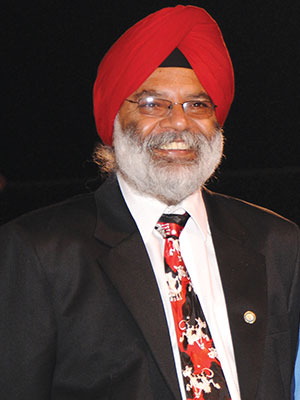

– Capt. AJ Singh is director, Pinegrove School, Dharampur and former Chairman, Indian Public Schools’ Conference and Member, Board of Governors of the CBSE

– Capt. AJ Singh is director, Pinegrove School, Dharampur and former Chairman, Indian Public Schools’ Conference and Member, Board of Governors of the CBSE

Understandably, affluence of the middle class has raised aspirations for a ‘good’ education that has become an essential prerequisite. The rising aspirations, a twisted vision of education, skewed ideology and populist policies, are leading to an impasse. The onslaught of Covid and the after effects of the unending court battles, between parent and school associations, have only added to the predicament. This unnecessary confrontation is leading to a standoff between the legality of fee regulation vis-à-vis fee stipulation or fixation.

Since independence, unaided private schools have extensively proliferated due to the quality they provide and the failure of the Indian State to provide acceptable standards but are being widely envisioned as ‘commercial’ entities. It may be true that actions, and conduct of some schools may not have brought grandeur and pride to the profession. Unreasonable raise in fee, charges levied on small pretexts, capitation, exploitation of teachers etc. add up to breed resentment and bitterness. True purpose of education and philanthropy is being sidelined for opulence and snob-value. The frustrations of the middle class and the angst against the lack of good government institutions have, over time, infuriated people who have trained their guns on private schools. Various state governments, with a view to placate their electorate, have acted in haste and started looking for ways to regulate and fix fee.

While regulation of malpractices is important, laws need to be made without encroaching on existing provisions or trampling upon fundamental rights. The byelaws of various school boards, Education Codes and Rules, Registration of Societies Act, Indian Trusts Act, Companies Act, RTE Act and the Income Tax Act, have all got a strong stranglehold on the operation of schools. Indian law permits only registered “not-for-profit” (NPO) charitable organizations to run schools. A layman, comprehends that a school should not be making any profit, while an NPO actually means that all profits need to be used for the purposes and growth of education and are not to be shared or distributed among promoters, except ‘reasonable’ payments made for service provided. Every school needs to comply with the laws of getting their accounts audited, filing tax returns, providing information to the authorities regarding facilities and teacher quality, fulfilling all other statutory requirements and admitting under-privileged students under the RTE Act.

Hence, there’s a catch-22 situation. The public wants the best facility with restriction on costs, while school managements desire a reasonable return on investment, speedy growth, autonomy and freedom, as enshrined in the Constitution and interpreted by the Supreme Court in various judgments most prominent of which is the 11-judge bench decision in TMA Pai Foundation Case which preserves the right of unaided private schools to decide their own fee structures, while upholding the right of the State to stop ‘profiteering’ in schools and allowing governments to fix fee structures in higher education (professional colleges) only.

Despite the existence of occupied fields in law and in their eagerness to control there appears to be a lack of intelligible interpretation of the existing provisions of law. Gujarat, Rajasthan, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and the recently drafted bill in Himachal Pradesh have attempted not to regulate but have aimed to micro-manage, control, inspect, fix and stipulate fee and increase thereof.

‘Profiteering’ and ‘commercialization’ have a negative connotation and are illegal. Adequate penal provisions already exist, for such activities, like levying penalties, withdrawal of exemptions or even cancellation of registration/NOC/affiliation and state governments are failing miserably in elucidating the difference between making profit and profiteering, receiving legitimate donations and capitation, genuine educational pursuits and ‘commercialization’.

A parent makes a choice to send a child to a particular unaided school after evaluating the standard and price, so the protest can, logically, be about the “increase in fee” and not the fee per se. Govts already have the authority to enforce transparency and make schools announce their fee two-three months before the new session. When government salaries and allowances are correlated to inflation and pay commissions and development needs of a private institution cannot be determined by the executive, then it makes no legitimate sense to stipulate a fixed percentage increase in fee, without linking it to inflation, pay commissions or institutional growth.

Notwithstanding, the fact that there may be some unscrupulous elements, the majority of schools in India are serving society at costs less than the government’s average cost-per-child. A presumption that every unaided school, whatever be its nature, is guilty of malpractices and therefore must justify its fee, every year, seems prejudicial. School authorities are left to deal with the pressure tactics of some disgruntled parents, while the silent majority will ultimately suffer the long-term consequences of demotivation and expected degradation.

Surprisingly, parents are never seen protesting to ensure the rights of their child’s teacher. For obvious reasons, education is not attracting the best available human resource in India. The social status of teachers is deteriorating by the day and we, as a people, are contemplating stifling the aspirations of the education sector. The highly honoured ‘guru’ of yesteryears, to whom a ‘guru-dakshana’ was happily offered, is fast losing respect. Governments need to opt to improve the lot of teachers in private schools and develop their own schools, to a standard, where the public has a fair choice between free and paid education.

School federations have started knocking the doors of the Supreme Court, which in its interim judgement (314/2018) staying the Gujarat Regulation of Fee Act, ordered that “The state of Gujarat shall not question the decision of any school to provide a particular facility or things in a particular quality or standard which it considers appropriate for imparting education in its school. The Schools would be entitled to fix their fee structure to meet the cost of providing such facilities or standards.”

While it is the absolute right of the government to regulate and administer educational institutions, to prevent maladministration and ensure excellence in education, fee determination is the unqualified right of private unaided institutions. If legal narratives are not made equitable, flawed laws will get challenged and the Supreme Court will need to step in, once again, to protect and safeguard the future of school education.

Also read: 25 Leaders reinventing K-12 education – Captain A.J. Singh