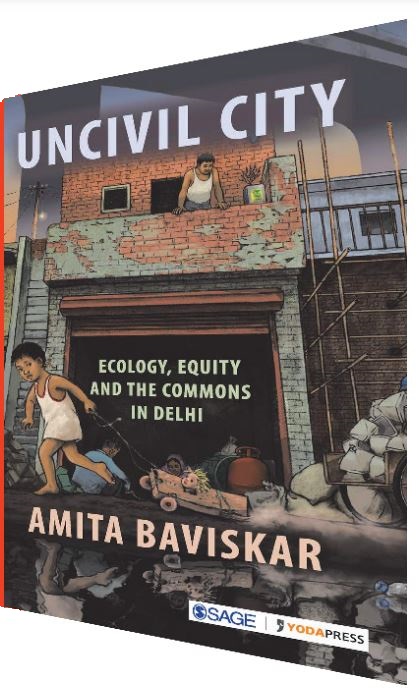

Uncivil city: Ecology, equity & the commons in Delhi

Uncivil city: Ecology, equity & the commons in Delhi

Amita Baviskar; Sage/Yoda

Rs.1,195; Pages 243

– Susan Visvanathan (The Book Review)

Amita Baviskar brings careful and serious considerations to the city of Delhi and its environs, including Gurgaon, giving us revealing insights into this fast-growing urban constellation plagued by toxic pollution. She looks at the way a city is constructed in terms of experiences and events, each in its own way structured by the memories of those who are witnesses to urban and rural transformation.

The megalopolis is defined by the people who live in it. They commute long distances in private or public transport to get to their workplaces and back home again day after day. For Baviskar, these simple routines are telling as she asks questions about them. How do people cope in a metropolis? What happens to the rural hinterland which is continuously appropriated legally or illegally for purposes of residence or for showmanship? To what extent are basic amenities available to people who live in the city? Who are the urban policy makers, and to what extent does global capitalism erode human rights when politicians and the bourgeoisie increasingly begin to see the working class as aliens, migrants who clutter up their cities?

Despite addressing these complex questions, Baviskar manages to shuffle the pack of cards in a way that the data gets organised into neat, readable chapters, even as Orojit Sen’s illustrations provide insightful glimpses into the austere world of abstractions that Baviskar depicts. The author uses spare but engaging prose which occasionally turns chatty, but only to introduce us to an anthropologist’s sense of being part of the picture. It represents a subjectivity which does not detract from the key theme which is, ‘What is our responsibility as citizens to migrant workers?’

We don’t get a detailed description of how Partition created the concentric circles of residence of Delhi, or how history defines segregation of places into Old Delhi, Lutyens Delhi, South Delhi, Yamuna Paar (middle-class professional enclaves across the river). However, for Baviskar, the geography of Delhi includes the adjoining areas of Noida and Gurgaon and it’s so-called ‘nonspaces’ or unrecognised domains. She deals with this adroitly by examining lifestyles, and people are classified not just by their address and locality but also by their mode of transport.

There is a very telling description of rickshaw pullers and their entrenchment in a city which doesn’t recognise the right to life, and their exclusion from its richer pockets. This bloodletting of occupations, which is smugly endorsed by the wealthy as outside the pale of their everyday experience, is the real subtext of the book.

Similarly, Baviskar is keenly interested in understanding how waste management and the lives of people employed as domestic and factory workers, pan out in the city. She describes how the bourgeoisie makes claims to serving the idea of the city superficially in terms of their goodwill and promotion of cleanliness and beauty, but actually through conspicuous consumption contribute hugely to the flotsam of garbage and pollution that is the omnipresent reality of the country’s administrative capital.

By addressing events such as the closure of factories to shunt out workers in the cause of clearing the city of polluting industries, the author takes a clear stand that it is “automobile avarice” that generates the noxious air Delhiites breathe, to a greater extent than any other factor. Anyone who has lived in the environs of factories would know experientially that air does get cleaner when factories move away.

Yet, Baviskar through quantitative analyses proves her case. Her analysis of the Commonwealth Games, the construction of sports stadia and housing enclaves as pride parades that benefit the upper classes is astute, as is her charge that all Delhiites live with the continual show of excess, while hiding the squalor of the poor.

Although everyone talks about it and some are ashamed of this spatial hierarchy, little is done to remove it. Amita Baviskar provides a timely reminder that social conscience, civic sense and justice for the poor must be woven into every discourse of civic management and urban planning. Her attention to climate change, degradation of River Yamuna and the lives of people who live on its banks is a masterly discourse on the connections between environment, ecology and human rights of the poor, which as she demonstrates are non-existent.

In this important book, Baviskar has made an appeal to the social conscience of people to understand that being poor doesn’t necessarily result in dependence and meniality. It is about understanding the hinterland, which when depleted of opportunities forces people to migrate to cities. She seeks to understand why bourgeoisie mentalities are so hardened that they view poverty as an accident of fate and have ill-concealed contempt for those forced into shanties and slums.

The servitude or “disorder” of the poor is the very “order of capitalism” that the Mexican sociologist Manuel Castells discussed 50 years ago in The Urban Question (1979). Urban elites regard it as an opportunity to extract labour of the poor until they are left to die in the most inhumane circumstances.

The Covid-19 pandemic has vividly presented visual imagery of the death-dealing behaviour of employers and landlords, as migrant workers were rendered destitute. What Amita Baviskar with her understanding of the commons, and grasp of the importance of revitalisation of forest lands displays is that in the search for ironed-out parks for the middle class, workers are treated as unwelcome encroachers doomed to exclusion, without water and basic amenities. They serve the city, but the city prefers not to see them.

Also read: Profound insights: Think on these things