Cameron Saunders (The Book Review)

One of the most prominently featured characters in Barbara Demick’s new book is called Gonpo. Born in 1950, a year after Mao Zedong declared a ‘New China’, she is the daughter of a King in Amdo, a region on the eastern end of the Tibetan Plateau in what is modern-day Sichuan. When the Red Army arrives later in the 1950s, her father is deposed and sent to Chengdu to be neutralized and re-educated. During the Cultural Revolution, he will commit suicide after his wife, the queen, disappears.

Gonpo, meanwhile, with her bad class background and suspect ethnic status, is sent to the end of the earth — arid Xinjiang — for a decade. There, she will fall in love with a Chinese boy, eventually settling back East in his native Nanjing.

When the liberal 1980s arrive, she becomes a star teacher and then a tool of a Communist Party that seeks to publicise Tibetan success stories. The Panchen Lama, mainland China’s most powerful Tibetan, takes a liking to her and arranges for her study in Dharamshala. While there (with half her family still in China), the Tiananmen Square massacre changes the mood of politics at home. She stays in India, where she can be found today, an elected representative to the Tibetan government-in-exile.

Gonpo’s story is typical of what Demick, a longtime correspondent of the Los Angeles Times, strives to achieve in her work: assembling a cast of characters from a small locale to tell the story of a people as a whole. Her first book, Besieged, followed lives spent on a street in war-torn Sarajevo. Her second, Nothing to Envy, explored the fate of six North Koreans from a coastal city as they struggle to navigate life under the repressive totalitarian regime.

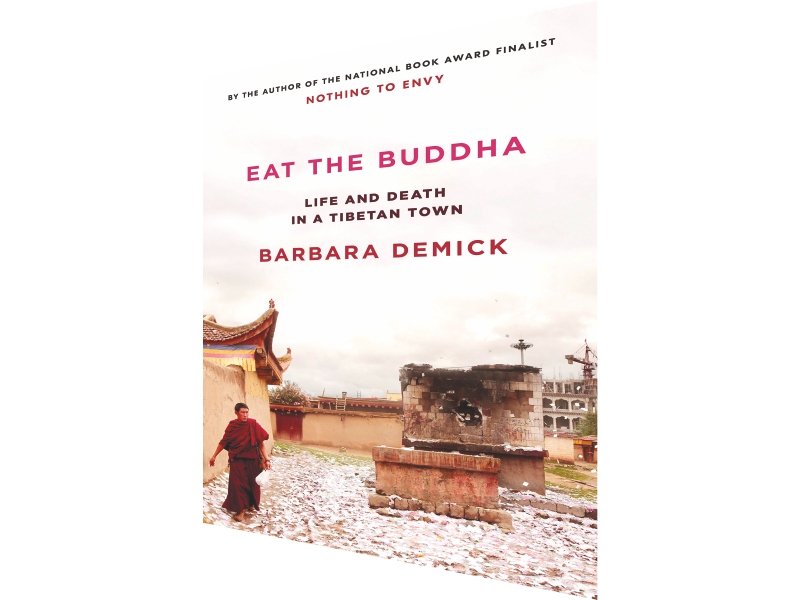

In Eat the Buddha the locale is Ngaba, in Amdo, a town known by the Chinese for its unruliness. A decade ago in a period of exceptional social tension, it earned the dubious appellation of the self-immolation capital of the world.

Following lives that revolve around this municipality — teenage monks from the local monastery, nomads moving about its outskirts, scrappy entrepreneurs quick to embrace the market economy, a princess — Demick gives us a history of this town and, by extension, of Tibet as a whole.

A pawn of the British in the days of the Great Game, after dissolution of His Majesty’s empire following the end of the Second World War, Tibet finds itself without a patron (unlike, say, the Mongolians who had the Soviets to shepherd them into statehood), and as a result, subject to an emboldened, highly militaristic Maoist China bent on expansion and consolidation. The new government in Beijing, after initially playing nice, soon exposes its duplicity and brutality. All of the tragedies of the early decades of Communist China — trigger-happy Red Army revolutionaries, the Great Leap Forward famine, and the Cultural Revolution — are experienced by Tibetans in wanton suffering.

The liberalisation of the 1980s offers some relief, but, as market reforms kick in and China becomes rich and assertive, Tibetans are at the losing end. They are distrusted ethnic minorities, discriminated against in an overwhelmingly Han country. Encouraged by Beijing, Han settlers move in from the East, enriching themselves on the wealth of the Plateau as they ease population pressure in their traditional heartlands. Tibetans, overwhelmingly subdued, watch all this with a growing sense of agitation and awareness of their own poverty.

Demick warns against indulging an Orientalising fantasy. Too often, Tibetans are seen by outsiders — especially in the West — as rosy-cheeked nomads who, with their horses, yaks and tents, live pure lives dedicated to religious enlightenment. Such a denial of modernity is utterly false; the truth is less rosy.

The hope for economic prosperity comes with all the trappings and aspirations of young people in a globalised culture: blue jeans, mobile phones, and (as Barbara Demick often notes when reporting from inside Tibetan homes) posters of pop stars adorning walls.

Besides a fair shake economically, the freedom to practice their religion unimpeded by Chinese meddling is a pivotal concern for Tibetans. The Communist regime perennially denounces the revered Dalai Lama as a separatist criminal and is relentless in trying to reshape Tibet’s ancient Buddhist traditions in its own new mould. Unsurprisingly, this leads to insurrectionist strife.

In 2008, an uprising was brutally crushed. Later that year, the self-immolations began — mostly, but by no means exclusively, the final desperate acts of young monks resident in local monasteries. Over a hundred occur before they taper off several years later.

Now Beijing’s sights are set on the peripheral autonomous provinces: Inner Mongolia, where the school curriculum was changed last year from half Mongolian to fully Chinese; Xinjiang, where up to a million Turkic-speaking Uighurs are currently incarcerated in re-education camps; and finally, Tibet, the subject of this book, and a region where the pressure is unceasing.

Also read: Tale of two nations: India’s China challenge