The major understated casualty of the massive damage caused by the globally rampaging Coronavirus pandemic are India’s 500 million youngest citizens in 0-24 age group. But the recently presented Budget 2021-22 has provided no relief for the world’s largest and most high-potential child and youth population – Dilip Thakore

Unsurprisingly, the prime objective and focus of the Union Budget 2021-22 presented to Parliament and the nation on February 1 by finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman — the first pandemic year budget of the BJP/NDA government — was to get the economy back on track and re-fire the engines of industry and commerce.

Although it seems so long ago, only 11 months have elapsed since a national emergency was declared to prevent the rapid spread of the Coronavirus, aka Covid-19 pandemic that originated in Wuhan (China) in November 2019. On March 25, 2020 a total lockdown of industry, business, public transport services and all education institutions nationwide was declared by the Central government in New Delhi.

“Honourable Speaker, preparation of this Budget was undertaken in circumstances like never before. We knew of calamities that have affected a country or region within a country, but what we have endured with Covid-19 through 2020 is sui generis. When I presented Budget 2020-21, we could not have imagined that the global economy, already in the throes of a slowdown, would be pushed into an unprecedented contraction,” said Sitharaman presenting her third budget after she was unexpectedly transferred from the Union defence to the finance ministry in 2019.

“Honourable Speaker, preparation of this Budget was undertaken in circumstances like never before. We knew of calamities that have affected a country or region within a country, but what we have endured with Covid-19 through 2020 is sui generis. When I presented Budget 2020-21, we could not have imagined that the global economy, already in the throes of a slowdown, would be pushed into an unprecedented contraction,” said Sitharaman presenting her third budget after she was unexpectedly transferred from the Union defence to the finance ministry in 2019.

Unquestionably, the damage caused by the highly contagious pandemic has been enormous. Thus far (February 25), this rampaging virus has infected 111 million people worldwide and caused 2.4 million fatalities. In India, it has infected 11 million and prompted an estimated 157,000 fatalities.

Following detection of the first cases in India last February, in an urgent national broadcast at 8 p.m on March 24, prime minister Narendra Modi declared a national lockdown from the midnight of March 24, reportedly the most stringent pandemic-induced lockdown of any democracy worldwide. The short four hours notice given to the public provoked the largest exodus of suddenly unemployed rural migrants — their number variously estimated at 20-25 million — on foot and private transport (because all public transportation was discontinued from the midnight of March 24) since the partition of British-ruled India into the independent nations of India and Pakistan in 1947.

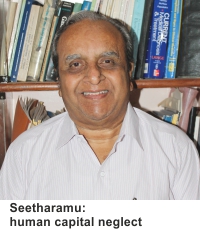

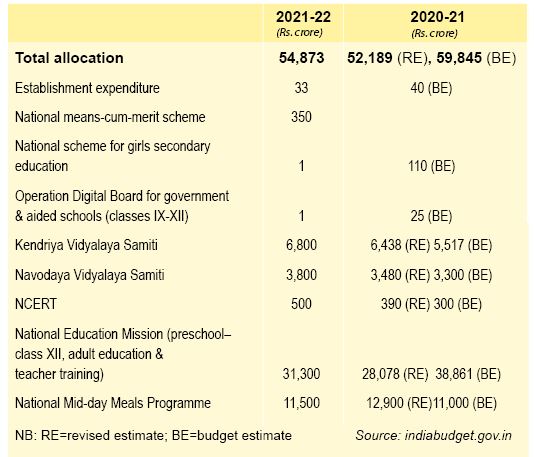

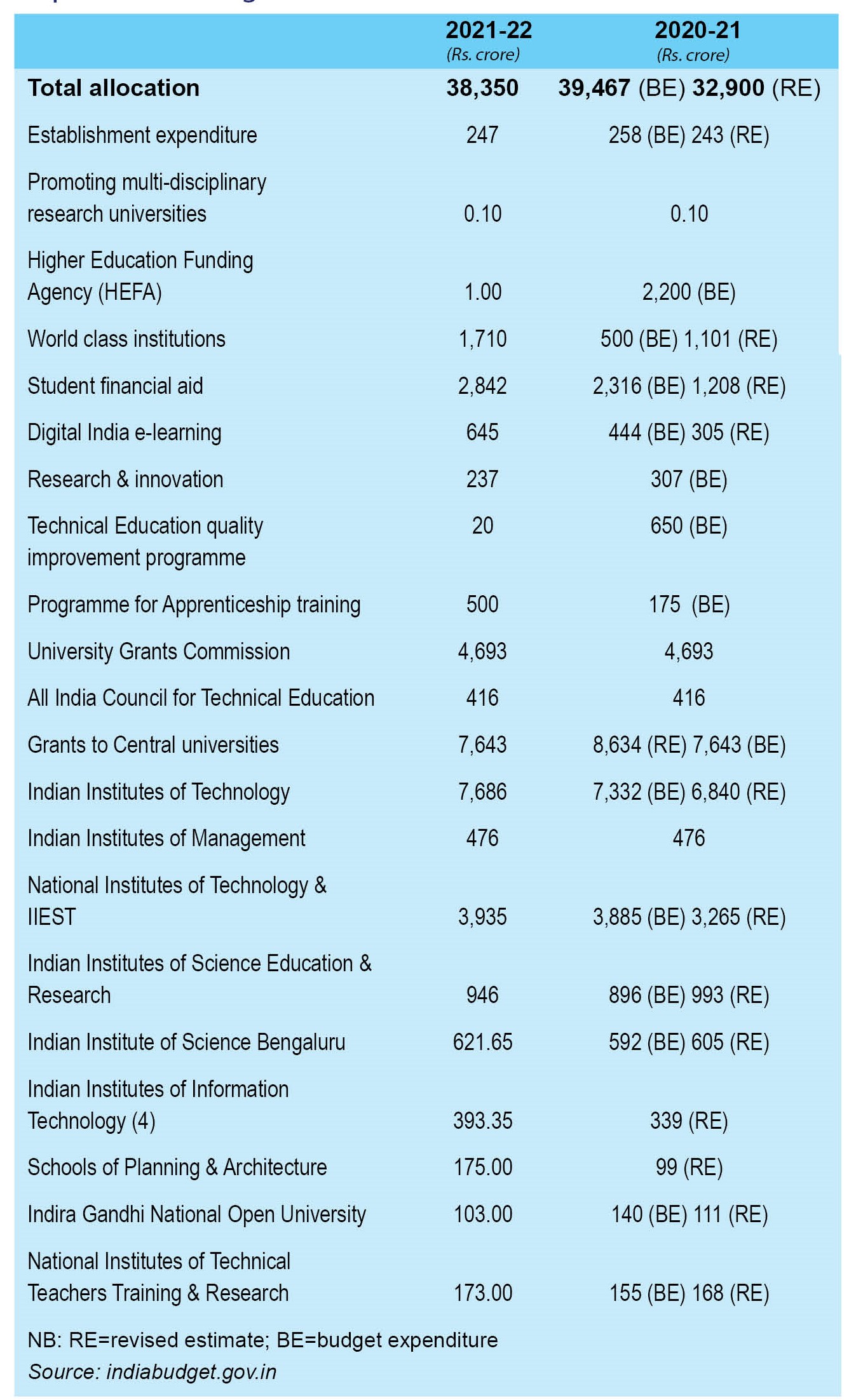

Against this backdrop of national turmoil, a major under-stated casualty are 21st century India’s 500 million youngest citizens in the 0-24 age group — the world’s largest national cohort of children and youth. The total outlay of the Central government for public education budgeted at Rs.93,224 crore for 2021-22 is 6.13 percent less than the Rs.99,312 crore budgeted for 2020-21. And the consensus within the academic community is that Budget 2021-22 has comprehensively ignored the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, the outcome of hard slog of two high-powered committees — T.S.R. Subramanian (2016) and Dr. K. Kasturirangan (2018) — which was promulgated with much fanfare on July 29 last year.

Inevitably, the comprehensive lockdown of business, industry and commerce for almost half the financial year 2020-21 has turned government tax revenue projections topsy-turvy. The Centre’s direct and indirect tax revenue has plunged from the budgeted Rs.20.20 lakh crore to Rs.15.55 lakh crore (revised estimate) in the year ending March 31, 2021. As a result, borrowings in 2020-21 have ballooned from the budgeted Rs.7.96 lakh crore to more than double at Rs.18.48 lakh crore, and the Union government’s fiscal deficit has rocketed from the budgeted 3.5 percent of GDP to an unprecedented 9.5 percent of GDP (gross domestic product) estimated at Rs.195.86 lakh crore cf. the budgeted Rs.224.89 lakh crore.

In this connection, it’s pertinent to note that the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act, 2003 requires the Union government to ensure its fiscal deficit in any financial year does not exceed 3.5 percent of GDP, although it allows exceptions in special circumstances. This legislation piloted by former Union finance minister Yashwant Sinha to compel the Central government to maintain macro-economic stability and contain inflation, is self-explanatory. If government borrows unlimitedly from the Reserve Bank of India — i.e, prints bank notes without commensurate increase in the output of goods and services — too much money will start chasing too few goods and result in runaway inflation which, it is commonly accepted, hits the poor at the bottom of the socio-economic pyramid hardest. However, the exceptional circumstances latitude has given a wide loophole to government. Since it was enacted almost two decades ago, the FRBM Act ceiling has not been respected in spirit by any government at the Centre with considerable expenditure being made ‘off-budget’.

But with the Covid-19 mayhem and resultant lockdown causing the economy to contract by 8 percent — the worst recession in the history of post-independence India — and a steep fall in tax revenue, finance minister Sitharaman had no option but to slash government expenditure under several heads to contain the fiscal deficit which has soared to Rs.18.48 lakh crore (9.5 percent of GDP) in 2020-21 to reduce it to Rs.15.06 lakh crore (6.8 percent of GDP) next year.

Not surprisingly given the low priority given to human capital development by post-independence India’s political class, the bureaucracy and compliant establishment, including the academy, the axe has been applied to the social welfare sector, and education in particular.

This time round because of the pandemic, the Centre’s outlay for public health has been raised to Rs.2.23 lakh crore in 2021-22 from the budgeted Rs.94,452 crore (and the actual revised estimate of Rs.78,866 crore) of 2020-21. Consequently, education has had to bear the brunt. The Centre’s outlay for public education has been reduced by Rs.6,088 crore from Rs.99,312 crore budgeted for 2020-21 to Rs.93,224 crore (revised to Rs.85,089 crore) in 2021-22.

To reignite the engines of business, industry and commerce, the finance minister and North Block bureaucrats have gambled on heavy capital investment in public infrastructure — according to Dr. Krishnamurthy Subramanian, chief economic advisor to the Union government, a rupee invested in public infrastructure adds Rs.2.5 to GDP.

Nevertheless liberal economists believe that investment in human capital development should have been given equal — if not greater — attention in Budget 2021-22 because the national lockdown, and especially comprehensive closure of all education institutions from pre-primaries to universities countrywide, has hit youngest children in the 0-8 age group very hard.

With the country’s estimated 55,000 private preschools and 1.6 million free-of-charge anganwadi centres (AWCs), essentially nutrition centres for lactating mothers and newborns which also provide rudimentary early childhood education to 85 million children in the 0-6 age group from the poorest strata, closed, an estimated 90 million youngest children are in grave danger of forgetting what they’ve painstakingly learned. Moreover, 85 million infants are in danger of experiencing malnutrition because AWCs also provide a free mid-day meal to their children (see EW February 15 cover feature https://www.educationworld.in/pandemic-thunderbolt-endangers-early-years-education/).

In the circumstances, not a few educationists believe that special provision to make good the massive learning deficit and well-being of youngest children should have been made by Sitharaman. Instead, the outlay for the Centre’s Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan (pre-primary to higher secondary) schooling has been slashed from the Rs.38,860 crore budgeted for 2020-21 to Rs.31,300 crore next year.

“The Union Budget 2021-22 is unimaginative and lacklustre. While it has increased capital expenditure on infrastructure by 34.5 percent, the finance minister has reduced expenditure on human capital development which is as — if not more — important. In Budget 2021-22, the Centre’s outlay for education has been reduced by Rs.6,000 crore at a time when the digital divide between students in private and government schools has been exacerbated. Over 40 percent of in-school children have been denied online education during the pandemic. If due to prevailing constraints, the BJP/NDA government couldn’t provide for the education of the country’s children, the least it could have done was to invite private sector investment. Ultimately it is the interest of children that is paramount.

Government should have used this occasion to acknowledge the important role of affordable budget private schools in raising teaching-learning standards in primary-secondary education and invited their cooperation. Children are the future of the nation. Therefore, everything possible has to be done to ensure that their education continues one way or the other. Budget 2021-22 has shown no awareness of this,” laments Dr. A.S. Seetharamu, former professor of education at the Institute of Social and Economic Change, Bengaluru (ISEC, estb.1974) and currently education advisor to the Karnataka government.

Government should have used this occasion to acknowledge the important role of affordable budget private schools in raising teaching-learning standards in primary-secondary education and invited their cooperation. Children are the future of the nation. Therefore, everything possible has to be done to ensure that their education continues one way or the other. Budget 2021-22 has shown no awareness of this,” laments Dr. A.S. Seetharamu, former professor of education at the Institute of Social and Economic Change, Bengaluru (ISEC, estb.1974) and currently education advisor to the Karnataka government.

That the education, health and well-being of the world’s largest child and youth population has been callously ignored in Budget 2021-22, is a widely shared sentiment among knowledgeable monitors of the Indian economy. The outlay for the Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan (SMA, public pre-primary to higher secondary school education) has been slashed by 20 percent to Rs.31,050 crore, and for the free schools mid-day meal programme by 12.1 percent from the actual amount (revised estimate) of Rs.12,900 crore spent in 2020-21 to Rs.11,500 crore next year.

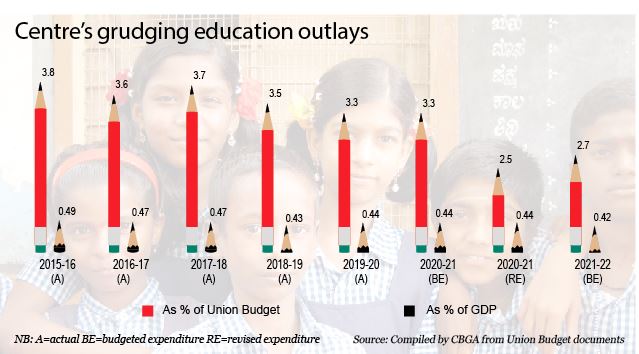

Although ex facie against the backdrop of sharply fallen tax revenue and higher expenditure forced by the Covid crisis plus 19 percent higher defence outlay (excluding pensions) prompted by the China threat on the north and north-eastern borders, Union finance minister Sitharaman didn’t have much headroom to make additional provision for public education, Subrat Das, president of Delhi-based think tank Centre for Budget Governance and Accountability (CBGA, estb.2002), believes the minister was “too cautious” about limiting the 2021-22 fiscal deficit. In his opinion, she should have increased the allocation for public education to address the “vitally important issues” of bridging the newly emergent digital divide between children in private and government schools, and to implement NEP 2020, even at the cost of enhancing the fiscal deficit.

Although ex facie against the backdrop of sharply fallen tax revenue and higher expenditure forced by the Covid crisis plus 19 percent higher defence outlay (excluding pensions) prompted by the China threat on the north and north-eastern borders, Union finance minister Sitharaman didn’t have much headroom to make additional provision for public education, Subrat Das, president of Delhi-based think tank Centre for Budget Governance and Accountability (CBGA, estb.2002), believes the minister was “too cautious” about limiting the 2021-22 fiscal deficit. In his opinion, she should have increased the allocation for public education to address the “vitally important issues” of bridging the newly emergent digital divide between children in private and government schools, and to implement NEP 2020, even at the cost of enhancing the fiscal deficit.

Union Budget 2021-22: Major education allocations

Department of School Education & Literacy

“Admittedly because of the pandemic situation which has reduced the Central government’s tax and other revenue, the fiscal deficit has risen way beyond the 3.5 percent of GDP prescribed by the FRBM Act. But this is mainly because several off-the-budget expenditures — especially the sizeable deficit of the public sector FCI (Food Corporation of India) — have been brought on the books. This has been done to reflect the true magnitude of the fiscal deficit in the interests of transparency. It’s not because of heavy new expenditure. In this extraordinary year of the pandemic, it would have been preferable to maintain the status quo and make the substantial investment required in education to implement NEP 2020, and bridge the digital divide between children of private and public schools. The plain truth is that children — especially girl children — from EWS (economically weaker sections) households don’t have access to digital and online learning. This is certain to widen the rich-poor gap and exacerbate gender inequality across the country. Budget 2021-22 should have made greater provision for investment in digital infrastructure for government schools and for sanitising and preparing them for early re-opening, providing an example for state governments — which also have responsibility to improve the public education system — to follow,” says Das, an economics postgrad of Delhi’s show-piece JNU who was appointed president of CBGA in 2010.

Most development economists and pundits concede that with the national GDP set to contract by 8 percent in fiscal 2020-21 because of the pandemic lockdown and the Centre suffering a massive drop in tax revenue with no scope for raising taxes, Sitharaman had no option but to axe spending under some heads, including public education.

However it’s a mystery why the professedly pro-free enterprise and free markets BJP leadership unencumbered by the socialist baggage of the Congress party, hasn’t invited private investment in the education sector to take up the slack. Surely the government is aware that as testified by the path-breaking State of Sector Private Schools in India Report, 2020 of the Central Square Foundation, 47.5 percent of all school-going children are already in private schools, and government schools are the default option of poorest households that cannot afford even the rock-bottom tuition fees of the country’s unique 400,000 budget private schools which are educating 60 million children. Given the financial strait-jacket of Covid-19, the finance minister could have at the very least, smoothed the way for greater inflow of private investment into the beleaguered education sector.

Union Budget 2021-22: Major education allocations

Department of Higher Education

According to Prof. Geeta Kingdon, chair of education development economics at University College, London and president of City Montessori School, Lucknow, ranked the #1 co-ed day school in Uttar Pradesh (pop.215 million) in the EducationWorld India School Rankings 2020-21, the public K-12 education sector suffers several structural deficiencies that are stifling all learning improvement initiatives of the Central and state governments. Among them, the main one is government’s inability to “balance the teacher-pupil ratio in public schools”. Due to continuous flight of children from government to affordable budget private schools, in some government schools against the 1:30 ratio prescribed by the Right of Children to Free & Compulsory Education (RTE) Act, 2009, the ratio is 1:10. On the other hand, especially better performing urban government schools, it is 1:60.

“If the Central and state governments simply transferred surplus teachers to their under-served schools, the current budgetary allocation would go a much longer way and improve the poor learning outcomes of the country’s 1.20 million government schools. Moreover, the unprecedented contraction of government revenue in the current pandemic year upon BPS (budget private schools) which would make them eligible for debt repayment moratoriums and soft loans for digitisation of teaching-learning. This would save the jobs of over 1 million teachers in this era of high unemployment. This would also have been a good time to introduce direct benefit transfer of the not unsubstantial per-pupil amount spent by government, into the bank accounts of their parents to enable them to choose the best private or government school for their children. This has been advocated by education voucher scheme proponents for quite a while. Such child-centric structural reforms in preschool-higher secondary education are overdue,” says Kingdon.

Indeed given widespread awareness among Indian economists and development scientists — scores of whom have risen to high positions in international institutions such as the World Bank, IMF, and various affiliates of the United Nations — that human capital development is the condition precedent of national development, it’s baffling that modernisation and universalisation of primary-secondary education has been given rock-bottom priority in post-independence India’s national development programme.

The painful truth routinely obfuscated by tub-thumping nationalists, complacent academics and shallow media pundits, is that 70 years after independence and formulation of 13 detailed five-year plans by subservient economists, contemporary India hosts the world’s largest number of comprehensively adult illiterates (300 million); 56 percent of children in rural (especially government) primaries cannot read class II textbooks and/or solve simple arithmetic sums; only 69 percent of children enter higher secondary school and the GER (gross enrolment ratio) in higher education is a mere 30 percent (cf. 84 percent in South Korea) and industry, agriculture and government productivity is among the lowest worldwide.

The root cause of this dismal scenario is that despite several high-powered commissions and committees starting with the Kothari Commission (1967) having recommended investment of 6 percent of GDP in public education, for the past six decades it has averaged 3.25 percent. Consequently, government schools have become notorious for crumbling infrastructure, multi-grade classrooms, English language aversion, wonky teacher-pupil ratios and pathetic learning outcomes.

These factors have coalesced to provoke an exodus of children from free-of-charge government schools into 400,000 fees-levying budget private schools (BPS). Yet instead of reforming and upgrading the country’s 1.20 million government schools, successive Central and state governments have brazenly restricted the promotion of private schools, especially BPS.

According to the Central Square Foundation’s Private Schools in India Report 2020 referred to above, establishing a greenfield private school in Delhi state requires submission of 125 documents in approved formats to be cleared by 40 officials in the state government’s education ministry. Moreover, almost all state governments have imposed arbitrary tuition fee ceilings on private schools. During the pandemic instead of providing financial aid and assistance to private schools that have switched to online learning, they have advised parents to desist from paying duly contracted fees even while mandating payment of teachers’ salaries. As a growing number of private schools, particularly pre-primaries and BPS shut down across the country, the biggest losers will be the 119 million children enrolled in them and millions of teachers thrown out of employment.

With Budget 2021-22 having made no special provision for continuing education of the world’s largest child and youth population and discouraging philanthropic and for-profit investment in education, the country’s much-trumpeted demographic dividend is rapidly transforming into a demographic disaster, as armies of youth unqualified for the demands of 21st century workplaces are streaming out of sub-standard education institutions to swell the ranks of the unemployed.

Intelligent monitors of India’s languishing education sector are particularly disappointed that the BJP government which is unencumbered by the socialist baggage of the Congress Party, is as indifferent, if not hostile, to liberalisation and deregulation of Indian education. A possible reason could be the influence of the RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh), the shadowy, ideological mentor organisation of the BJP. Enamoured with the glories of pre-Mughal era Hindu history of the subcontinent and unable to separate mythology from history, the RSS leadership is as determined as the Congress to maintain strict government control of the education system, and in particular rewrite history and social science textbooks from the hindutva perspective.

Intelligent monitors of India’s languishing education sector are particularly disappointed that the BJP government which is unencumbered by the socialist baggage of the Congress Party, is as indifferent, if not hostile, to liberalisation and deregulation of Indian education. A possible reason could be the influence of the RSS (Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh), the shadowy, ideological mentor organisation of the BJP. Enamoured with the glories of pre-Mughal era Hindu history of the subcontinent and unable to separate mythology from history, the RSS leadership is as determined as the Congress to maintain strict government control of the education system, and in particular rewrite history and social science textbooks from the hindutva perspective.

However, the cataclysmic impact of the once-in-a-century Covid-19 influenza pandemic which has forced the closure of all academic institutions countrywide for over ten months, and threatens extensive loss of learning and associated socio-economic disasters (drop-outs, millions of children prematurely joining the labour force, child marriages, child trafficking and prostitution etc) has transformed these ideological aspirations and debates into irrelevant luxuries. With the Central and state governments unable or unwilling to make meaningful investment in education, the national interest requires liberalisation and deregulation of the dirigiste education system and clearing the decks for private — even foreign investment — in Indian education.

“With the world’s largest child and youth population, India has the potential to provide young highly qualified managers and workers to countries around the world, many of whom have ageing populations. Therefore, several pension funds and social impact investors searching for reasonable 7-8 percent return on capital — returns on savings are relatively very low in developed countries — are eager to invest in India’s K-12 and higher education sectors. However, the law which mandates that all education institutions must necessarily be not-for-profit and the over-regulation of education are major disincentives. Quite clearly, the country’s K-12 public education system has failed to meet the needs of children and adolescents. Therefore, the national interest demands education reforms which facilitate and enable private edupreneurs and organisations to promote schools and higher education institutions. This is not to say that government doesn’t have a regulatory role. For instance, the kingdom of Dubai is  dominated by for-profit private education institutions. But they are strictly monitored, inspected and ranked according to several parameters by the Knowledge & Human Development Authority, a government agency, and annual fee hikes are calculated on the basis of inspection, a parents satisfaction survey, academic performance of students linked with an Education Inflation Index. Similarly we need to encourage domestic and reputable offshore private education providers into India by establishing transparent, but light school and higher education regulation guidelines,” says Rakesh Gupta, managing partner of LoEstro Advisers LLP, a Hyderabad-based education consultancy (estb.2018).

dominated by for-profit private education institutions. But they are strictly monitored, inspected and ranked according to several parameters by the Knowledge & Human Development Authority, a government agency, and annual fee hikes are calculated on the basis of inspection, a parents satisfaction survey, academic performance of students linked with an Education Inflation Index. Similarly we need to encourage domestic and reputable offshore private education providers into India by establishing transparent, but light school and higher education regulation guidelines,” says Rakesh Gupta, managing partner of LoEstro Advisers LLP, a Hyderabad-based education consultancy (estb.2018).

Gupta’s assertion that respectable domestic and foreign investors are ready, willing and able to invest in developing India’s abundant and high-potential human capital is backed by the LoEstro Advisers’ impressive track record.

Within three years of promotion, this partnership firm has notched up mergers and acquisition deals valued at Rs.2,500 crore. The company’s blue-chip clientele includes Cognita and Nord Anglia (UK), Cerestra (India), EuroKids, Silver Oaks and Oakdale (Hyderabad) among others. “The urgent need to develop India’s human capital cannot be ignored any longer,” warns Gupta, an alum of the blue-chip IIT-Kharagpur, Indian School of Business, Hyderabad who acquired valuable experience in McKinsey India and People Combine education prior to co-promoting LoEstro Advisors in 2018.

While presenting the difficult pandemic Union Budget 2021-22, finance minister Sitharaman has rightly given top priority to capital expenditure to enhance the country’s physical infrastructure. But education, critical for nurturing the nation’s abundant, high-potential human capital is equally important. With the Centre’s constrained financial condition not permitting meaningful provision for education, Sitharaman should have announced the long overdue liberalisation and deregulation of the cabined, cribbed and confined education system, particularly since the public has made plain its preference for private schools and higher ed institutions.

The national interest demands that the BJP/NDA government initiates an immediate mid-term correction so that the modest hopes and aspirations of the world’s largest child and youth population are fulfilled.

Union Budget 2021-22: Promises sans provision

In her Union Budget 2021-22 address to Parliament and the country on February 1, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced several measures for “reinvigorating human capital”. Among them:

- More than 15,000 schools will be qualitatively strengthened to include all components of the National Education Policy. They shall emerge as exemplar schools in their regions, handholding and mentoring other schools to achieve the ideals of the policy.

- 100 new Sainik Schools will be set up in partnership with NGOs/private schools/states.

- In Budget 2019-20, I had mentioned about the setting up of a Higher Education Commission of India. We would be introducing legislation this year to implement the same. It will be an umbrella body having four separate vehicles for standard-setting, accreditation, regulation and funding.

- Many of our cities have various research institutions, universities and colleges supported by the

government of India. Hyderabad for example, has about 40 such major institutions. In nine such cities, we will create formal umbrella structures so that these institutions can have better synergy while also retaining their internal autonomy. A Glue Grant will be set aside for this purpose.

government of India. Hyderabad for example, has about 40 such major institutions. In nine such cities, we will create formal umbrella structures so that these institutions can have better synergy while also retaining their internal autonomy. A Glue Grant will be set aside for this purpose. - For accessible higher education in Ladakh, I propose to set up a Central University of Leh.

- Standards will be developed for all school teachers in the form of National Professional Standards for Teachers (NPST) for all 9.2 million teachers of the public and private school systems countrywide.

- A unique indigenous toys-based learning pedagogy for all levels of school education will be developed.

- A National Digital Educational Architecture (NDEAR) will be set up within the context of a Digital First Mindset where the Digital Architecture will not only support teaching and learning activities but also educational planning, governance and administrative activities of the Centre and the states/Union territories.

- For children with hearing impairments, the government will work on standardisation of Indian Sign language across the country.

- Senior and retired teachers will be engaged for individual mentoring of school teachers and educators through constant online/offline support on subjects, themes and pedagogy.

- A holistic progress card is envisaged to provide students with valuable information on their strengths, areas of interest, needed areas of focus and thereby helping them in making optimal career choices.

- Online modules covering the entire gamut of adult education will be introduced.

- During the year, despite the Covid-19 pandemic, we have trained more than 3 million elementary school teachers digitally. In 2021-22, we will enable the training of 5.6 million school teachers through the National Initiative for School Heads and Teachers for Holistic Advancement (NISTHA).

- We will introduce CBSE board exam reforms in a phased manner to be effective from the 2022-23 academic year. Exams will move away from rote-learning and students shall be tested on their conceptual clarity, analytical skills and application of knowledge to real-life situations.

- To promote enhanced academic collaboration with foreign higher educational institutions, a regulatory mechanism to permit dual and joint degrees, twinning arrangements and other such mechanisms will be devised.

“However, most of these interventions either do not have any budgetary implications or are not reflected in the budget documents in any form. Similarly, the proposition of strengthening 15,000 schools as ‘exemplar schools’ in their regions towards achieving the goals of NEP 2020, do not have an action, undermining implementation of the proposed initiative,” comment authors of Budget in the Time of the Pandemic — An Analysis of the Union Budget 2021-22 published by Centre for Budget & Governance Accountability, a Delhi-based think tank.

Also read: Budget 2021 slashes funds for nutrition schemes by Rs. 5,000 crore