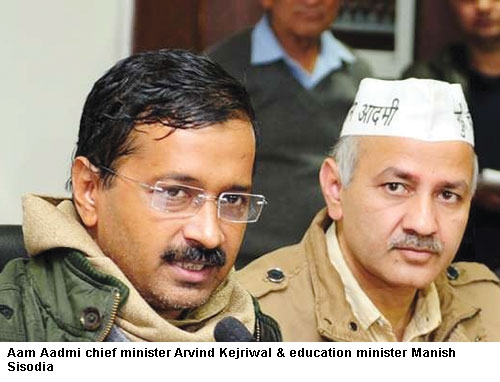

There’s a virtual unanimity among political pundits and educationists that no political party countrywide is as committed to improving and upgrading K-12 public education as the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), which has an overwhelming majority (67 out of 70 seats) in the Delhi state legislative assembly. Despite this huge majority, the AAP government has not been given sufficient elbow room by the BJP/NDA Central government, to rule Delhi state since 2015 when shortly after the BJP/NDA coalition swept General Election 2014, it trounced the BJP in the Delhi legislative assembly election.

There’s a virtual unanimity among political pundits and educationists that no political party countrywide is as committed to improving and upgrading K-12 public education as the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), which has an overwhelming majority (67 out of 70 seats) in the Delhi state legislative assembly. Despite this huge majority, the AAP government has not been given sufficient elbow room by the BJP/NDA Central government, to rule Delhi state since 2015 when shortly after the BJP/NDA coalition swept General Election 2014, it trounced the BJP in the Delhi legislative assembly election.

Prompted by the AAP state government, the Delhi Commission for Protection of Child Rights (DCPCR), established under s.31 of the Right of Children to Free & Compulsory Education (RTE) Act, 2009, is all set to publish a first-ever evaluation report of 5,800 schools in Delhi. In this report all schools will be graded on a 1-4 scale on three broad parameters: safety and security; teaching and learning; community participation and social integration.

The DCPCR evaluation report ran into headwinds as soon as the school surveys began. Municipal corporations controlled by the BJP refused to cooperate. Though they have relented, another controversy has been sparked by allegations that budget private schools are not adhering to s.12 (1) (c) of the RTE Act which makes it mandatory for all private schools to reserve 25 percent of capacity in classes I-VIII for children from poor households in their neighbourhood.

This controversy flared up after DCPCR member Anurag Kundu alleged that private schools regulated by the Delhi state government have a “fill rate” of 76 percent under s.12 (1) (c) whereas schools regulated by municipal corporations controlled by the BJP have a fill rate of less than 20 percent. In support, Kundu cited a report of the Delhi-based NGO Indus Action prepared in association with IIM-Ahmedabad and PVR Nest, which assessed the s.12 (1) (c) compliance records of private schools in the national capital.

However, R.C. Jain, president, State Public Schools Management Association, Delhi, contends that the Indus Action initiative is a politically biased exercise. “There is a political agenda behind this. While conducting the survey, they are collecting data about children from economically weaker sections, interviewing teachers and parents to show the Delhi state government in better light. The state government hasn’t sent any children to our private budget schools for admission under s.12 (1) (c). Therefore, obviously our fill rate will be low,” says Jain.

The Indus Action report titled The Bright Spots, published just before yet another anniversary (April 1) of the landmark RTE Act and General Election 2019, says that nationwide there is a slowdown in admissions under s.12 (1) (c), from 2.27 million in 2015-16 to 2.18 million in 2016-17. Moreover the number of private schools admitting poor children from their neighbourhood had declined from 60,000 in 2015-16 to 46,000 in 2016-17.

The constitutional validity of s.12 (1) (c), which mandates that all private schools should reserve 25 percent of capacity in class I for poor children from neighbourhood households free-of-charge and retain them up to class VIII, recovering part of the cost of education provision from state governments, was tested in the Supreme Court ab initio. In Unaided Schools of Rajasthan vs. Union of India (2012), the apex court upheld the Act but exempted minority (and boarding) schools from the ambit of s.12 (1) (c).

According to the Indus Action report, since then the number of minority schools countrywide more than doubled and 10,000 minority schools were promoted in 2016-17. Moreover, under pressure from private school promoters, several state governments including Uttar Pradesh and Karnataka have diluted s.12 (1) (c) by stipulating that private schools are obliged to admit poor children only if there are no government schools in their neighbourhood.

“Nearly half of the 200 million households in the country have a child eligible for free-of-charge admission into private schools in their neighbourhood. Expenditure on schooling constitutes a significant share of all households. As citizens, we should ask our political leaders and legislators to enforce the RTE Act and s.12 (1) (c) in particular in the interests of social inclusion and harmony,” says Prof. Ankur Sarin, faculty, public services group, IIM-Ahmedabad.

Curiously, the attention of the Indian academy and intellectuals seems to be focused on implementation of the RTE Act which discriminates against private budget school promoters and enforcing s.12 (1) (c) in particular. They seem relatively unconcerned about raising teaching-learning standards in government schools which will dampen the demand from EWS (economically weaker section) households for admission into private schools. In the circumstances, the strategy of Delhi’s AAP government to raise teaching-learning standards in government schools to surpass low-ranked private schools is as exceptional as it is commendable.

Autar Nehru (Delhi)