EARLIER THIS YEAR WE LOST INDIA’S stalwart campaigner for sane policies that affect little children’s education. If Mina Swaminathan were around and active, I wouldn’t have ventured to critique the recently presented (October 20) National Curriculum Framework for Foundational Stage (NCFFS) 2022.

NCFFS aims to integrate anganwadis with early primary classes. The stated purpose of this restructuring is to focus on foundational literacy. It marks a remarkable act of walking backwards. This is not, of course, the first time the system is doing so. Our systemic history is full of examples that an English teacher might use to explain usage of ‘one step forward, two steps backwards’.

We know now that the new NCF will be a huge document, divided stage-wise. What has just been published has 354 pages and it covers only the ‘foundation stage’ — early childhood and primary school years. As the policy document clarifies, the government wants anganwadis to be officially tied to early primary classes.

If this happens, it will constitute a major structural change. Anganwadis were the institutional expression of the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) programme introduced in 1975. The programme envisioned feeding millions of India’s infants deprived of basic nutrition and care. Their psychological development at this early stage of life was to be addressed by a routine offering play and movement, colour and music. These were ambitious goals, and they have remained elusive in most states of the Indian Union.

But even a limited ICDS must be recognised as a milestone. It was the great achievement of women scholars including Mina Swaminathan who pushed the State to acknowledge its duty towards children of the poor. Anganwadis are run by women. In the northern states, they are poorly paid and their struggle to be treated with dignity hasn’t made much headway. Now, if anganwadis are attached to primary schools, one can hardly imagine things getting better for infants and their care-givers, especially when the new focus will be on literacy. The pipedream of informal child-centred education in India’s villages and urban slums can be expected to recede further.

A document that doesn’t acknowledge state-level realities and variation in efforts to negotiate financial limitations, cannot be expected to serve as a guide to action. But even as an academic document, the sweep and verbosity of NCFFS are amazing. It contains just about everything that has ever been said or discussed in the context of child development, language learning and acquisition of literacy. In places it reads like a voluminous assembly of dissertations. Ancient Indian philosophy also finds a place. How it will help the primary education system to deal with harsh realities that have been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, is difficult to imagine.

Prima facie, its emphasis on the acquisition of dependable literacy at an early stage seems a good idea. If we look back, the ghost of literacy has always haunted the establishment. For decades progressive educators have argued that literacy cannot be isolated from intellectual and aesthetic nourishment during childhood. Numerous studies have demonstrated that India’s kindergartens and primary schools are so obsessed with literacy that they underplay everything else. And within literacy, our institutions put mechanics above meaning. These are not just stumbling blocks: they are characteristic weaknesses of the system.

Adownside of the stage-wise approach to curriculum planning is that it allows us to view interaction between stages. The case of primary and upper primary education is typical. The hard-won shift towards the ‘elementary’ stage promised a change, but the new education policy document and NCFFS indicate that the movement towards elementary education is unlikely to be supported. Other stages of education are similarly perceived in a fragmented way. If each stage of school education is going to be covered in the style of this document, we can expect over one thousand pages of unhelpful prolixity.

A curriculum framework is supposed to be an enabling document. If it is to be useful, the intended readership must be taken into account. If teachers are part of that readership, their daily struggles and achievements under highly diverse conditions should find reflection. Alas, teachers are far too remote from the concerns of people who prepare policy documents. Our system considers prescribed textbooks as a sufficient resource for the teacher.

Moreover we hear that teachers will be monitored by technology. Their autonomy is of zero value to the authorities and school managers, fond of uniformity. They believe that uniformity is the key to quality. Such belief offers little scope for confidence in the teacher. Every effort is made to keep teachers under a tight grip every hour of the day. A teacher who is so regimented can hardly nourish an autonomous mind in the child, no matter what the subject.

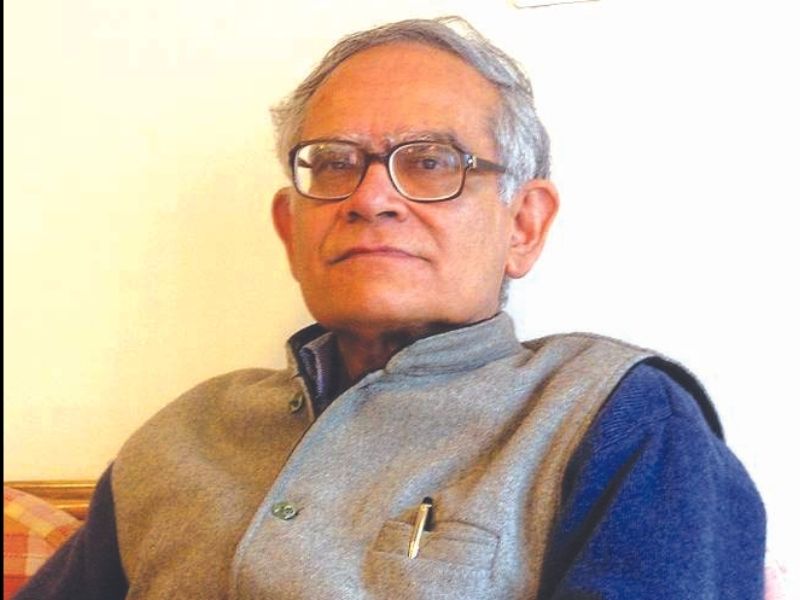

(Dr. Krishna Kumar is a former director of NCERT and NCTE and author of Smaller Citizens (2021))

NCFFS 2022: Ghost of early literacy

EARLIER THIS YEAR WE LOST INDIA’S stalwart campaigner for sane policies that affect little children’s education. If Mina Swaminathan were around and active, I wouldn’t have ventured to critique the recently presented (October 20) National Curriculum Framework for Foundational Stage (NCFFS) 2022.

NCFFS aims to integrate anganwadis with early primary classes. The stated purpose of this restructuring is to focus on foundational literacy. It marks a remarkable act of walking backwards. This is not, of course, the first time the system is doing so. Our systemic history is full of examples that an English teacher might use to explain usage of ‘one step forward, two steps backwards’.

We know now that the new NCF will be a huge document, divided stage-wise. What has just been published has 354 pages and it covers only the ‘foundation stage’ — early childhood and primary school years. As the policy document clarifies, the government wants anganwadis to be officially tied to early primary classes.

If this happens, it will constitute a major structural change. Anganwadis were the institutional expression of the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) programme introduced in 1975. The programme envisioned feeding millions of India’s infants deprived of basic nutrition and care. Their psychological development at this early stage of life was to be addressed by a routine offering play and movement, colour and music. These were ambitious goals, and they have remained elusive in most states of the Indian Union.

But even a limited ICDS must be recognised as a milestone. It was the great achievement of women scholars including Mina Swaminathan who pushed the State to acknowledge its duty towards children of the poor. Anganwadis are run by women. In the northern states, they are poorly paid and their struggle to be treated with dignity hasn’t made much headway. Now, if anganwadis are attached to primary schools, one can hardly imagine things getting better for infants and their care-givers, especially when the new focus will be on literacy. The pipedream of informal child-centred education in India’s villages and urban slums can be expected to recede further.

A document that doesn’t acknowledge state-level realities and variation in efforts to negotiate financial limitations, cannot be expected to serve as a guide to action. But even as an academic document, the sweep and verbosity of NCFFS are amazing. It contains just about everything that has ever been said or discussed in the context of child development, language learning and acquisition of literacy. In places it reads like a voluminous assembly of dissertations. Ancient Indian philosophy also finds a place. How it will help the primary education system to deal with harsh realities that have been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, is difficult to imagine.

Prima facie, its emphasis on the acquisition of dependable literacy at an early stage seems a good idea. If we look back, the ghost of literacy has always haunted the establishment. For decades progressive educators have argued that literacy cannot be isolated from intellectual and aesthetic nourishment during childhood. Numerous studies have demonstrated that India’s kindergartens and primary schools are so obsessed with literacy that they underplay everything else. And within literacy, our institutions put mechanics above meaning. These are not just stumbling blocks: they are characteristic weaknesses of the system.

Adownside of the stage-wise approach to curriculum planning is that it allows us to view interaction between stages. The case of primary and upper primary education is typical. The hard-won shift towards the ‘elementary’ stage promised a change, but the new education policy document and NCFFS indicate that the movement towards elementary education is unlikely to be supported. Other stages of education are similarly perceived in a fragmented way. If each stage of school education is going to be covered in the style of this document, we can expect over one thousand pages of unhelpful prolixity.

A curriculum framework is supposed to be an enabling document. If it is to be useful, the intended readership must be taken into account. If teachers are part of that readership, their daily struggles and achievements under highly diverse conditions should find reflection. Alas, teachers are far too remote from the concerns of people who prepare policy documents. Our system considers prescribed textbooks as a sufficient resource for the teacher.

Moreover we hear that teachers will be monitored by technology. Their autonomy is of zero value to the authorities and school managers, fond of uniformity. They believe that uniformity is the key to quality. Such belief offers little scope for confidence in the teacher. Every effort is made to keep teachers under a tight grip every hour of the day. A teacher who is so regimented can hardly nourish an autonomous mind in the child, no matter what the subject.

(Dr. Krishna Kumar is a former director of NCERT and NCTE and author of Smaller Citizens (2021))