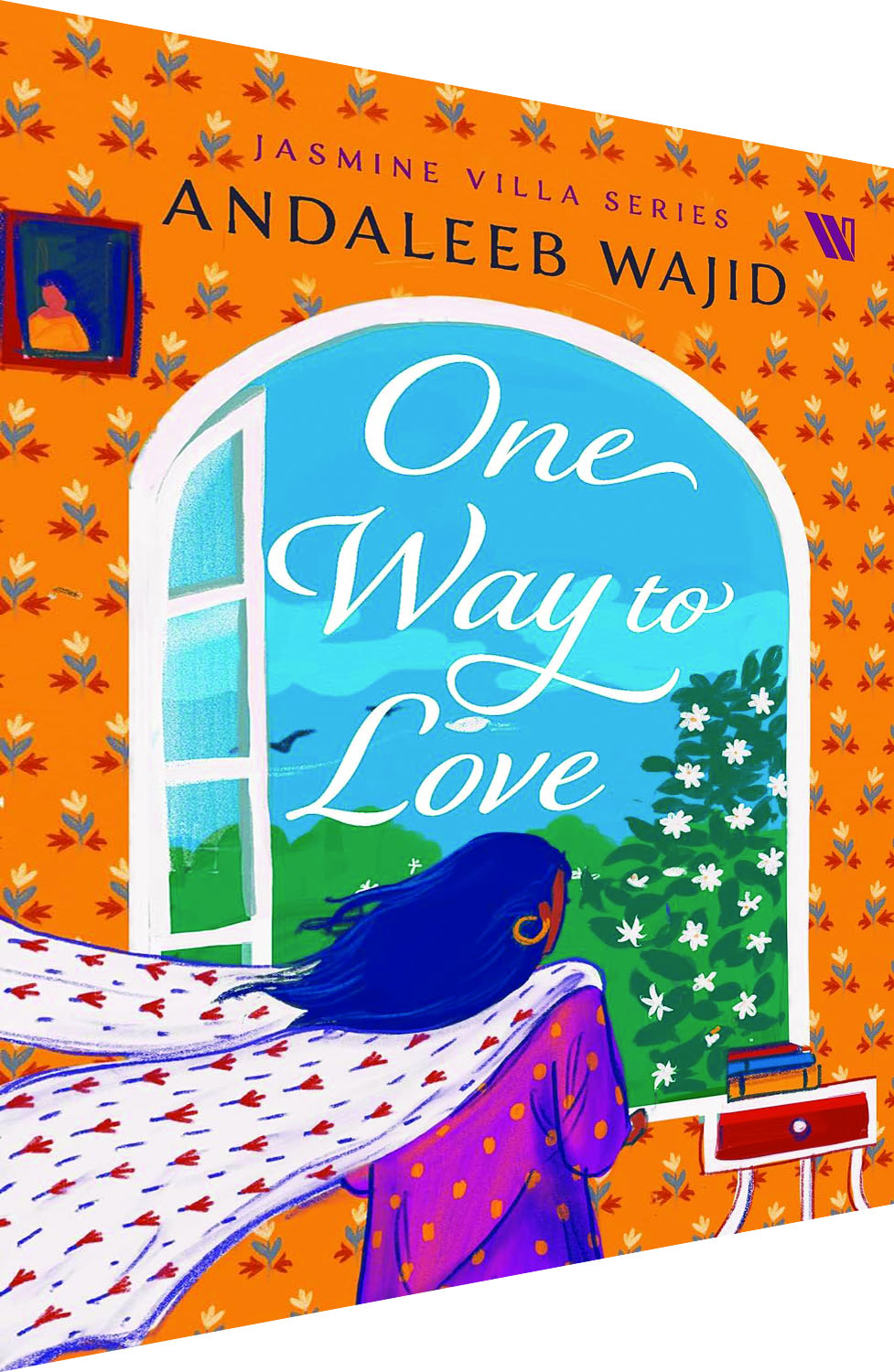

ONE WAY TO LOVE ; LOVING YOU TWICE; THREE TIMES LUCKY (Jasmine Villa Series)

ONE WAY TO LOVE ; LOVING YOU TWICE; THREE TIMES LUCKY (Jasmine Villa Series)

Andaleeb Wajid

westland publications

Rs.399

Pages 276; 296 & 290

Romance stories written by Muslim women published in women’s magazines enjoy phenomenal popularity among Urdu readers

Andaleeb Wajid, a young Bangalore-based, hijab-wearing woman, who has written over 40 novels in genres ranging from young adult and romance to horror, often raises eyebrows because her overtly Muslim identity is seen to be in contradiction with her choice of the genre derisively termed ‘chick lit’. Is a hijab-clad Muslim woman reading and writing romances an anomaly?

Actually, not! And those familiar with the tradition of women writing in Urdu, for instance, novels by Hijab Imtiyaz Ali and Sughra Humayun Mirza, or short stories published in women’s magazines and periodicals, know the phenomenal popularity of romances among Urdu readers. In fact, romance was one of the most popular genres in the late 19th and early 20th century in Urdu women’s magazines and periodicals whose Muslim women readers eagerly consumed it.

The three books under review, which together constitute the Jasmine Villa series, broadly fall within this category. All novels are dedicated to one sister in a family of three sisters, their romantic encounters and trysts with the issues of romance and marriage.

Jasmine Villa is the home of Tehzeeb, Ana, and Athiya who live with their father Yusuf Hasan. A man of faith, Yusuf has raised his three daughters after the death of their mother, given them good education and freedom. Though temperamentally different, all three sisters share a strong bond and exude confidence, pride, and self-respect.

Within this context, the three novels move in different directions as they follow the diverse romantic trajectories of the three sisters. Each sister experiences love in her own way and on finding her prince charming, encounters the complex social contexts in which their love stories unfold. Faced with the challenge of breaking the norms set by their father, they exhibit resolute spirit.

The first book in the series follows the story of the eldest, Tehzeeb Hasan. Tehzeeb’s life in her family home she dearly loves is fairly settled. Marriage is not on her mind as she keeps dodging neighbourhood aunties who send her marriage proposals until one day when after Friday prayers, her father meets his old friend Bakhtiyar Ahmed in a mosque and the friend asks for her hand in marriage to his only son. Tehzeeb’s father agrees and asks her to meet the boy. Young and handsome Ayub Ahmed, too, has no desire for matrimony and is taken aback by his father’s decision. However, when the two meet, it’s love at first sight and smitten by each other, they decide to marry.

With this begins Tehzeeb’s struggle with a new life, new role in a new family, rituals, societal expectations and class asymmetries. Called upon to discharge the role of the perfect bahu, the free-spirited Tehzeeb feels stifled and trapped in an endless round of inane parties and senseless dressing. The novel captures Tehzeeb’s intrepid struggle to hold on to her own identity amidst the women of her husband’s household. Ayub’s unconditional love helps her overcome their many differences. It is the strength of her husband’s love that finally persuades her to return to him.

The second book follows the story of Ana, the second sibling, a reserved and self-possessed young girl. Unlike elder sister Tehzeeb, Ana prefers to keep her emotions to herself. She meets Luqman, Ayub’s friend, at Tehzeeb’s wedding in the first book and there’s mutual attraction. However, their romance takes off in the second book when on finding herself seated next to Luqman during a long flight, Ana feels her control over her emotions slipping. Vexed at this change, she regrets meeting him. Luqman, a handsome young man with a lucrative job is much sought after by young women, so Ana refuses to admit her feelings for him. The story moves through many twists and turns and misunderstandings. She accepts her father’s wish to marry the young man whose proposal they have received, only to discover later that the boy in question is Luqman’s elder brother Farhan. In all, Loving You Twice is a heady mix of romance, passion, heartbreak, and suspense.

Three Times Lucky introduces Athiya, the youngest, and most impetuous of the three Hasan sisters. Unlike the other two, Athiya doesn’t regard the institution of marriage as a source of bliss. Her life takes a turn when she accepts Farhan Ahmed’s offer of work at his office. Farhan is besotted with Athiya and when she gets into trouble after recklessly accepting an assignment, he is there to save her, except that Athiya is disinclined to accept any favours from him. It is through the intervention of friends and siblings that the young lovers realise the power of love. All three novels, thus, fulfill the objective of pursuit of happiness, through which they create emotional resonance within the reader.

Wajid’s romances don’t weave a fairy tale aura that is removed from social reality. On the contrary, all her characters live and breathe the same air as any urban middle-class Muslim woman of their milieu, that is, the conservative world of south Indian Muslim families of Bengaluru. Wajid’s plots do not take recourse to the extraordinary or unusual to hook the reader’s interest. Though all three novels retain a light tone, are fast paced and intense, with intimate experiences usually associated with chick lit, they demonstrate a complexity that we don’t usually associate with novels written for young women.

Wajid refrains from offering her readers escapist fantasies of female autonomy or uncomplicated happy endings. The seeming absence of a dense web of contextualisation such as cultural and political issues in Wajid’s books is offset by their ethnographic significance, and their entanglement in the intricate politics of religion, gender, and class. It’s time academia and critics shed their bias for literature with capital L and take note of writings that articulate concerns of young girls and tell about their lives and choices.

Nishat Zaidi

(The Book Review)