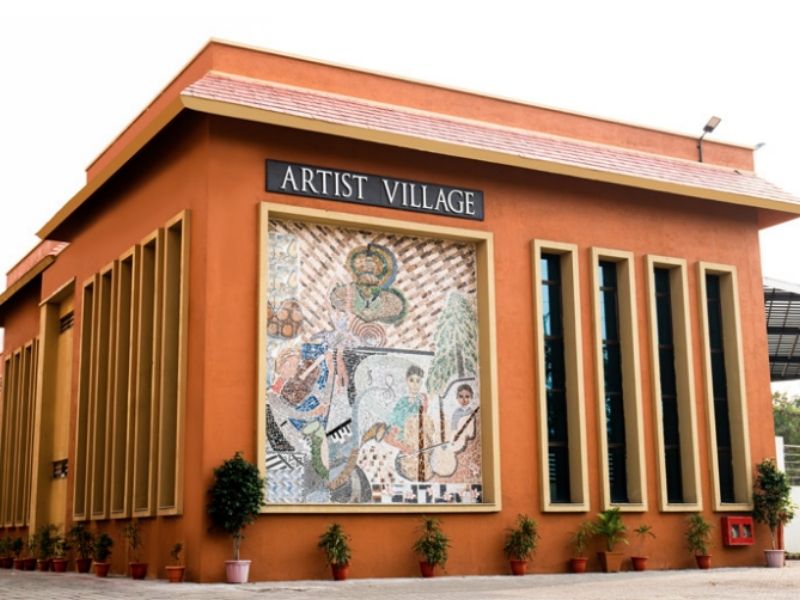

Paradise Gained… The Artist Village DPS Mihan

As I walked towards the Artist Village within the campus of DPS, Mihan, standing sentinel at its entrance was the Tree of Life, conceptualised by renowned Chhattisgarh artist Sushil Sakhuja. Gazing at it spellbound, I wondered if this was the fabled kalpavriksha … the wish-fulfilling tree. Was I in paradise? I realised then that I […]