Bristling with a gamut of discretionary rules, regulations and conditions, the UGC (Setting up and Operation of Campuses of Foreign Higher Educational Institutions in India) Regulations, 2023, is unlikely to enthuse top-ranked foreign universities to establish owned campuses in India – writes Summiya Yasmeen

Top-ranked Anglosphere universities: unlikely contenders

Seventeen years after the National Knowledge Commission headed by US-based billionaire technocrat Sam Pitroda first recommended the entry of foreign higher education institutions (FHEIs) into India, the BJP government at the Centre has given the formal greenlight for them to establish campuses on Indian terra firma.

On November 7, the Delhi-based University Grants Commission (UGC) notified the UGC (Setting up and Operation of Campuses of Foreign Higher Educational Institutions in India) Regulations, 2023, providing a legal and regulatory framework for foreign universities to establish owned campuses in India. According to Prof. Jagadesh Kumar, UGC chairman, the regulations will “facilitate the entry of FHEIs into India in line with the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 recommendations and provide an international dimension to higher education in India”.

However, not many in Indian academia — or in the head offices of universities abroad — are enthused by the regulations. After initial euphoria of foreign universities having been permitted to establish sprawling new campuses with their trademark superior infrastructure in India, there’s growing awareness that the conditions and regulations fine print is less than inviting. UGC’s five-page notification setting out the terms and conditions for entry of FHEIs which enjoy real autonomy back home, bristles with a gamut of discretionary rules and regulations that are likely to put off their management boards.

For a start, every applicant foreign university should be ranked among the global Top 500 by agencies approved by UGC “from time to time”. Next, the applicant foreign university must give an undertaking that the degrees/qualifications it awards are “at par with that of the main campus in the country of origin” and that “the qualifications awarded to the students in the Indian campus shall be recognised and treated as equivalent to the corresponding qualifications awarded by the FHEI in the main campus located in the country of origin for all purposes, including higher education and employment”.

There are other stringent conditions imposed upon FHEIs thinking of tapping into the world’s largest higher education market. The fees structure should be “transparent and reasonable”; “the qualifications of the faculty appointed shall be at par with the main campus of the country of origin” and the FHEI “shall ensure that the foreign faculty appointed to teach at the Indian campus shall stay at the campus in India for a reasonable period” and that licensed FHEIs “shall not offer any such programme of study which jeopardises the national interest of India or standards of higher education in India” or are “contrary to the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, decency, or morality”. Another provision states the FHEIs need prior approval of UGC before starting any new programme. Moreover, the commission has awarded itself the power to visit FHEI campuses to “examine its operations to ascertain the infrastructure, academic programmes and overall quality and suitability”. (see box p.84)

The presumption of UGC (and BJP government at the Centre) seems to be that FHEIs including top-ranked universities are desperate to establish campuses in India and will be ready to comply with stifling discretionary regulations drawn up by the educracy. However, in the past 12 months since the BJP government at the Centre announced — decision to allow FHEIs into India and UGC released draft regulations for public feedback, only two foreign universities have agreed to establish campuses in India — Deakin and Wollongong universities (both Australian and ranked #233 and #162 respectively in the QS World University Rankings 2024). None of the Top 100 FHEIs of the UK, US or Canada — the favourite foreign study destinations of Indian students — has expressed interest. Now with the stringent UGC regulations notified, any resolution to plant their flags in India is likely to run awry.

Commenting on the new UGC regulations, public intellectual Dr. Pratap Bhanu Mehta, an alum of the blue-chip Oxford (UK) and Princeton (US) universities and former president of the Delhi-based Centre for Public Policy Research, Delhi, says “if we think universities can flourish without academic freedom, we have our heads in the sand”. According to Mehta, the government’s higher education reforms are based on several false premises.

Commenting on s.6 of the UGC regulations which require FHEIs to ensure qualifications of the faculty posted in India will be on a par with faculty in the parent institution, Mehta says that the word “qualification” is open to interpretation. “If it simply means formal equivalence of qualifications (Ph D from a good institution, etc.), then most institutions are on a par. But if it means faculty who are exceptional (which is what the top institutions claim they have), there is no cost advantage to moving to India. Land and capital costs are not cheap here. But if you are going to define equivalence as something close to those who have been through the tenure processes of top-ranked universities, they have no economic or lifestyle incentives to spend a lot of time in India unless either their salaries are matched or exceeded. This makes running campuses in India with the same “standard” prohibitively expensive,” says Mehta, former vice chancellor of the top-ranked private Ashoka University, Sonipat, who resigned in 2021 after it became “abundantly clear” to him that his forthright public essays had become a “political liability” for the institution.

Moreover, there’s the question of “regulatory trust,” says Mehta in his weekly long form op-ed essay (January 9, 2023) in the Indian Express written before the UGC regulations were notified. More pertinently, Mehta highlights that the reason almost none of the top Ivy League institutions such as Harvard, Yale, and Princeton have branch campuses abroad is because the “economics and the structural form of a top research university makes it difficult to reproduce them.”

Bhanu Mehta: freedom prerequisite

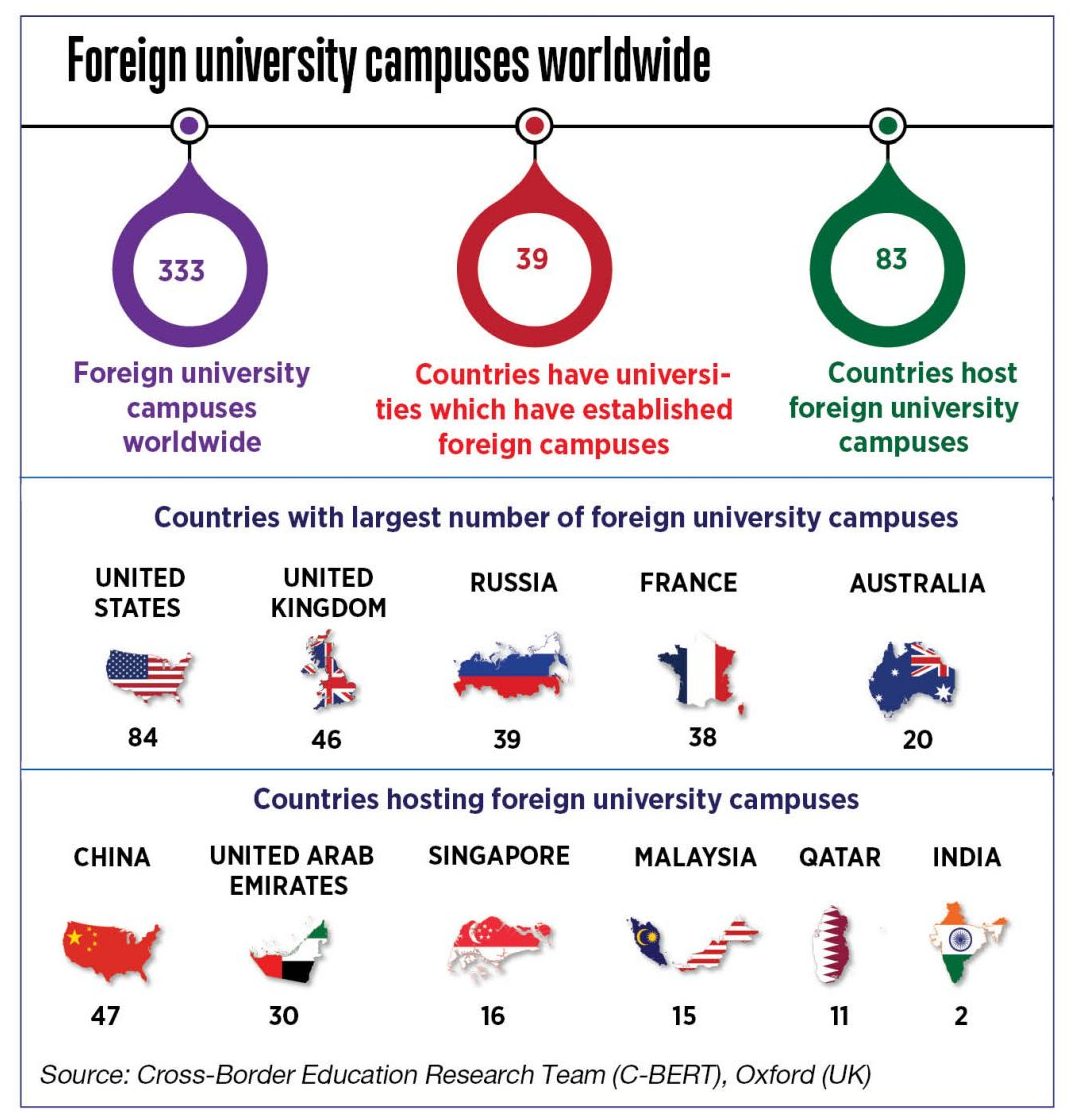

Recent research of the Oxford (UK)-based Cross-Border Education Research Team (C-BERT) reveals that as of March, 2023, 83 countries have “imported” FHEIs (333 campuses overall), of which the largest number are in China (47), UAE (30), Singapore (16), Malaysia (15) and Qatar (11). In China, barring NYU Shanghai, none of the foreign university campuses is of top-ranked universities. They are either joint centres (such as Tsinghua-UC Berkeley Shenzhen Institute, University of Michigan-Shanghai Jiao Tong University Joint Institute) or universities set up in collaboration with existing Chinese universities (for example, Duke-Kunshan University). Ditto in Malaysia, not one foreign university is ranked among the global Top 100 universities (see box p. 82). Significantly, the majority receive some form of subsidy from the host government.

Indeed, countries such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Qatar not only provide liberal regulatory environments for foreign universities but also land grants, tax breaks, and financial assistance. For instance, New York University’s branch campus in Dubai is entirely financed by the UAE government. Therefore, UGC’s presumption that foreign universities are waiting to gatecrash India, which instead of incentives offers a plethora of regulations and code of conduct rules, is likely to prove wishful thinking.

Raj Kumar: collaboration alternative

“Universities around the world function as autonomous institutions with minimal interference from governments. These days, the onus is on host countries to create attractive and enabling ecosystems for world-class universities to set up campuses in their countries. In some cases, host countries provide land and funding to foreign varsities,” says Dr. C. Raj Kumar, vice chancellor of the private top-ranked O.P. Jindal Global University (JGU), Sonipat (Haryana).

According to Prof. Raj Kumar, rather than establishing bricks-n-mortar campuses the current trend is for globally top-ranked universities to contract international collaboration agreements for student and faculty exchange and joint degree and research programmes. “My humble suggestion is that we should focus on how Indian universities can collaborate with leading international universities. This will not only help us to fulfil the vision of NEP 2020, but also create extraordinary opportunities for students and faculty in India to engage with leading universities of the world. The capital-intensive campuses investment model envisaged by UGC will not work in India and runs the risk of making higher education highly inaccessible and non-inclusive,” Dr. Raj Kumar, a polymath alum of Madras, Delhi, Oxford and Harvard universities and founder VC of JGU told EducationWorld (December 2023).

However, spokespersons of Deakin University, Australia — the first foreign university to establish a campus in the Gujarat International Finance Tec-City (GIFT City) — are “confident about the execution and delivery of the GIFT City campus and the success of making international standards of education delivery possible for students.” While declining to comment on the UGC Regulations 2023, Ravneet Pawha, Vice President (Global Alliances) and CEO, Deakin University (South Asia), says that “Deakin’s India campus is first and foremost a momentous achievement of bilateral knowledge collaboration between Australia and India”.

Pawha is unfazed by the latest UGC regulations and code of conduct firman. “Deakin University was the first foreign university to set up operations in India way back in 1994 and over the past three decades, we have forged meaningful partnerships with academia, industry, and government. Establishing our own campus is the logical next step for Deakin to deliver international classrooms for students in India. We thank government agencies in the education ecosystem of both countries as well as the prime ministerial committees for deepening our engagement with India. The university is establishing India’s first international university branch campus in accordance with prescribed guidelines and compliance norms. Deakin will provide the same standard of higher education in GIFT City as at Deakin, Australia, as accredited by TEQSA (Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency),” says Pahwa.

Deakin University, GIFT City, Gujarat.

Ravneet Pahwa

The Deakin India campus is all set to be inaugurated in GIFT City, Gujarat on January 10 with commencement of two-year Masters’ programmes in Business Analytics and Cyber Security (Professional) priced at Rs.21.4 lakh for two years. However, it’s pertinent to note that Deakin’s strategic location in GIFT City — a government-sponsored special economic zone — offers its numerous advantages including tax breaks, freedom to charge fees in international currency and full repatriation of profit.

Although several Asian countries including Communist China permitted Anglosphere universities to establish outpost campuses decades ago, successive governments in New Delhi committed to self-reliance, dithered over the issue.

But with any of India’s 42,000 undergrad colleges and 1,126 universities conspicuously absent in the annual global Top 200 league tables of QS and THE — the well-reputed London-based higher ed institutions ranking agencies — and an ever-increasing outflow of school-leavers and graduates to universities abroad assuming flood-like proportions, in 2006, the Congress-led UPA-I government established the National Knowledge Commission headed by US-based billionaire technocrat Sam Pitroda. The commission recommended facilitating the entry of foreign universities into the country. The following year, the Foreign Higher Educational Institutions (Regulations of Entry, Operation of Quality and Prevention of Commercialisation) Bill, 2007, was presented in Parliament. But at the last moment, the Bill was scuttled by leftie Congress party HRD (education) minister Arjun Singh.

Again in 2010, after the Congress-led UPA-II government was voted to power at the Centre for a second term, a revised Foreign Educational Institutions (Regulation of Entry and Operations) Bill, 2010 was tabled in Parliament. But it was vehemently opposed by the BJP and communist parties leading to a stalemate, and eventually killed.

In 2014, after the BJP won a landslide victory in the General Election, the issue of foreign universities coming to India was put in deep freeze with the right-wing Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), ideological mentor of the BJP, strongly opposing the idea of “westernizing” Indian education. However, with Indian universities still languishing in the nether reaches of the QS and THE global rankings and the outflow of students to foreign shores increasing, in its second term (2019), the BJP government did an about turn and reversed its position on this issue.

The National Education Policy (NEP) approved by the Union Cabinet on July 29, 2020 strongly endorsed the entry of foreign universities into the country. “High performing Indian universities will be encouraged to set up campuses in other countries, and similarly, selected universities e.g, those from among the Top 100 universities in the world will be facilitated to operate in India. A legislative framework facilitating such entry will be put in place, and such universities will be given special dispensation regarding regulatory, governance, and content norms on par with other autonomous institutions of India,” says NEP 2020.

With the BJP committed to implementation of this provision of NEP 2020, the Modi government set about preparing the “legislative framework” to facilitate this recommendation. However, given the history of several foreign universities Bills presented in Parliament, this time round the BJP government opted to take the route of a notification under ss.12 and 26 of the University Grants Commission Act, 1956.

Kumar: other considerations

NEP 2020’s stated goal of internationalisation of Indian higher education apart, another major factor which prompted the U-turn of the BJP government is the ever-rising number of Indian students emplaning for higher education abroad. According to Union education ministry data, an estimated 770,000 Indian students enrolled in foreign universities in 2022 — a 68 percent rise over the previous year. Currently, an estimated 1.3 million Indian students are pursuing study programmes in 78 countries worldwide. Their annual expenditure abroad is $47 billion (Rs.3.9 lakh crore) — several multiples of the total Union budget allocation for education (Rs.1.12 lakh crore) in 2023-24. It is this consideration that a large — and ever-rising — number of school-leavers and graduates are hell-bent on acquiring foreign qualifications and that the overwhelming majority of them never come back, and on the reasoning that the mountain must be brought to Mohammed, the BJP government has greenlighted the entry of foreign universities into India.

However, expert opinion on whether this initiative will stem the outflow of Indian students to offshore institutions is divided. An analysis of the C-BERT database indicates that not only are top-ranked FHEIs not enamoured with the idea of establishing campuses abroad, most foreign varsity campuses proposed are very small, with an average enrolment of 300-400 students. Therefore, even after assuming that foreign universities will overlook the onerous regulatory pre-conditions to establish campuses in India, the supply by way of number of seats would still be very limited. Moreover, students have other considerations in mind for venturing to study abroad.

“Admittedly, the UGC regulations for setting up and operating FHEIs in India will provide more options for students and raise standards in higher education. However, their effectiveness in stemming the flow of students abroad is likely to be limited. This is because students planning to study abroad not only look for world-class education but also for international exposure, multicultural environment, and post-study work opportunities. Indian students choosing foreign universities are looking for a comprehensive educational experience rather than merely acquiring an international degree. Foreign universities offer multicultural classrooms, unique academic and lifestyle freedoms and post-study work visas allow students to gain valuable international work experience. Moreover, I think getting foreign universities to set up campuses in India is a long-haul endeavour. While the move has enthused some foreign universities, attracting top-ranked institutions to establish campuses in India will require time and sustained effort,” says Piyush Kumar, regional director, South Asia and Mauritius of IDP Education, which offers foreign education consultancy services to students in over 30 countries.

“Admittedly, the UGC regulations for setting up and operating FHEIs in India will provide more options for students and raise standards in higher education. However, their effectiveness in stemming the flow of students abroad is likely to be limited. This is because students planning to study abroad not only look for world-class education but also for international exposure, multicultural environment, and post-study work opportunities. Indian students choosing foreign universities are looking for a comprehensive educational experience rather than merely acquiring an international degree. Foreign universities offer multicultural classrooms, unique academic and lifestyle freedoms and post-study work visas allow students to gain valuable international work experience. Moreover, I think getting foreign universities to set up campuses in India is a long-haul endeavour. While the move has enthused some foreign universities, attracting top-ranked institutions to establish campuses in India will require time and sustained effort,” says Piyush Kumar, regional director, South Asia and Mauritius of IDP Education, which offers foreign education consultancy services to students in over 30 countries.

Although inviting foreign universities to establish owned campuses in India may partially stem the outflow of school-leavers and college grads fleeing abroad for superior higher education and respected qualifications, it raises the question of why indigenous scholars are ready to pay vast amounts for foreign education and qualifications.

The plain truth is that the Central and state governments and the country’s ubiquitous educracy have failed to upgrade and modernise India’s moribund 42,000 colleges and 1,126 universities. With the exception of a few Central government-funded institutions such as the IITs, IIMs and Delhi University and a handful of private universities, the majority of the country’s HEIs are mediocre institutions plagued with infrastructure and faculty shortages and provide unfulfilling higher education not respected by India Inc and government which run their own job entrance exams. As alluded earlier, even the best struggle to make it into the Top 200 of QS and Times Higher Education global rankings.

Moreover while more affordable than studying abroad, tuition fees levied by branch campuses of FHEIs are likely to be several multiples of those charged by Indian HEIs rendering FHEI branch campuses ‘ elitist’. Their major contribution is likely to be by way of raising standards and setting new benchmarks in higher education — a long-term benefit. The UGC regulations which permit the entry of FHEIs into India is no substitute for the long-term and onerous task of upgrading and reforming India’s 42,000 colleges and 1,126 universities.

Bhatt: welcome safeguards

Meanwhile even though the dominant opinion within the academy is that the UGC Regulations 2023 are unlikely to enthuse the world’s best FHEIs, some academics welcome them. “The UGC Regulations are in line with NEP 2020 recommendations to establish a legal and regulatory framework for FHEIs operating campuses in India. During the initial phase, clear standard operating procedures are needed to establish a robust framework for foreign universities establishing campuses in India, and to prevent sub-par and fraudulent institutions from exploiting Indian students. I would also suggest that initially, it would be advisable to have an Indian representative preferably from the government on the Board of Governors of the Indian campuses of FHEIs. With the passage of time after the initial problems are ironed out, government could withdraw from the boards,” suggests Prof. Geeta Bhatt, director of the Non-Collegiate Women’s Education Board, Delhi University.

While academics such as Dr. Geeta Bhatt welcome foreign universities with conditions, Left academics are wholly opposed to their entry. They contend that this initiative will exacerbate inequalities in Indian education, and more important, graft western, alien cultural consciousness on to our higher education institutions.

APU’s Dhankar (centre): alien cultural consciousness

“Every nation has its own distinctive cultural consciousness and world-view. India’s deepest thinkers and intellectuals Sri Aurobindo and Rabindranath Tagore envisioned the university as a deep well and centre of history and culture rooted in the Indian context from which knowledge, ideas and innovations relating to teaching the social sciences, art and literature in particular, would emerge. The entry of foreign universities will provide further impetus to the process of grafting alien cultural-consciousness and world-view on to our higher education institutions. This process which began during the British Raj remained uncorrected after independence. As a result, our higher education system has failed miserably and our cultural consciousness has substantially diminished, force-fitted into social theories developed to understand a different cultural milieu. A large number of foreign, especially British schools and universities, setting standards and benchmarks in Indian education will result in completion of Lord Macaulay’s agenda of transforming middle class Indians into second class Englishmen, resulting in schizophrenic moral codes and jingoistic nationalism for self-assertion,” Rohit Dhankar, professor at the Azim Premji University, Bengaluru (estb.2010), ranked India’s #1 private university for social sciences in the EW India Higher Education Rankings 2022-2023, told EducationWorld (February 2023) after the draft UGC regulations for the entry of foreign universities were released for public comment.

Thakkar: red tape apprehension

This isolationist mindset is pervasive in government and educracy as indicated by the wide discretionary regulatory powers UGC has conferred upon itself to monitor and regulate FHEI campuses in India. “I am not surprised that only two foreign universities have stepped forward to set up campuses in India — that too in GIFT City, which is a special economic zone providing special concessions to foreign investors. The plain truth is that our higher education system is over-controlled by government. Even the country’s showpiece IITs and IIMs have hardly any autonomy. For example, if an IIT wants to purchase lab equipment valued at Rs.10 lakh, it has to wait 11 months for ministry approval. A foreign university is unlikely to risk its money or reputation in such an uncertain and discretionary regulatory environment. Moreover why can’t all the freedoms promised to foreign universities to design their syllabuses and curriculums, and determine tuition fees also be granted to Indian public and private universities, to create a level playing field?” queries a former IIT professor who preferred to remain anonymous.

With the new UGC regulations for FHEI entry into India imposing a plethora of rules, regulations and code of conduct upon them, few if any, are likely to replicate the sprawling capital-intensive campuses of back home in India. The preferred route of entry is likely to be through privileged economic zones such as GIFT City or by way of partnerships with local universities/edupreneurs to export intellectual property and know-how. This model is already working well in K-12 education. Over the past quinquennium, several globally respected foreign school brands including Harrow, Wellington, and Shrewsbury — all based in the UK — have entered into partnerships with experienced local education groups who provide land, buildings and infrastructure.

Last September, Harrow School (estb.1572) inaugurated its first India co-ed day-cum-boarding campus in Bengaluru in partnership with the Amity Group. Likewise, Wellington College, another venerable British boarding school (estb.1853), inaugurated a day-cum-boarding campus in Pune on September 14, in partnership with the Dehradun-based Unison Group. The preferred partnership model is for the Indian partner to establish the campus and secure all regulatory clearances, while the foreign partner contributes the brand name and intellectual capital. The general expectation is that foreign universities will take a similar minimal investment route to enter India.

“The BJP government’s decision to allow foreign universities to establish physical campuses in India is a good start and indicative of its intent to liberalise the higher education sector. However, the UGC Regulations are not very encouraging. Most foreign universities and top-tier institutions in particular will wait and watch before risking investment in capital-intensive campuses. They will most likely sign asset light collaboration agreements with domestic Indian edupreneurs and export intellectual property,” says Atul Thakkar, Mumbai-based Director of Anand Rathi Investment Banking and head of its education, education allied services and technology sector.

Thakkar believes the success of the government’s foreign universities in India initiative will depend on its will to liberate Indian higher education. “The onus is on government to create a facilitative environment for foreign universities to operate in India. Not just for foreign universities, the government needs to deregulate higher education for Indian edupreneurs. There is no shortage of domestic edupreneurs ready and willing to invest in this sector provided it’s freed from red tape. Indian edupreneurs are capable of setting up world-class universities on a par with the best globally,” adds Thakkar.

Against the backdrop of the half-hearted UGC rules and regulations inviting FHEIs to establish back-home style campuses in India, the silver lining is NEP 2020 which unambiguously encourages internationalisation of higher education and mandates government to facilitate foreign universities to establish campuses in India and vice versa. Even modest success of this foreign universities initiative requires UGC to loosen its regulatory grip and create inviting ground conditions to attract the world’s best foreign universities. For foreign, especially Anglosphere universities, institutional autonomy is a live and serious issue. India’s ubiquitous educracy needs to learn to respect this concept

UGC FHEI entry regulations 2023

On November 7, the apex Delhi-based University Grants Commission (UGC) notified the UGC (Setting up and Operation of Campuses of Foreign Higher Educational Institutions in India) Regulations, 2023. The five-page notification set outs the terms and conditions for FHEIs to operate in the country. Excerpts:

Eligibility

(1) The Foreign Higher Educational Institution (FHEI) intending to establish campuses in India shall fulfil any of the following criteria at the time of application, that:

(a) it should have secured a position within the Top 500 in the overall category of global rankings at the time of application, as decided by the Commission from time to time; or

(b) it should have secured a position within the Top 500 in the subject-wise category of global rankings at the time of application or should possess outstanding expertise in a particular area, as decided by the Commission from time to time.

(2) In the case of two or more than two FHEIs intending to collaborate to establish campuses in India, each FHEI should meet the eligibility criteria

Procedure for approval

(3) The FHEI shall upload the following documents along with the application on the UGC portal, namely:

(a) permission by the Governing Body or Board, by whatever name called, for establishing campuses in India;

(b) information on the proposed location, infrastructural facilities, fee structure, academic programmes, courses, curricula, availability of faculty and financial resources for setting up and operations of campuses in India, and any other details that may be sought;

(c) an undertaking to the effect that the quality of education imparted by it in its Indian campus is similar to that of the main campus in the country of origin; and the qualifications awarded to the students in the Indian campus shall enjoy the same recognition and status as if they were conducted in its home jurisdiction, that is, they shall be recognized in the country of origin of the FHEI and shall be equivalent to the corresponding qualifications awarded by the FHEI in the main campus located in the country of origin.

(d) the latest Accreditation or Quality Assurance report from a recognized Body; and

(e) any other document as specified in the application portal.

Admission and fees structure

(1) The campus of FHEI may evolve its admission process and criteria to admit domestic and international students.

(2) The FHEI shall decide the fee structure, which shall be transparent and reasonable.

(3) The FHEI shall make available the prospectus on its website at least sixty days before the commencement of admissions, including fee structure, refund policy, number of seats in a programme, eligibility qualifications, and admission process.

(4) Based on an evaluation process, the FHEI may provide full or partial merit-based or need-based scholarships from funds such as endowment funds, alumni donations, tuition revenues and other sources.

(5) The FHEI may give tuition fee concessions to students who are Indian citizens.

Appointment of faculty and staff

(1) The FHEI shall have the autonomy to recruit faculty and staff from India and abroad as per its recruitment norms.

(2) The FHEI may decide the qualifications, salary structure, and other conditions of service for appointing faculty and staff. However, the FHEI shall ensure that the qualifications of the faculty appointed shall be at par with the main campus in the country of origin.

(3) The FHEI shall ensure that the international faculty appointed to teach at the Indian campus shall stay in India for at least a semester.

General conditions

(3) The programme shall not be allowed to be offered in online or in Open and Distance Learning modes. However, lectures in online mode not exceeding ten percent of the programme requirements may be allowed.

(10) The FHEI shall not offer any such programme of study which is contrary to the standards of higher education in India.

(11) The operation of FHEI shall not be contrary to the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency, or morality.

(12) Cross-border movement of funds and maintenance of Foreign Currency Accounts, mode of payments, remittance, repatriation, and sale proceeds, if any, shall be in accordance with the provisions of the Foreign Exchange Management Act, 1999 (42 of 1999) and the rules and regulations made thereunder.

Power to inspect

The Commission shall have the power to visit the campus and examine its operations to ascertain the infrastructure, academic programmes and overall quality and suitability.

(Source: www.ugc.gov.in)