Phil Cotton, vice chancellor of the University of Rwanda, often has to say “no” to well-meaning potential benefactors. “Lots of academic colleagues want to send me stuff they don’t need — old textbooks or out-of-date medical equipment that will last only a short time,” explains Cotton about turning down the offers from leading universities in the West.

Phil Cotton, vice chancellor of the University of Rwanda, often has to say “no” to well-meaning potential benefactors. “Lots of academic colleagues want to send me stuff they don’t need — old textbooks or out-of-date medical equipment that will last only a short time,” explains Cotton about turning down the offers from leading universities in the West.

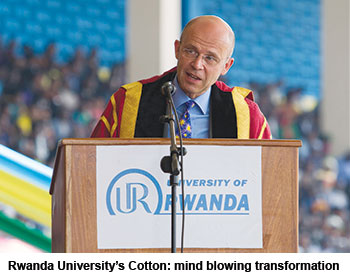

“They think these items aren’t good enough for their students, but they are good enough for mine,” says the London-born former medical practitioner, who has led Rwanda’s only state university since 2015, taking over two years after it was formed in 2013 by a merger of 14 public higher education institutions.

Accepting these gifts can end up costing the university money as electrical equipment often has to be decommissioned and junked at considerable expense when it breaks down, adds Cotton, who joined Rwanda on secondment from the University of Glasgow in 2013 to establish and lead its medical school. However, the challenges of running a new university with ten campuses and 30,000 students could hardly be more different to those faced by Cotton at Glasgow’s medical school, where he is still professor of learning and teaching. “I spend about an hour and a half each day writing to staff and students to congratulate them on various achievements — it might seem a lot, but it’s part of the culture change we need here,” says Cotton, who has also introduced financial rewards to incentivise excellence.

“Every time someone publishes a paper they get $1,000 (Rs.72,105) for their research account,” explains Cotton, who says this is more than the $800 that senior professors will take home each month in Rwanda. Some 177 academics are also being supported to take a Ph D, since less than 25 percent of the university’s 1,400 academics currently have a doctorate. “The problem is that as soon as they graduate, they are mopped up by private education providers,” says Cotton.

Despite frustrations with some of Rwanda’s more archaic university regulations (quality inspectors take a keen interest in the number of library books and lecture theatre seats), Cotton says he remains a strong supporter of President Paul Kagame, especially his focus on improving educational opportunities in this East African country, still mainly known for the 100-day genocide in 1994 in which up to 1 million Tutsis were massacred.

“There is a vision of national transformation through higher education that is mind-blowing because it involves a complete obsession with helping every single young person in Rwanda,” says Cotton, who credits President Kagame’s “energy for moving the country forward”.

With primary school attendance at nearly 100 percent — the highest rate in Africa — attention is now turning to how this country of 12.5 million people can improve secondary and tertiary education. Rwanda’s flagship university is not only a crucial part of the country’s ambitions to become a developed knowledge economy, it is also playing its part to ensure that no catastrophic rift between ethnic groups ever happens again, says Cotton, who points to the huge amount of voluntary work done by students. “On the last Sunday of every month, everyone does community work, such as litter picking, together — it’s very important for community cohesion and it’s also why Kigali is one of the tidiest cities in the world,” he says.