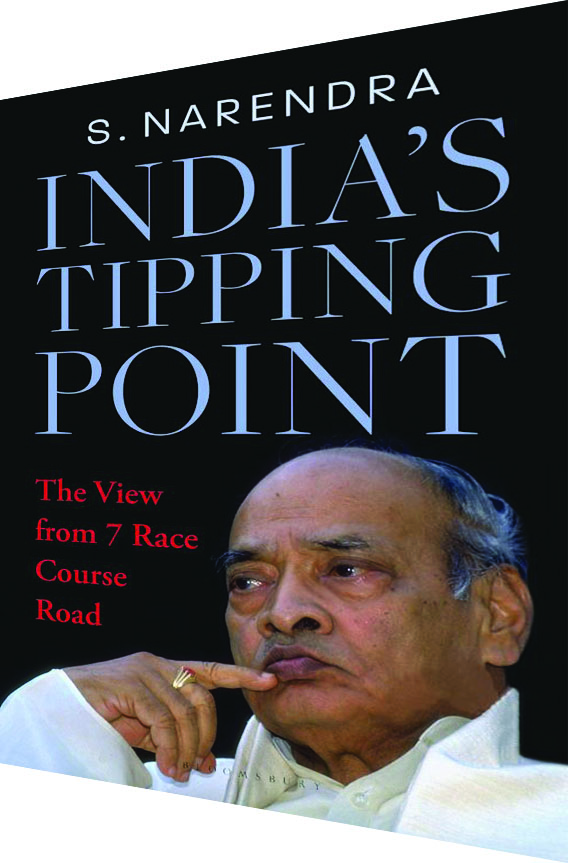

India’s tipping point

S. Narendra

Bloomsbury India

Rs.699 Pages 212

In this biography, the author details how prime minister Narasimha Rao unshackled the Indian economy by stealth

During the past 76 years since India wrested freedom from almost 200 years of British rule, P.V. Narasimha Rao (PVNR, 1921-2004) was undoubtedly the greatest of India’s 14 prime ministers. Although he served only one term in office (1991-96), during those momentous years he substantially won the country’s economic freedom by pulling it out of the mire of neta-babu socialism which had sentenced it to a rock-bottom 3.5 percent GDP growth per year for four decades after independence, and wiped out the modest material aspirations of an entire generation of free India’s children.

This informative biography written by S. Narendra, who as a senior aide of PVNR and principal information officer and adviser to the Union government (1992-98), had a ringside view of those tumultuous years during which the choke-hold of the neta-babu brotherhood on India’s economy was substantially broken, was overdue. It’s a measure of the extent to which the establishment is committed to the status quo ante, that this revealing biography which details the step-by-step dismantling of the licence-permit-quota regime, which had smothered the native spirit of private enterprise and perpetuated poverty and illiteracy in post-independence India, has been ignored by the media and media pundits. The plain truth is that India’s 400-million-strong middle class with deep connections — uncle, brother, nephew — prospering within the brotherhood, isn’t dissatisfied with licence raj. It provides hidden subsidies — inflation-proof salaries, subsidised electricity, water, higher education, pensions — and keeps private businessmen (baniyas) in check.

Highly risk-averse, under the influence of Nehruvian socialism nothing gets the middle class goat more than businessmen prospering and flaunting their money. Which is why even three decades after liberalisation, Congress leader Rahul Gandhi of the Nehru dynasty continues to excoriate India’s most successful entrepreneurs — Ambani-Adani — who have risen from rags to riches for ‘corruption’, i.e, transgression of absurd economic laws enacted by negligent Parliaments down the ages.

The author details how PVNR steered and unshackled the Indian economy by stealth for fear of the academy/establishment. Following Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination in 1991, Rao had been appointed PM with the tacit sanction of his widow Sonia Gandhi, whose expectation was that as a former minister in Rajiv’s cabinet he would be a pliable caretaker PM and toe the socialist line. But this calculation went awry because unlike all previous prime ministers, Rao was genuinely educated.

Jawaharlal, the only Nehru to earn a university degree, scraped through with a third class degree in natural sciences at Cambridge and was totally economics illiterate. However that didn’t stop him from upturning the Indian economy which had a thousand year tradition of free enterprise, and converting it into a “socialist pattern of society”. Central planning meant strangling private enterprise and establishing vast public sector enterprises (PSEs) managed by business-illiterate, risk-averse bureaucrats who quickly ran them into the ground.

This arid socialism continued to be practiced by his daughter and four-times prime minister Indira Gandhi, her son Rajiv and is now being preached by her grandson Rahul. Consequently, the Indian economy was stuck in the 3.5 percent annual GDP growth rate for over 40 years, even as our neighbour South-east Asian economies grew by 6-7 percent, and China by 10 percent year-on-year after Deng Xioping liberalised the Chinese economy in 1978 and famously declared “to be rich is glorious”.

Although obliged to maintain a low profile as minister in Mrs. Gandhi’s and Rajiv’s cabinet, there’s no doubt that Rao — an arts/law graduate of Osmania and Bombay universities — was erudite. He had learnt 17 languages and was well aware of the amazing progress of the Tiger economies of Asia and China in particular, as also of new media in India which routinely trashed licence raj and proclaimed success stories of private enterprises (Business India, BusinessWorld).

Therefore, one of his first initiatives after he became prime minister of politically free, but economically enslaved India, was to abolish the Industries (Development & Regulation) Act, 1951 which required Central government licences to start industrial enterprises and bureaucrats in Delhi and/or the state capitals controlled their expansion, prices and governance.

In retrospect, the radical reforms including devaluation of the rupee and liberalising the Exim policy introduced during PVNR’s five-year term are astonishing, given that simultaneously he had to deal with major political problems including demolition of the “politically explosive” Babri Masjid (1992), the Harshad Mehta scam which upended the stock market (1992), while undertaking several diplomatic initiatives in the Far East. All this and more without upsetting Sonia Gandhi whose mole within the government was the Machiavellian Arjun Singh. Sonia’s support as chief of a faction in the Congress party was necessary for the survival of the PVNR government.

The consensus of opinion is that Rao was a reluctant reformer driven by the IMF and adverse economic circumstances to initiate his path-breaking reforms. The author dismisses this charge head on. Proof was that throughout his term, PVNR retained the industry portfolio to implement his reforms agenda. As a result, annual 6-7 percent GDP growth of the economy has become the new minimum and India’s middle class is the world’s largest and most high-potential market.

But public memory is short and the strategic role PVNR played in placing India on the free markets road is interred with his bones. Had they been continued to their logical conclusion, the radical economic reforms introduced by this accidental prime minister would have placed contemporary India on a par with China. But successive governments at the Centre, including the two-term Narendra Modi government, have failed to sufficiently take the 1991 reforms forward.

Dilip thakore