and severe under-funding, especially in rural India.

The folly of attempting to force newly independent India, where 80 percent of the population was rural, to make a great leap forward into the industrial age following the Russian and Chinese models became evident even before Nehru’s death in 1964. At that time, it was a well-concealed secret that 20-30 million farmers, squeezed to fund the capital-intensive heavy industries Gosplans of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin and the Great Leap Forward industrialisation programme of chairman Mao, had died of starvation in these two self-proclaimed socialist countries.

But for massive American foodgrains shipped to India under the US government’s PL-480 programme, India would have suffered a similar fate. Rural and national savings canalised into giant public sector enterprises managed by government clerks, conspicuously failed to generate the surpluses budgeted to sufficiently fund primary public education and health programmes budgeted in grandiose Soviet-style five-year central plans. Panicking about the neglect of education at a time when the country’s annual GDP growth rate was stagnant at 3.5 percent even as the population was growing at 2.5 percent per year, a high-powered Kothari Commission (1964) recommended the annual expenditure for education, which had averaged 3 percent of GDP, be urgently doubled to 6 percent.

However, this main recommendation of the Kothari Commission was not implemented at the time or thereafter, down to the present day. For the past 72 years since under Gandhi’s nation-building moral leadership India attained political independence, the annual outlay (Centre plus states) for education has averaged a mere 3.5 percent. Some historians and political pundits blame Nehru for disparaging Mahatma Gandhi’s framework for human capital development as obsolete. Charged with fervour for building giant public sector enterprises (PSEs) mandated to dominate the “commanding heights of the Indian economy”, the Nehru government poured national savings into PSEs managed by business-illiterate bureaucrats and over-promoted clerks who utterly failed to generate the budgeted surpluses for investment into human capital development, i.e, education and health.

Neglect of education, especially at the primary and secondary levels during the Nehruvian era sealed India’s fate as a prosperous emerging nation and a genuine enlightened democracy. Among the first things that countries like Japan, South Korea and Singapore did to become prosperous was to focus on education — both mass and higher education. Nehru knew only one formula for development: socialism and public sector — which took India to dogs,” (sic), writes Rajnikant Puranik, an alumnus of IIT-Kharagpur and IIT-Kanpur, former banker and IT professional in a history titled Nehru’s 97 Major Blunders (Pustak Mahal, 2016).

Neglect of education, especially at the primary and secondary levels during the Nehruvian era sealed India’s fate as a prosperous emerging nation and a genuine enlightened democracy. Among the first things that countries like Japan, South Korea and Singapore did to become prosperous was to focus on education — both mass and higher education. Nehru knew only one formula for development: socialism and public sector — which took India to dogs,” (sic), writes Rajnikant Puranik, an alumnus of IIT-Kharagpur and IIT-Kanpur, former banker and IT professional in a history titled Nehru’s 97 Major Blunders (Pustak Mahal, 2016).

In 1964, Lal Bahadur Shastri succeeded Nehru as prime minister and showed signs of course correction and focusing national attention on developing and nurturing the country’s vast but neglected human capital. However, he died under mysterious circumstances in Tashkent (Soviet Union) in 1966 after winning a short but full-fledged war against Pakistan.

Shastri was succeeded by Nehru’s daughter Indira Gandhi whose faith in PSEs was greater than her father’s. In 1969, she nationalised the country’s 14 major private banks and shortly thereafter the coal and mining industries. With PSEs unable to generate the surpluses required to fund social sector expansion and development, annual outlays for education plunged below 3 percent of GDP. In particular, public primary education to which Gandhiji attached the “highest importance” dropped to the bottom of the national development agenda.

Shastri was succeeded by Nehru’s daughter Indira Gandhi whose faith in PSEs was greater than her father’s. In 1969, she nationalised the country’s 14 major private banks and shortly thereafter the coal and mining industries. With PSEs unable to generate the surpluses required to fund social sector expansion and development, annual outlays for education plunged below 3 percent of GDP. In particular, public primary education to which Gandhiji attached the “highest importance” dropped to the bottom of the national development agenda.

After the belated liberalisation and deregulation of the dirigiste socialist economy in 1991, education has moved higher up the national agenda. But that’s mainly because of a surge of new initiatives including international benchmarking in the private education sector, while the country’s 1.20 million government schools remain stranded in shallows and misery. According to the latest Annual Status of Education Report 2018, over 50 percent of class V children in government schools of rural India cannot adequately read and comprehend class II textbooks in their vernacular languages, and a mere 39 percent of class VIII pupils can do simple division and multiplication sums.

As a result, despite providing free mid-day meals, uniforms and free-of-charge tuition, government schools across the country are emptying out with children from even poorest bottom-of-pyramid households being enrolled in low-cost budget private schools (BPS) — a unique Indian (and third world) phenomenon. According to the Centre for Civil Society (CCS), a highly respected Delhi-based think tank, the number of BPS countrywide is over 400,000 with an aggregate enrolment of a staggering 60 million children, a telling measure of the disillusionment of bottom-of-pyramid households with free-of-charge government schools.

Yet instead of improving teaching-learning standards in the country’s 1.20 million government primary-secondary schools and disciplining public school teachers — 25 percent of the country’s 7.5 million government school teachers are absent every day — in 2009, the Congress-led UPA-II government at the Centre legislated the Right of Children to Free & Compulsory Education (aka RTE) Act, which obliges private schools to reserve 25 percent of capacity in elementary (classes I-VIII) school for children from poor households in their neighbourhood at way below-cost tuition fees. Moreover s.19 of the RTE Act especially targets affordable BPS by mandating stringent capital-intensive infrastructure norms (government schools are exempt) with clear intent to force their closure, a typical dog-in-manger stratagem of socialist India’s all powerful neta-babu brotherhood. However, under the banner of the NISA (National Independent Schools Alliance) supported by CCS (and EducationWorld), a large number of BPS countrywide have succeeded in obtaining stay orders against s.19 compliance and forced closure notices.

Apart from targeting BPS, the country’s control-and-command neta-babu brotherhood is also harassing the country’s 320,000 independent private schools which host over 40 percent of the country’s 250 million in-school children. Over the past two years, to pander to the electorally influential middle class which shuns government schools like the plague, almost all state governments have enacted legislation to control and/or cap tuition fees of private (financially) independent schools. The logic that it can’t get first world education at third world prices seems to be beyond the cognitive capabilities of India’s pampered subsidies-addicted middle class.

Apart from targeting BPS, the country’s control-and-command neta-babu brotherhood is also harassing the country’s 320,000 independent private schools which host over 40 percent of the country’s 250 million in-school children. Over the past two years, to pander to the electorally influential middle class which shuns government schools like the plague, almost all state governments have enacted legislation to control and/or cap tuition fees of private (financially) independent schools. The logic that it can’t get first world education at third world prices seems to be beyond the cognitive capabilities of India’s pampered subsidies-addicted middle class.

Ironically, the western seaboard state of Gujarat reputed for its free enterprise culture — and prime minister Narendra Modi’s bailiwick — has introduced the most draconian legislation to cap private school tuition fees. Quite clearly, the intent of the educracy is to level down private schools to government school standards rather than vice versa.

The severe damage that post-independence India’s education bureaucracy, their brains addled with simpleton amir-garib socialism, have inflicted on Indian education and human capital development is not restricted to K-12 education. None of India’s 900 universities, some of them of over 150 years vintage, is ranked in the recently published authoritative Times Higher Education’s league table of the world’s Top 200 universities. Conversely, the neighbouring People’s Republic of China has seven universities ranked in the THE 200. India’s highest ranked higher education institution is IISc, Bangalore, ranked #301-350.

The socio-economic consequences of poor quality tertiary education dispensed by the vast majority of Indian universities have been devastating. According to a 2018 study of Aspiring Minds, a Delhi-based recruitment and employees testing firm, 75 percent of graduates of India’s engineering colleges and universities are unsuitable for employment in Indian and foreign multinational companies. Moreover, 85 percent of graduates of the country’s arts, science and commerce colleges are unemployable. This damning indictment of the country’s education system suggests that the vast majority of the population is unemployable. It also explains why government, agriculture and industry productivity in India is among the lowest worldwide.

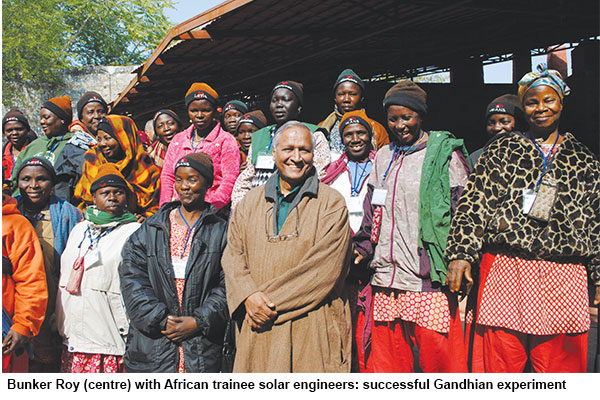

One of the few, if not sole, education institutions which has successfully implemented the education philosophy and prescription of Mahatma Gandhi is the low-profile Barefoot College, Tilonia (BC, estb.1972), a small green village (pop. 4,000) in the western border state of Rajasthan (pop. 68 million). BC was promoted over four decades ago by Sanjit (‘Bunker’) Roy, an alum of the top-ranked Doon School, Dehradun and the blue-chip St. Stephen’s College, Delhi, his wife Aruna, an IAS officer, and three professors of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, after Roy experienced an epiphany while interacting with a group of illiterate but knowledgeable villagers in water-scarce Rajasthan four decades ago.

Today, 46 years after commencing hesitant operations, BC is not only a model rural community college engaged in transforming illiterate villagers of both sexes into solar energy and rainwater harvesting engineers and educators, it’s also the rural development hub of 200 villages in the Ajmer and Jaipur districts of Rajasthan, with substantially higher human development indices and living standards than the country’s much neglected stone-age hamlets.

“BC is the only college worldwide which consciously follows the teaching, life and work style of Mahatma Gandhi, who envisioned an India comprising thousands of self-sustaining village republics. Here we don’t accept that village farmers, artisans and service providers are uneducated even if they are illiterate. On the contrary, we believe most village folk are well- educated having inherited traditions of crafts, water management, weather forecasting and agriculture knowhow and survival which are thousands of years old. In BC, our objective has been to revisit education by reviving the native skills of village India to tangibly improve people’s lives by enabling them to generate solar energy, manage water resources and build capacity for sustained development,” Roy informed your correspondent, who visited Barefoot College, Tilonia in 2012 to briefly experience the transformative Gandhian socio-economic experiment of this extraordinary teaching-learning institution — the “only college built by the poor, for the poor and for the past 40 years managed, controlled and owned by the poor”.

Unfortunately, repeated efforts of your correspondent to arouse Roy for an update on the progress and outreach of BC for this Mahatma Gandhi sesquicentennial feature, received no response. Unlike Gandhi who had excellent public and media relations skills, Roy is deficient in this life skill. “I am a poor public speaker. I hate crowds,” he told me when I last interviewed him in 2016. However, this modesty while becoming, has prevented Roy and BC from sufficiently influencing national education policies to the detriment of the public interest.

Be that as it may, Roy is firm in his belief that neglect of Gandhi’s advice to Nehru and the first government to accord highest priority to public primary education was an egregious error. “We need demystified and decentralised solutions that are bottom-up rather than top-down. We need to provide productive employment in village India so the rural poor are not forced to migrate to cities. We need to study Gandhi and revive the public primary education system which is in a shambles. Because of weak education foundations, the entire Indian economy is crumbling,” Roy told EducationWorld three years ago (see https://www.educationworld.in/we-need-to-revive-public-primary-education/).

Regrettably, seven decades after Gandhi was assassinated before he could exert any influence on the first government of independent India, his recommendations for universalisation of primary education and advice to prioritise agriculture and rural development — the essence of Gandhi’s national development prescription — have been lost in translation and mired in confusion.

Today, the popular perception of the Mahatma is that of a great soul who preached spiritually uplifting nostrums such as civic and personal hygiene, eradication of caste discrimination and promotion of inter-religious harmony. The reality that Gandhi had a deep understanding and insights into the development priorities of the masses — which explains why he was successful in transforming the elitist Indian National Congress debating society into the mass-based Congress party — has been obfuscated by design or neglect.

An erudite intellectual who had explored every nook and corner of the country, Gandhi knew the priorities of the newly-liberated masses of India were village development, cooperation between castes and communities, enlightened capitalism and universal basic education. But unfortunately for citizens of the world’s most populous democracy, these core principles of Gandhi’s national development philosophy were substituted by his obiter dicta on civic cleanliness, hygiene and morality and ethics.

“More than any of his contemporaries, Gandhiji understood that basic primary education in its broadest sense was the most important priority for developing India into a strong and harmonious nation. Gandhiji believed that although it was important for children to learn the 3 R’s, it wasn’t sufficient. Therefore, he took pains to research and expound his nai talim or basic education pedagogy. He believed that body, mind and spirit — head, heart and hand — of youngest children need to be educated simultaneously. That’s why he accorded great importance to all children learning handicrafts. But his concept of learning crafts was beyond vocational education. He believed children should also be taught the where, how and why of production so they respect the philosophy and processes of production and transform into life long learners. He believed that if children learn core academic subjects along with learning about the world of work, the ills of casteism and religious intolerance would automatically disappear from society. Unfortunately, there’s little trace of his nai talim philosophy in the education system or even in the National Education Policy 2019 draft,” says Pradip Dasgupta, former professor of physics at the Siddharth College, Mumbai (1978-2013) and currently secretary of the Nai Talim Society, Sevagram, Wardha, a learning community (ashram) established by Gandhi in 1942.

“More than any of his contemporaries, Gandhiji understood that basic primary education in its broadest sense was the most important priority for developing India into a strong and harmonious nation. Gandhiji believed that although it was important for children to learn the 3 R’s, it wasn’t sufficient. Therefore, he took pains to research and expound his nai talim or basic education pedagogy. He believed that body, mind and spirit — head, heart and hand — of youngest children need to be educated simultaneously. That’s why he accorded great importance to all children learning handicrafts. But his concept of learning crafts was beyond vocational education. He believed children should also be taught the where, how and why of production so they respect the philosophy and processes of production and transform into life long learners. He believed that if children learn core academic subjects along with learning about the world of work, the ills of casteism and religious intolerance would automatically disappear from society. Unfortunately, there’s little trace of his nai talim philosophy in the education system or even in the National Education Policy 2019 draft,” says Pradip Dasgupta, former professor of physics at the Siddharth College, Mumbai (1978-2013) and currently secretary of the Nai Talim Society, Sevagram, Wardha, a learning community (ashram) established by Gandhi in 1942.

Ironically, some core tenets of Gandhiji’s nai talim philosophy of educating the heads, hearts and hands of children are more respected and practised in the country’s much reviled private independent schools rather than in government institutions in which learning beyond the 3 R’s tends to be the exception. For instance, Kiran Bir Sethi, founder-director of Ahmedabad’s top-ranked Cambridge International (UK)-affiliated Riverside School (estb.2001), sited on the banks of the River Sabarmati “diagonally opposite Gandhiji’s Sabarmati Ashram”, says that core elements of the Mahatma’s Nai Talim prescription have shaped Riverside’s unprecedented, global Design for Change (DFC) co-curricular education programme which is being practised by 2 million children in 60,000 schools and 67 countries around the world.

“Riverside’s DFC programme is based on Gandhiji’s precept that individuals should implement the change they want to see. The DFC programme inculcates this advice in children aged 8-15 in primary-secondary education, encouraging them to initiate community service projects in their neighbourhoods using their heads, hearts and hands, i.e, their imagination, empathy for the community, and labour. The objective of DFC, which has inspired schools around the world, is to teach children from youngest age to become proactive agents of change — to learn to solve social problems cheerfully with empathy and compassion. This was Gandhiji’s example. The spirit of the Mahatma is alive in Riverside School,” says Sethi, currently in the Vatican City, Italy to discuss with Pope Francis ways and means to reach the DFC programme to a greater number of countries.

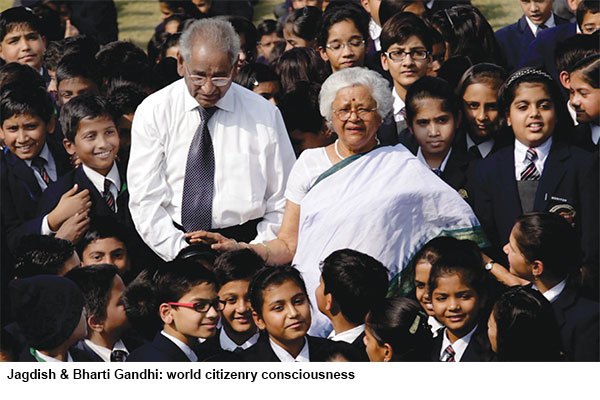

Another highly reputed co-ed day school which has been substantially influenced by the heads, hearts and hands education philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi is the City Montessori School, Lucknow (CMS, estb.1950), certified by Guinness World Records as the world’s largest single city school (57,000 students in 14 campuses) and ranked the #1 co-ed day school in Uttar Pradesh (pop. 215 million) in the EW India School Rankings 2019-20. Dr. Jagdish and Dr. Bharti Gandhi, who co-promoted this co-ed school almost seven decades ago, adopted jai jagat (victory to the world) based on the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi as its motto.

“We took to heart Gandhiji’s observation that ‘if we want real peace in the world, and to wage a real war against war, we shall have to begin with the children’. Since then we have worked for six decades to develop students’ consciousness as world citizens in the spirit of vasudhaiva-kutumbam (the world is one family). We promote students’ and teachers’ engagement with world affairs through olympiads, international student events related to promotion of world peace which are attended by 9,000 children from across India and abroad every year. These events introduce children to the importance of contemporary issues such as law, order and justice; global governance architecture for peace; care of the environment; communal harmony, interfaith dialogue and gender equality. CMS is the only school in the world to have received the UNESCO Prize for Peace Education,” says Dr. Jagdish Gandhi, promoter-chairman of CMS.

Although in the great majority of India’s top-ranked schools with glittering infrastructure, the Nehruvian rather than Gandhian philosophy of education is dominant, the influence, if not spirit, of Mahatma Gandhi is alive in a large number of low-profile schools across the country. For instance, the educational ideals of Gandhi pervade the low-profile M.P. Shah English High School, Vile Parle, Mumbai (MPSEHS, estb.1954).

In 1929, Gandhiji donated a sum of Rs.25,000 collected by him from well-wishers to the Bagini Seva Mandir Kumarika Mandal (BSMKM) — a trust to keep elderly women engaged in productive work. The trustees of this all-women organisation started a nursery school whose foundation was laid by Gandhiji himself that very year. This nursery gradually expanded into the full-fledged K-10 MPSEHS registered in 1954. Currently, this co-ed school affiliated with the Maharashtra SSC examinations board has 1,100 students mentored by 90 teachers on its muster rolls.

Nailesh Dalal, a successful Mumbai-based stockbroker who graduated from MPSEHS in the mid-1970s, and wife Smruti (also an MPSEHS alumna and trustee of the BSMKM all-women’s trust) recall that it was the first school in Mumbai to be managed entirely by women in accordance with Gandhi’s directive to educate girl children and women. “Unusual for that era, Gandhiji strongly advocated equal education for girl children because he understood that an educated woman will ensure the education of her entire family. We wore khadi uniforms and raised funds for project assignments to better the local community through learning to work with our heads, hearts and hands, and went door-to-door offering to do household chores to raise money for our projects if necessary. This taught us the purpose of work and dignity of labour. Tuition fees in MPSEHS were very low — Rs.5 per month for class V children, Rs.6 for class VI and so on. We received an excellent blend of academic and work education defined by simple living, respect for fellow students and the work-related advantages of tolerance and brotherhood. I believe that we were among the first students in India to be encouraged to think globally and work locally,” says Dalal, a commerce graduate of Bombay University with an MBA from the top-ranked S.P Jain Institute of Management & Research, Mumbai and promoter-director of Dalal & Broacha, Mumbai, a highly respected stockbroking firm.

As the year-long celebrations of Mahatma Gandhi’s sesquicentennial get underway, it’s important to remember that his nation-building prescription extended beyond education, and accorded top priority to rural development and employment, and the wage goods, rather than the heavy industry development model. Gandhi also prescribed high priority to eradication of caste discrimination and promotion of inter-religious harmony because of his subliminal awareness that social peace and cohesion is the precondition of economic progress.

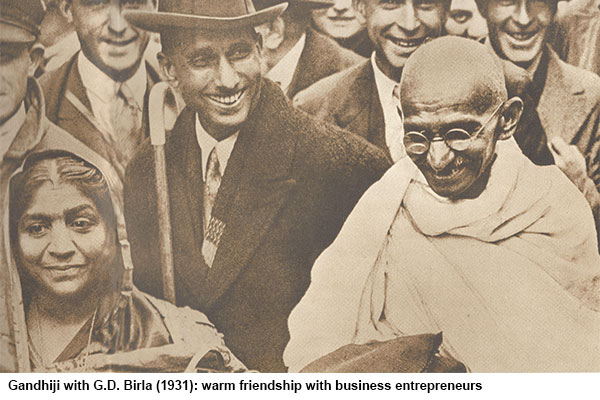

Moreover, it’s pertinent to note that Gandhi never entertained any hostility towards private enterprise, business and industry which became the hallmark of Nehruvian socialist India. On the contrary, Gandhiji admired and established close friendships with brilliant business entrepreneurs such as G.D. Birla, Ambalal Sarabhai, Walchand Hirachand, J.N. Tata who had succeeded in developing large industries and businesses despite the numerous hurdles strewn in their path by jealous British Raj administrators.

Indeed it is no exaggeration to state that Indian businessmen of that era, especially the late G.D. Birla (1894-1983) funded India’s freedom movement. Well aware that the subcontinent has a centuries old tradition of free enterprise, Gandhiji had no time or patience with communist and socialist ideology which predicates an omnipresent and omniscient State regulating all economic activity.

On the contrary, he believed that the economic development programme of Indian socialists “ignored Indian conditions”. “The socialists’ manifesto called for ‘the progressive nationalisation of all the instruments of production, distribution and exchange’. Gandhi thought this ‘too sweeping’… Almost all of them have westernised minds. None of them knows the real conditions in Indian villages, or perhaps even cares to know,” Ramachandra Guha quotes Gandhi as saying in his thoroughly researched magnum opus Gandhi: The Years that Changed the World.

However, despite his dislike for Nehru’s ingenuous socialism whose logical end the latter believed was communism, in 1946 Gandhi made an egregious error of judgement in backing Nehru for the post of Congress party president even though he was well aware that the party president of that year would automatically become free India’s first prime minister. Under the party’s constitution, the Congress president was to be elected by the 19 heads of the Provincial Congress Committees. Although Sardar Patel polled 15 votes against Nehru’s nil (four abstentions), when Nehru threw a temper tantrum, Gandhi requested Patel — his most faithful lieutenant — to stand down. It was a fateful decision for which the country has paid — and continues to pay — a heavy price.

Unsurprisingly, after the Mahatma’s assassination in 1948 and Sardar Patel’s death two years later, the Congress party and the country under Nehru’s undisputed leadership, took a sharp Left turn. Leaders of Indian industry such as G.D. Birla, J.R.D. Tata, Walchand Hirachand, Lala Shri Ram, Ambalal Sarabhai, and Kasturbhai Lalbhai among others, who were poised to impact India Inc upon the world, were cast into the outer darkness and became pariah importunists in the corridors of power of socialist India. As founding-editor of Business India and Businessworld — India’s pioneer business magazines — your correspondent was the sole journalist to interview and write major features on J.R.D. Tata and G.D. Birla and recorded that they died bitter, disillusioned individuals because of the ingratitude and public vilification they experienced in socialist India.

As the nation begins to celebrate the 150th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi, it’s important for educators and teachers in particular, to ensure that Gandhiji’s core principles and messages — eradication of casteism and abhorrence of the practice of untouchability; Hindu-Muslim harmony (for which he sacrificed his life) and economic and moral self-reliance for all Indians — are integrated into school curriculums. Floundering in a sea of illiteracy, encumbered with a failed education system and experiencing a resurgence of caste animosities and religious disharmony even as economic growth is tanking within an increasingly inegalitarian society, the nation needs to revisit the ideals and message of Mahatma Gandhi.

Celebration of the sesquicentennial birth anniversary of the greatest social reformer that walked upon the soil of India, offers the people of this high-potential nation an opportunity to unite, heal and rejuvenate. That would be the greatest tribute to the memory of the Father of the Nation.

Also read:

Remembering Gandhi on his 150th birthday