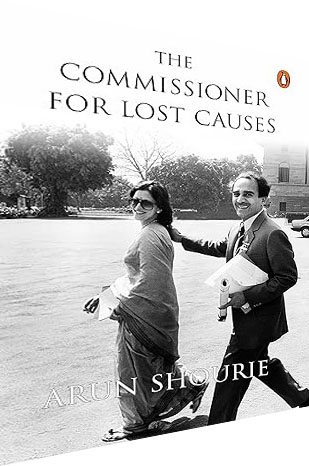

The commissioner of lost causes

The commissioner of lost causes

Arun Shourie

penguin random house

Rs.619

Pages 582

An account of the author’s tumultuous years as Editor of the Indian Express under its legendary publisher Ramnath Goenka

To citizens of a certain vintage who have outlived their prescribed lifespan of threescore and ten, and who remember the era before television and social media when the press was the sole purveyor of news and learned opinion, Arun Shourie, a former World Bank executive who was parachuted to the top as editor of the Indian Express in the post-Emergency era, is a legend. In short time he transformed newspaper journalism from a genteel profession in which grave, pipe-smoking editors with Oxbridge credentials dictated learned, balanced editorials which were accorded high respect, into an iconoclastic medium which went after government and politicians with ferocity and tenacity.

This memoire is an autobiographical account of Shourie’s tumultuous years as Executive Editor of the Indian Express under its equally legendary publisher/proprietor Ramnath Goenka (1904-1999) who earned himself a place of honour in the Hall of Fame of Indian Journalism as the only newspaper proprietor who stood up to prime minister Indira Gandhi when she declared post-independence India’s sole and infamous internal Emergency (1975-1977).

The volume starts with Shourie’s dissatisfaction with his prized job at the World Bank in Washington D.C. How he landed this coveted job, is not recounted. The author had just got married and Washington was a very “fine green place”. The job involved travelling to many countries. “But all our relatives were in India and all my interests were in and about India.” After intensive searching for opportunities, he landed a Homi Bhabha scholarship plus a consultancy at the Planning Commission, at Rs.500 per month.

In the early 1970s, the Soviet-style Planning Commission was dominated by “Mrs. Gandhi’s circle of Kashmiris” in which “everyone of significance liked to think of himself as being to the Left of everyone else”. Soon enough Shourie was obliged to resign from the commission, and luckily got his job back at the World Bank thanks to his friendship with Pakistani economist Mahbub-ul-Haq.

Back in Washington, it’s a measure of the man that instead of thanking his stars that he was safely abroad when Mrs. Gandhi declared the Emergency in 1975, Shourie was “even more determined to return to India,” and he gave notice to the Bank despite his son Adit being born with a brain injury. During his notice period, after much effort he landed a job as a senior fellow at the Indian Council for Social Research, and the Shouries moved into his father’s home in Delhi.

After returning to Delhi in the midst of the Emergency, Shourie began writing opinion essays for Seminar, one of the few publications “continuing to write independent stuff”.

An essay titled ‘Symptoms of Fascism’ prompted the voluntary closure of Seminar rather than the publishers — well-known intellectuals Romesh and Raj Thapar — submitting to pre-censorship as required by Emergency regulations. The essay was nevertheless cyclostyled and circulated to politicians jailed by Mrs. Gandhi, and led to an introduction to Ramnath Goenka proprietor/publisher of the Indian Express, the sole newspaper that defied censorship rules during the 19-month Emergency. Thus began a seesaw publisher-editor partnership that totally transformed Indian newspaper journalism and prompted the post Emergency magazines boom.

In the pre-Shourie era, long form campaign journalism conducted on the front pages was unknown in mainstream media, and anti-establishment magazines didn’t exist. All that changed after Shourie was plucked out of obscurity and appointed Executive Editor of the multi-edition Indian Express in 1978.

Suddenly, as he recounts in this engrossing autobiography, facts became more important than opinions, young reporters started getting bylines and the tradition of reporting sensational news or scandals one day and forgetting about them afterwards went out of the window.

Shourie’s practice and direction to his reporters was “unearth the facts, and just don’t let go”. Starting with exposure of government holding thousands of undertrials in jails across the country, the Express mounted a sustained nationwide campaign exposing their pitiful condition that scarred the national conscience and forced the Supreme Court to issue elaborate guidelines and ensure that bail rather than jail became the norm. Next he took up the cause of some suspected criminals who were deliberately blinded by the police in Bhagalpur, Bihar.

In turn this led to questioning the equanimity with which the justices of the Supreme Court presided over a clearly dysfunctional judicial system, and “discordance” between its oft expressed anguish about the blatant violations of citizens’ rights and its inaction in punishing officials of the State. Later this led to an exposure of Supreme Court judge PN Bhagwati who was roundly pilloried for passing contradictory judgements, and his famous letter to Mrs. Gandhi after she was returned to power at the Centre in 1981, in which he gratuitously likened her return to the “reddish glow of the rising sun”.

In his 12-year career in the Express, Shourie exposed the corruption and abuse of office of the highest and mightiest in the land. Among them: Rajiv Gandhi for his involvement in the Bofors gun import scandal; “trader in unions” Datta Samant who shut down the Express offices in Mumbai for weeks; successfully aborted Rajiv’s press gag defamation Bill and took on the old-style “popes” (editors) of established newspapers; outed the corruption of Maharashtra chief minister Abdul Rehman Antulay for running a cement distribution scandal, and laid low several other sawdust caesars who strutted the national and regional stages in those tumultuous years. For all this, he made many enemies and was sacked from the Express, and worked for a while in the Times of India at a time when Bros Samir and Vineet Jain were cutting editors to size.

All these battles fought by him for probity and accountability in public life are set out in elaborate detail in this engaging memoire. In the process, Shourie’s fearless, iconoclastic journalism catalysed the post-Emergency magazines boom which birthed periodicals such as India Today, Sunday, Business India and BusinessWorld. The latter two publications broke with socialist tradition to lift the corporate veil and transformed vilified capitalists into business and industry heroes.

If there is a downside to the memoire of this messianic journalist and exposer of chicanery, corruption and hypocrisy in high places, it is that Shourie is inclined to indulge in an overkill of his targets. Even after their corruption and misdeeds are exposed beyond all reasonable doubt, he is determined not to let go. This perhaps explains the size of this tome.

Secondly in the interests of authenticity, he is obliged to report all conversations — including words like yes and no — in Hindi written in the Roman script. This makes reading translations a tedious business. But these are minor flaws in this enlightening memoire which one hopes will be supplemented by an account of his years in politics and government.

Dilip Thakore

Also read: World Press Freedom Day: Interview with journalists Josy Joseph and Sandhya Ravishanker